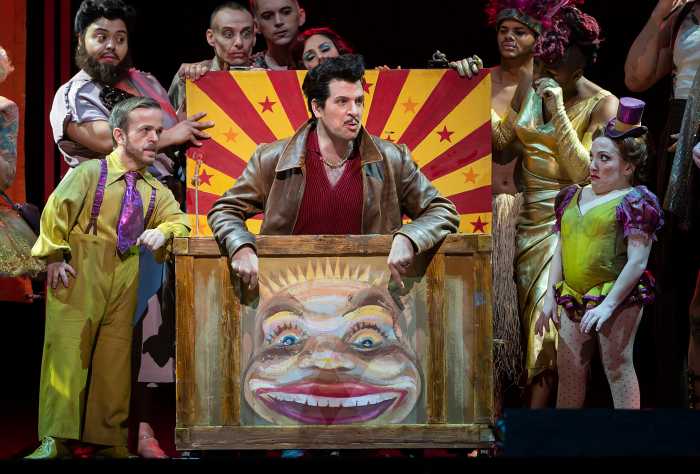

Nathan Gunn and Isabel Leonard in the Santa Fe Opera production of Jennifer Higdon’s “Cold Mountain,” with libretto by Gene Scheer and directed by Leonard Foglia. | KEN HOWARD/ SANTA FE OPERA

Santa Fe Opera, perhaps North America’s most memorably set opera venue, is a joy to visit even when productions vary in quality. A recent stay (August 3-7) started iffily but quickly took on substance and allure.

“La fille du regiment” and “Rigoletto” both utilized junk heap-style sets that made one’s eyes seek out the gorgeous desert and skies for relief. Ned Canty, in his program essay, cited French revolutionary barricades — a strictly urban phenomenon — for Donizetti’s comedy set in rural Swiss Tyrol. Promising to mine “Fille”’s romantic side by restoring dialogue, he instead unleashed a barrage of familiar provincial shtick and “bad television” verbal delivery that sank all but the piece’s best numbers.

Though wise to leave the high-lying parts behind, dynamic tenor Alek Shrader as Tonio sounded in a different vocal league than all his colleagues, with precise, musical phrasing and consistent legato. Anna Christy’s thin soubrette timbre and Chenoweth-style grating dialogue undermined her sincere efforts as Marie. Speranza Scappucci supported capably.

This year’s Santa Fe Opera summer offerings

In “Rigoletto,” Lee Blakely’s direction stumbled often, fostering orgiastic upstaging and rotating visual clutter. Decisions seemed profoundly unmusical and senseless.

Two examples: Rigoletto sings the ravishing “Ah! veglia, o donna” while throttling Giovanna’s neck; Gilda, meanwhile, who responds in the same musical figure, is mystifyingly offstage. Giovanna stole focus for the entire scene.

Later, when the jester reveals to the scoffing courtiers that the “mistress” they have abducted is his daughter, they guffaw — making nonsense of his desperate, “Why don’t you laugh?’

Fortunately, the two superb leads — Quinn Kelsey, a genuine Verdi baritone who welcomely focused on bound legato, not barnstorming, and Georgia Jarman’s lovely Gilda, skilled in staccati — won deserved ovations. Bruce Sledge’s Duke, not especially seductive in manner or timbre, brought skilled musicianship and ease in high tessitura. Peixin Chen (Sparafucile) proved very capable. The Maddalena and Monterone undermined festival standard. Vocal standouts in smaller roles: Jarrett Ott (Marullo) and Michael Adams (Court Usher).

Out composer Jennifer Higdon rose respectably to the daunting challenge of a first opera — moreover, one based on Charles Frazier’s widely read 1997 Civil War epic “Cold Mountain,” already — questionably — filmed. Librettist Gene Scheer and brilliant direction by Leonard Foglia helped substantially, achieving through crosscutting flow what Frazier related in ultra-discursive, stream-of-consciousness style. Higdon’s strength lies in finely textured lyrical orchestration and punctuation. Skirmish scenes sometimes evoked Prokofiev’s dark “Semyon Kotko.” Miguel Harth-Bedoya conducted the respectable if rarely plush festival orchestra tautly.

Higdon clearly relishes vocal ensembles; several scenes suggested an arioso-fueled “Dialogues of the Confederates,” though her vocal lines evoke Barber more than Poulenc. The separated central couple — the deserter Inman (Nathan Gunn) and his quasi-sweetheart Ada back home in North Carolina — often participate in duos, plus a trio and quintet, while physically remote. Words were quite clearly set — and best delivered by two Broadway-caliber actors whose tenors tend to dryness and judder, Roger Honeywell as a strayed, horny clergyman and clarion Jay Hunter Morris as the deserter-hunting Teague. Scheer somewhat conventionalizes this obsessed figure by making him a Jack Rance-style active rival for Ada’s hand — and her farm, which in female solidarity the hardscrabble mountain-bred Ruby has helped her sustain.

Emily Fons excelled as Ruby, wide-ranging, charismatic and moving. Her fellow mezzo Isabel Leonard initially failed to put across Ada’s words, and her “complicated” upper middle timbre limited the effectiveness of soaring lines. Yet Leonard grew in conviction, showing chemistry with Nathan Gunn’s Inman.

Like his male colleagues, Gunn, under pressure, evidenced dry vibrato churn. But softer, less exposed passages were beautifully done and — though scarcely looking less boy-next-door or recognizable as the 1864 “shell” than in recollected pre-war scenes — he gave a serious, compelling performance of a man unwillingly steeped in violence.

Wisely, Scheer deleted nearly all of Frazier’s heavy-handed “Odyssey” references — and re-mixed the identities and qualities of the women Inman encounters on his journey home. This enabled splendid cameo turns by two excellent, individual-timbred mezzos: Chelsea Basler, as a needy single mother, and Deborah Nansteel, as a resourceful runaway slave. Lucinda — merely described in the novel — here has agency and bears witness to an African-American perspective.

Oddly excluded from a New Mexico-premiered opera was Frazier’s poignant evocation of the exploited, expelled Native Americans, whose absence haunts the land — and Inman in particular.

Kevin Burdette — a self-indulgent shtickmeister as “Fille”’s Sulpice — here showed genuine commitment to building two very different characters, a blind seer and Ruby’s wastrel-redeemed-through-music father Stobrod. Though idiomatic, Higdon’s rendering of his fiddling proved less than magical; tweaking is needed. Ending an epic’s tough; some re-sorting may alleviate a sense of distension. A chilling, powerful choral scene reviving all the characters flirted with finale-hood, but then interpersonal dynamics re-commenced, leading both to closure and tragedy.

A brief postwar epilogue, while faithful to Frazier, seemed pat; better simply to project — or stage — an aptly grouped period photograph of the 1874 survivors? Still, “Cold Mountain” — with Scheer’s text drawing parallels to the age of veteran burnout and Homeland Security — strikes some significant chords and makes one await Higdon’s next opera. Foglia’s accomplished production appears at Opera Philadelphia next February.

Alex Penda in Daniel Slater’s production of “Salome” at Santa Fe Opera. | KEN HOWARD/ SANTA FE OPERA

Daniel Slater’s “Salome” took chances that mostly paid off. In brilliant if too often rotating designs by Leslie Travers — costumes strictly Belle Époque Austro-Hungarian — Slater and a strong cast enacted a Freud-steeped family drama, in which Salome psychologically identified Jochanaan with her father, murdered years before by her uncle Herod, who lusts after her. Much transpired in the cistern; walled spaces opened to show the banquet, her dance and memory scenes. Salome neither stripped naked nor died; we saw zero orientalist clutter, and for the last 30 minutes only Salome, Herod, and Herodias were onstage.

David Robertson — who conducted brilliantly — cut the Jews’ cry of anguish at Herod’s blasphemous final alternate offering to Salome. Alex Penda, renamed and plunged into newly dramatic repertory, retains some of the float of her erstwhile Mozart/ Rossini Fach. Not everything was dulcet — a somewhat covered tone prevailed, and parts of the role pushed her toward semi-parlando or forcing. But she’s an arresting singing actress, phrasing thoughtfully, and a mistress of stage movement and — more vital here — its absence. Penda banished no one’s memories of Rysanek or Mattila but proved riveting on her own terms.

Clarion Robert Brubaker nearly matched her as an undilapidated Herod, for once seeming a sexual threat. Michaela Martens offered an uncommonly rich-voiced Herodias. Jochanaan — in suit and spectacles! — wrote obsessively on the desk on which he later died. Ryan McKinny — a credible object of teenaged infatuation — initially sounded grayed over, but hymned Christ’s presence in Galilee beautifully; he sounded healthiest only at full tilt, a worrisome sign. Brian Jagde’s James King-like Narraboth bespoke luxury casting. Megan Marino (Page), Tyler Putnam (Second Soldier), and Chen (First Nazarene) proved particularly sonorous.

Music director Harry Bicket led an engaged, engaging “La finta giardiniera,” making me think more highly of Mozart’s adolescent work — though it does have longeurs, so that the cuts here were welcome. Hildegard Bechtler’s set utilized the perspective of the opening-backed theater and facilitated the frequent entrances and exits that Tim Albery had the love-besotted characters do to punctuate the many da capo structures.

Altitude may have caused the otherwise very capable, stylish ensemble cast to break up long roulades. Tall, comely Joel Prieto sounded rather monochrome as Belfiore, a part aced 19 years ago at Glimmerglass by William Burden, here a clarion, amusing, and long-breathed Podestà. Susanna Phillips, caution thrown to the evening’s considerable winds, channeled Fiordiligi as his demanding niece Arminda. Lacking trills, Cecilia Hall in other respects excelled in the “pants part” Ramiro. As the titular countess-posing-as gardener, Heidi Stober gave a committed, stylish performance, fluent if not individually memorable of timbre. Joshua Hopkins’ rock-solid Nardo and Laura Tatulescu’s spirited, resinous Serpetta did the resourceful “lower orders” parts ideally.

Back at Mostly Mozart (August 11), George Benjamin’s much-discussed 2012 “Written on Skin” had an invigorating New York premiere, with Alan Gilbert leading a charged yet sensitive Mahler Chamber Orchestra. A striking score, beautifully orchestrated and set for voices, it affirmed its “instant classic” status. Martin Crimp’s brilliant libretto doesn’t wear its post-modernism lightly; the multiply-framed narrative scarcely needed Katie Mitchell’s attractive staging to be quite so distractingly tricked out with bustling, efficient young extras in black.

Though uncharacteristically threadbare in lower notes, Barbara Hannigan sang with consummate ease and musicianship and acted up a storm as Agnès. Oddly, Crimp positions her as gaining feminist consciousness, yet — as in old misogynist narratives of Eve — assigns her all the decisions that lead to ruin. As her “Protector” husband, Christopher Purves, a superb singing actor, packed meaning into every syllable of song and quasi-parlando utterance. Tim Mead, less expressive verbally than his colleagues, produced angelic tone color that suited only part of his role; the Boy’s sensuality and artistic ambition felt rather underdrawn.

David Shengold, who writes about opera for many venues, can be reached at shengold@yahoo.com.