A State Supreme Court justice has found that New York property purchased by a lesbian partner in a Vermont civil union prior to the couple’s Canadian marriage is not subject to equitable distribution in the their current divorce proceeding.

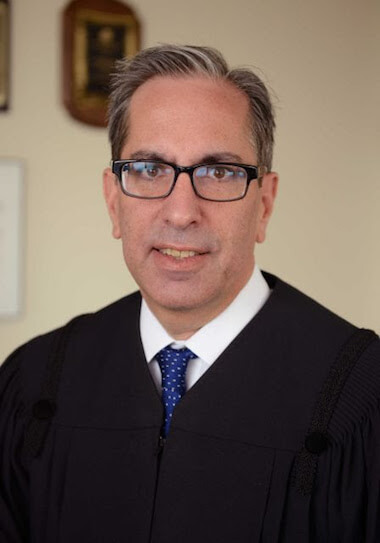

Justice Richard A. Dollinger, on October 23, found that Deborah O’Reilly-Morshead, in filing for divorce, had the right to exclude from “marital property” the house she purchased in her own name in 2004, one year after she and Christine O’Reilly-Morshead entered into a civil union but two years before they traveled to Canada to marry.

Deborah filed for divorce in Monroe County Supreme Court in Rochester in 2011, and Christine countersued, asking for dissolution of the civil union, as well, and that the house, which would be considered property of the civil union, be included as marital property in the New York divorce.

Rochester judge concludes Vermont law of no use in divorce claim for house purchased prior to Canadian marriage

Dollinger concluded that he had authority to dissolve the civil union, but that the house posed a more complicated question. Under New York’s Domestic Relations Law, “marital property” is defined as property acquired during the marriage. Dollinger concluded, “The date of marriage –– and no other date –– is the time when ‘marital property’ exists.” And, when Vermont enacted its civil union law in 2000, it expressly declared that a civil union is not a marriage.

Dollinger rejected the notion that the court treat the property the way it would be treated under Vermont law, pointing out the difficulties that would ensue in dealing with claims based on civil unions and domestic partnerships from a variety of jurisdictions over the past 15 and more years. He did note that other states, particularly in New England, had addressed this problem by including specific provisions when they enacted marriage equality laws.

“Neither the New York Legislature nor the Court of Appeals has yet moved New York’s law into the same orbit as our neighboring sister states,” Dollinger wrote. “The Legislature, in the Marriage Equality Act, simply made same-sex marriage legal in New York. It did not mandate that same-sex couples, who were united in civil unions in other states, acquired property rights through that civil union that are equal to the property rights granted to married couples.”

Dollinger considered an alternative theory of treating the Vermont civil union as equivalent to a contract under which the parties agreed that property acquired during their civil union would be deemed jointly-owned property. While acknowledging that Christine’s argument along these lines “has a power logic,” the judge concluded that it went beyond what he was authorized to do under current law.

The state’s highest bench, the Court of Appeals, he noted, had raised concerns on this score about “amorphous” agreements that would not provide the kind of “black line” test that the term “marital property” provides. Even though Vermont’s civil union law was not “amorphous,” Dollinger concluded that given his “limited authority” it was “unwise” for him to reach for a conclusion favoring Christine.

Ultimately, Dollinger found that the failure of the New York Legislature to pass any statute recognizing out-of-state civil unions for any purpose effectively tied his hands.

“In reaching this conclusion, the court is struck by the anomaly this case represents: this court is dissolving a pre-existing civil union, but only allowing equitable property distribution based on the couple’s marriage,” he wrote. “Any ‘civil union’ property –– which would be subject to distribution if this matter were venued in Vermont –– remains titled in the name of the current title holder and is not subject to distribution.”

Dollinger added, “Any further answer rests with the Legislature.”

The transitional type of problem this case presents could linger for many years, so it would be helpful for the Legislature to accept Dollinger’s implicit invitation to add a provision to the Marriage Equality Law specifying how out-of-state civil unions and domestic partnerships should be treated in the context of dissolution proceedings brought in New York.

Deborah is represented by Debra Crowder of Badain & Crowder, of Rochester, and Christine is represented by Vivian Aquilina of Legal Aid Society of Rochester.