While the NYPD certainly spent more time and effort spying on groups outside of the queer community, its surveillance of LGBTQ organizations began early and lasted for years.

“Mr. Wicker confined his talk primarily to the homosexual’s position and the many disadvantages imposed upon him by society,” Detective Raymond Clarke wrote in a report on Randy Wicker’s appearance at the WBAI Club at City College of New York in October 1963. “Mr. Wicker claimed that federal and state agencies have been conducting ‘witch-hunts’ in seeking and oustering [sic] homosexuals from their jobs.”

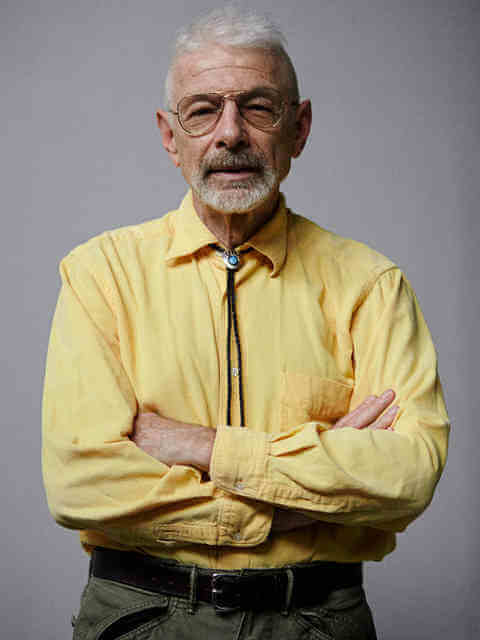

At the time, Wicker, an early LGBTQ rights activist, was the public relations director for the Homosexual League of New York. Wicker continued his engagement in community politics for decades. The campus newspaper announced Wicker’s speech, which drew 400 students, writing, “In the short space of time since he began his movement in the spring of 1962, Mr. Wicker has been called everything from ‘an earnest young crusader for the rights of homosexuals’ to an ‘arrogant card-carrying swish.’”

Clarke wrote that the PO Box for the League had been opened by Charles Hayden in May 1962 and Wicker’s name was added later. Hayden was “listed in CONFIDENTIAL undercover report 58-164,” Clarke wrote. “Postal Inspectors are conducting an investigation on this box,” he added.

But surveillance of Wicker’s group was not the earliest police investigation into organized LGBTQ political efforts. NYPD records show that detectives were attending Mattachine Society of New York meetings as early as 1959.

A hostile American society, the complete lack of legal protections, and a police force that was far more likely to arrest LGBTQ people than help them were not the sole concerns that faced the community in 1963. There were other obstacles that made using basic organizing tools difficult to impossible.

“Mr. Wicker stated that his group has been stifled by the refusal of newspaper stands and book stores to carry their writings as well as printing concerns refusing to even print their materials,” Clarke wrote.

The records of the NYPD spying on hundreds of groups are held by the city’s Department of Records and Information Services and can be reviewed at the Municipal Archives on Chambers Street in Manhattan.

The Archives have 750 cubic feet of police records that show the department’s “Italian’s squad,” which was shorthand for anarchists, spying on suspects in 1904 and then many other groups over decades. The squad became the Bureau of Special Services and Investigations and then the Special Services Division, which was the “most prolific” surveillance unit in the NYPD.

The police department’s photo unit contributed 250 cubic feet, with pictures taken from 1897 to 1975. The records on the LGBTQ groups are a small, but significant part of the collection. To date, the Archives have records through the early ‘70s.

Another detective, John Murphy, reported on an August 1966 meeting of the Mattachine Society of New York, one of several chapters in that early LGBTQ group’s history. Murphy reported that 130 people attended, including 30 women. They heard from an attorney who was representing a gay man in a deportation proceeding.

In May 1966, Detective Frank Bianco reported that two buses would be leaving for Philadelphia on July 4 from 26th Street and Broadway for the Annual Reminder Day, a protest held at Independence Hall that had gay men and lesbians dressed in business attire to show they were loyal Americans and employable. It was a reaction to the McCarthy era, which is typically represented as consisting of attacks on suspected Communists and their sympathizers, but mostly featured purges of LGBTQ people from government and private industry.

“The whole element of homosexuality in the ‘60s, it was constantly conflated with subversion, with people who were mentally unbalanced,” said Perry Brass, a member of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), an early radical group.

The NYPD shared its records with other law enforcement agencies.

“The Correspondence Unit is being requested to forward details contained in this report to the Intelligence Unit of the Philadelphia Police Department,” Bianco wrote.

For the first Annual Reminder Day in 1965, “One bus left from the New York area with thirty persons on board,” the detective wrote adding that 75 people attended that year altogether, with people coming from New York City, Washington, DC, and Philadelphia. Bianco noted that Craig Rodwell was the chair of the Annual Reminder Day Committee and Dick Leitsch was Mattachine New York’s president.

Between 1966 and 1972, the records show police spying on protests mounted by Mattachine, GLF, the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), and many other groups that joined the protests. Just six of the 19 reports were filed by patrol officers, and detectives filed the rest. Detectives often came to know participants and would speak to them on occasion.

At a February 1971 demonstration held at the city’s jail on Centre Street, Detective Francis Murphy wrote, “The following persons were observed: Mike Gimble and Frank Kameny.” Murphy took down the license plates of cars that discharged passengers who then joined the protest.

At all the protests, police diligently gathered flyers about the event or that announced future meetings of the groups involved in the actions. They also subscribed to mailings lists and gathered documents that were distributed at meetings they attended.

The NYPD ultimately collected a significant amount of material created by early LGBTQ rights groups and police shot a lot of film and took pictures of those groups.

“It does not shock me,” Brass said. “We constantly during the GLF period alluded to it, that our phones were being tapped and people were infiltrating… I think the reason the police were looking at GLF is the rhetoric was all about the radical overthrow of the government.”