Explorations of nudes and the grotesque suggest new ways of meaning

Anyone who has ever had the experience of being defined as the “other” knows firsthand the power of meanings and definitions. Polyvalence in art, as a strategy, has been one of the most powerful tools for dislodging definitions and stereotypes which can be binding, stultifying and often even violent. Artists have for centuries pushed meaning from inside itself, by exposing the arbitrary and sometime unjust nature of these definitions, thereby challenging conventional wisdom and injecting a healthy dose of new energy into the our understanding of meaning.

Art pushing meaning from inside itself is the predominate notion underlying Robert Storr’s generous exploration of the grotesque in his installment of Site Santa Fe’s current biennial exhibition. Storr, a renowned and pedigreed curator, describes the grotesque as “a full-fledged, multilayered, counter-tradition, a powerful current that continuously stirs calmer waters, sometimes redirecting their flow.”

Within the conceptual framework of the show, there are a number of compelling tributaries, which flow toward or from the work of a few particularly innovative artists.

The work brought in to relief in the most conspicuous and full-fledged manner is that of Mike Kelley—for whom Storr has great regard—and Lari Pittman. Discussing Kelley’s interest in comics, Storr argues, in a way that could describe the work of many other artists presented here as well, “It’s not a matter of debasing high art but of reminding the viewer of the actual competition it faces for their attention.”

Pittman’s recent painting, “Untitled #11,” delightfully assumes a central role in this exhibition. An exhilarating, blazing inferno of architectural, domestic, medical and tree forms is beautifully tempered and restrained by a formal style heavily inspired by the vernacular of comic books. This painting beautifully resonates with much of the other work in the exhibition. It connects to everything from the more graphic work of John Wesley, Charles Burns, Gary Panter and Raymond Pettibon (including a framed “Twilight Zone” magazine cover from 1972) to the more surreal, disturbing work of Lamar Peterson, Robert Crumb, Carroll Dunham and Hermann Nitsch. Although several of these artists have been working for longer than Pittman, it is very clear why his work, in particular, has influenced so many interesting younger artists, particularly in southern California.

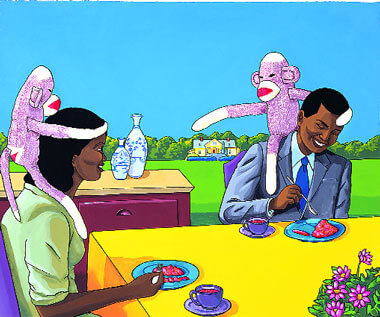

Another prominent and powerful theme that emerges during the course of Storr’s exhibition, which relates most directly to the work of Cindy Sherman and Kara Walker, is the exposure of the ugly and violent side of identity constructions. Sherman’s “Untitled (#190),” a revolting work of flesh, rotting teeth, trash, blood and viscera addresses all the things the accepted notion of feminine beauty denies, while Walker’s new video turns around the vocabulary of racist antebellum mythology and images what might happen in that ugly world if “the whites, longing for fulfillment… sold their bodies to us.” Walker’s work has always been singular and powerful, and it is nonetheless so in video. Glimpses of the artist’s body and hands orchestrating her captivating narrative illustrate indelibly the way in which we ultimately control the stories we tell.

Other “grotesque” artists working in similar veins are Lyle Ashton Harris, Sherrie Levine, Laurie Simmons, Ellen Gallagher, Jim Shaw and Lisa Yuskavage.

Several disparities animate the exhibition. The tension between the adept and nuanced painting of John Currin, Susan Rothenberg, Jenny Saville and Lari Pittman and the more unseemly subjects explored most poignantly in the work of Paul McCarthy, Kim Jones, and Tom Friedman is the most dynamic. This dynamic elegantly forces a consideration of what constitutes relevant art and, in fact, what constitutes art.

The reasons for including some of the artists only become clear by reading Storr’s catalog essay, which fleshes out his somewhat esoteric understanding of the grotesque. Semiotics is a powerful tool in both art and identity politics, but I am less convinced that it has the same force as a curatorial exercise. This show, although brilliant in parts, becomes wobbly as a whole, owing almost entirely to the curator’s semantic play on the grotesque. Its strength lies rather in its sub-currents, in its “disparities and deformations,” rather than in its headier word play.

Tattoos and demons are part of Storr’s grotesque, and they can also be found, among other things, in Athi-Mara Magadi’s solo show at Dianne Strauss’s Salon Privé. What is most memorable and moving about Magadi’s work is her sensitivity to and clear identification with her subjects, all of whom are naked and some of whom are transgendered, neither of which really matters here. Ultimately, Magadi offers a possibility over the chasm created by creating the “other.” Regardless of outward appearance, the real subject of her work is dignity and intimacy. Tattoos and demons are not at all exotic here. In their proximity, the gap closes, and the demons come home. By a very different path indeed, this exhibition arrives at a point not too far from Storr’s.