Rodney Evans imaginatively looks at the Harlem Renaissance’s gift to gay identity

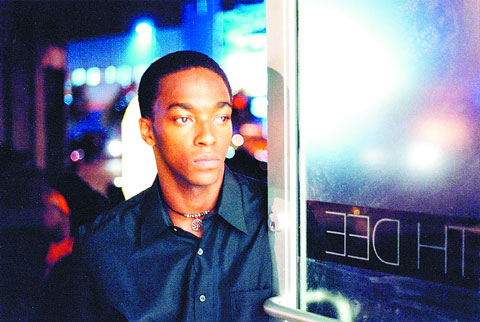

Anthony Mackie plays Perry in “Bother to Brother,” a new film that candidly examines some prominent African-American gay personalities who figured on the cultural and literary scene during the Harlem Renaissance.

A radiantly smart, deeply affecting antidote to so many cliché-ridden, black gay––hell, just plain gay––films, Rodney Evans’ “Brother to Brother” deals with the special relationship between Perry (Anthony Mackie), a college student struggling with his sexual identity and an old man (Roger Robinson) he encounters, who turns out to be Bruce Nugent, an out and proud member of the Harlem Renaissance (roughly 1920-40), who once rubbed shoulders with the likes of Langston Hughes (Daniel Sunjata) and Zora Neale Hurston (Aunjanue Ellis), who appear in the flashback portions of the film.

The film might have had a low budget––though you can hardly tell, for the elegance with which the past is recreated––but it is undeniably lavishly rich in intelligence. Evans tells the full stories of the lives of both the younger and older man with a keen sensitivity and, in the process, puts on film scenes resonantly ringing with truth, scenes, the likes of which, have never before been filmed.

Evans’ debut feature, “Brother to Brother” won the Special Jury Award at Sundance, and was shot for a mere $650,000 on the very streets of Harlem where these literary greats once walked, not far from the apartment Nugent, Hughes and Hurston shared, which they affectionately dubbed Niggerati Manor.

The genesis of Evans’ film was a 1997 video diary piece, “Close to Home,” which dealt with his coming out to his parents and the disintegration of a relationship he was in.

“It showed at Outfest in Los Angeles,” Evans said, “and someone asked me if I ever thought of writing a film based on my experience. That sparked my interest in putting my own experience into a larger narrative context. I started to think about what my life would be like in another era, which led to the Harlem Renaissance, specifically the gay underground. And you can’t venture into that territory without encountering Bruce Nugent, the first black writer to openly deal with gay themes. I went up to the Schomburg Library in Harlem, got a videotape of him and found him to be really mesmerizing.” Nugent became a sort of doppelganger for the filmmaker, as Evans realized they shared certain experiences, thought about things in a similar way, and hung out in similar places.

“I ended up developing a deep affection for him and the film is about the connection between two generations of black artists, Nugent said.

“There’s not really been a lot written about Nugent,” he continued. “‘Bruce Nugent: Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance,’ an anthology of his writing, came out in 2002. I was fortunate to find Thomas Wirth, who was good friends with him towards the end of his life and put together the anthology’s material. He’d done about 30 hours of audio interviews with Bruce towards the end of his life and was really generous in making copies of them and giving me access to unpublished writing and artwork he’d carefully preserved.”

Because Nugent dealt with gay themes when it wasn’t popular to do so, a lot of his work was swept aside and he is only now really gaining recognition and a popularity he never had in real life.

“I think he wasn’t as career-minded as Zora and Langston, not as concerned with monetary success and he had a sort of ambivalence towards making a living from his work,” Evans said. “He made work because he had to, like having to breathe. It was a necessity for him but he didn’t think of it as a commercial venture.”

As played by Robinson, Nugent is a raffish old charmer, fully aware of his ability to seduce younger men and ruefully cognizant of the price he must also often pay for this. Another actor had been cast in the role when filming began in 2001. Twenty-five percent of it had been shot when Evans ran out of money and had to postpone production for a year. His original Nugent walked, which opened the door for Robinson, “who just came in and tore it up,” according to Evans. “He was just born to play that part, with a lot of the fire that Bruce had, the energy and confrontational edge. Roger has that gritty reality in life and his performance is one of the assets of the film I’m most proud of.”

“Plus,” Evans added, ”when on film do you ever see an elderly gay man who is sexual? God forbid, they might still have desire and have that represented. With Bruce, you had to go there because that was such a hardcore aspect of his personality, being 70 and just cruising hard, and getting laid a lot. And cruising rough trade and being so charming that he could seduce these 20-year-olds because he was just such an amazing presence.”

One magical scene has Bruce repairing to his local hangout and pouring out his feelings for Perry to his bartender, who has a true commiseration that can only be described as both brotherly and sisterly.

“There’s a kind of self-recognition there,” Evans said. “A lot of people have asked me how I can be so young and understand that idea so well. I think that just comes from looking at Bruce’s experiences in his older years. It’s interesting because a lot of older people come up to me and say, ‘That’s exactly how it feels,’ and it’s cool to be able to do that.”

Evans had praise, as well, for Mackie, as Perry: “He had basically just graduated from Juilliard and had gotten a lot of buzz in a play, ‘Up Against the Wind,’ in which he played Tupac Shakur. I had originally thought of him for the part of Perry’s best friend, a poet, but he called me back and said, ‘I loved your script, but I only want to read for Perry.’ It was so refreshing for him to react that way because nine out of ten straight black actors wouldn’t read for Perry because they were petrified to play a gay part. So for him to say, ‘I’m not interested in the secondary role, but in understanding the main character,’ and be willing to put himself in risky places that were uncomfortable gave me a lot of inspiration. I got an energy boost from his bravery and it made me stronger and braver, willing to take chances.”

The fear of playing gay among black actors, Evans said, has its roots in hip-hop: “That machismo element, the reassertion what it is to be a man and the homophobia that gets espoused over and over again has a direct influence on the culture black people are involved in. Plus, there’s such a dearth of parts for black actors that they’re wary of doing anything that might stereotype them. So, unfortunately, that stigma is stronger for black actors.”

One black actor who joyfully has no problem with it, besides being perhaps the most beautiful man on the planet, Daniel Sunjata, plays Langston Hughes.

“You know, this was before ‘Take Me Out,’” Evans explained. “He hadn’t done anything before this, and was fresh out of school. He came in and read and was clearly the best actor for it. And if you look at pictures of Langston, he was stunningly beautiful as a young man. Daniel has that star presence, and a grace and dignity and an ease that is very natural.”

The always dicey subject of Hughes’ rumored homosexuality is not heavily explored here and, when asked about it, Evans chuckled.

“It’s been so speculated about and so kind of unable to be determined,” he said. “You hear so many different things. But I really wanted it to be centrally focused on Bruce, who was gay, and in your face when it wasn’t really safe to be that. I found that really encouraging and inspiring and thought the breadth of life he was able to see from this unique perspective was really interesting.”

One of the more controversial moments in the film is when Perry suddenly takes umbrage at a racially stereotyopical sexual remark his white boyfriend (Alex Burns) makes about him.

“That was really interesting because audiences at screenings read that scene differently depending on where they’re coming from,” Evans said. “Some people didn’t understand why Perry was so offended and others completely understood, saying, ‘I was right out of that room with him, immediately!’ We made choices in the editing room. We could have had him say something much more offensive and made it more clear that he was in the wrong but I wasn’t interested in demonizing all the white characters.

“I was interested in that kind of complexity. It’s one of the themes that stays with people, grappling with it, and I’ve had people e-mail me about it weeks later. I was really interested in these people from completely disparate worlds trying to open up to each other and connect, that thirst for common ground and trust.”

Originally from Queens, Evans attended film school on the West Coast at Cal Arts and began doing documentaries. “Unveiling,” his thesis film, dealt with gay and lesbian strippers in the black and Latino community, “focusing on three characters, one of whom, a black woman, performs for predominantly female audiences and is a single mother and Jody Whatley’s sister, filled with all sorts of drama. His 1999 “Two Encounters” examined race in the gay community.

“I had a gay white and a gay black man wired with hidden cameras, going to predominantly white and black bars, and tried to capture what it’s like to be ‘the other’ in those kinds of environments,” he said. “A lot of stuff came through just through gestures and glances. In the black bar, a white guy came up and said, ‘So, you like chocolate?’ which leads to this whole argument about fetishization. Then my friend, Steven was the one black person in G Bar, and has someone coming up and asking if he’s black and then talking to him about his experiences with black men and finding out that they’re usually either hyper-effeminate or think they’re God’s gift to the world.”

Evans is currently unattached and laughingly said, “I’m available. Tell your readers. Actually, this film has been so all-encompassing I haven’t had time for a relationship and don’t know where that would fit in. But I’m open and looking!” Making “Brother to Brother” took six years and was a hard sell for its very uniqueness. Two recent black efforts, “Ski Trip” and “Noah’s Arc,” represent the direct opposite side of the cinematic scale, with their plethora of sometimes amusing but decidedly stereotypical bitchy queens, macho trade and––in both cases––central protagonists who are questioning their identities in an indeterminate and ultimately bland manner.

“I think that’s a very specific and different agenda,” Evans said. “A lot of filmmakers see these white gay fluffy romantic comedies and really want to make films like them, but they just want to have black people in them. That’s a very specific interest that is not mine, but I think there’s room and applaud them for that.”

Evans offered an overview of the vision he would like to achieve.

“I definitely want to do something totally different, dramatic and grappling with history,” he explained. “I really had to fight because a lot of people have very myopic ideas of what film can be. So if you have a parallel structure that is moving back and forth between past and present, that’s constantly questioned. Or a fictionalized encounter between James Baldwin and Eldridge Cleaver has people concerned that the audience is going to be confused. My whole thing is, let people think for a second, don’t spoon-feed them. I think that kind of thought pattern is why films are so predictable; you know in the first five minutes exactly where they’re going.”

Evans hopes to do something different: “I think most filmmakers make the kind of film they hunger to see: a black gay character that’s not a drag queen-comic relief-high snap diva but actually is complex and layered.”