Pondering freedoms as applied to Lenny Bruce during the war on terror

“Jesus Christ, the Pope has forgiven the Jews.” That jolting, cynical line—it’s by Robert Shaw (yes, the actor), and it opens Shaw’s 1967 novel from which came the play and movie “The Man in the Glass Booth”—is what shot into my head the day before Christmas when I heard that Gov. George E. Pataki had pardoned Lenny Bruce 37 years after his death and 39 years after Bruce’s conviction for “obscenity” during a performance at Bleecker Street’s Cafe Au GoGo in the summer of 1964.

The irony of it. Oh God, the irony of it. Multiplied by the fact that the pardon had come wrapped in sententious words about free speech as one of “the precious freedoms we are fighting to preserve as we continue to wage the war on terror.”

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s Lenny Bruce, Superdude, versus Osama bin Laden, oy vey. But let us not be ungrateful for mixed favors. A pardon is a pardon and a politician is a politician.

The thing is, Mr. Pataki, your horizon was a bit limited. Freedom of speech, yes, and then some.

“His gospel [I once wrote of Lenny] was freedom: sexual freedom, racial freedom, religious freedom, cliché freedom, hate freedom—in short, happiness through truth. Bruce [‘sick comic’ to a predominantly wolf-pack press] enraged many people, including some arresting officers and psychiatrists and judges and prosecutors and critics who by the record of their lives and deeds were at least as sick as he was. But wasn’t that what his whole schtick was about?”

It was Lenny Bruce who crashed through barriers, spearheading the way, just as Jackie Robinson did, just as Lorraine Hansberry did. In Lenny’s case, he opened the gates for an army of wits, half-wits, and no-wits who have since deflowered and devalued their, and our mother tongue, to an extent that would have turned Lenny vehemently off.

“When I’m interested in a truth,” he had said to this reporter one hot day in that summer of 1964—we were in his cruddy, jail-sized hotel room in the Marlton on Eighth Street, with legal papers and transcripts and ampules of what he said were amphetamines scattered all around – “it’s really a truth-truth, 100 percent—and that’s a terrible kind of a truth to be interested in.”

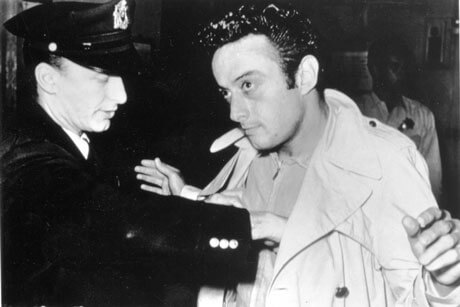

As it happens, I had seen his act at the Au GoGo, had covered it, reviewed it, and during it had watched him banter with the undercover cop or cops he was sure were taking notes.

The weird thing is, Lenny’s heart went out to cops. “I have a lot of sympathies for the peace officers,” he’d told me. “Actually, the policeman is the postman. He’s just the guy who delivers the mail . . . They’re very civil; it makes you cry . . . They die for $400 a month, and people like The Liberal, they force the policeman into that other image.”

As it further happens, this journalist subsequently had the opportunity to read the prosecution’s transcripts of what some peace officer or officers (or license inspector) had said Lenny Bruce had said and done in that Au GoGo performance.

“What with misquotes, misunderstandings, gaps, transpositions, words badly heard, words unheard, errata, typos, garbles, and sheer human ignorance,” I would report, “they bore as much relation to what Bruce had actually done and said that night as a gorilla does to a Pekinese.”

And that gobbledygook is what got Lenny Bruce convicted of obscenity, in the great state of New York, in 1964, thanks to an ambitious jackal of a then assistant district attorney named Richard Kuh, and Kuh’s boss, District Attorney Frank Hogan, a stiff-necked old warrior for whom Lenny’s freedom of speech touching on the papacy and related matters had been a lot too free.

The chief judge on the panel hearing the case was another ironpants, named John M. Murtagh. Lenny begged to be allowed to do his act before the court, but Murtagh turned him down. Instead, the license inspector, Herbert G. Ruhe, ploughed his way through those transcripts in a monotone. Said Lenny, as The New York Times reminded us last week: “This guy’s bombing and I’m going to jail for it.”

It was true, except that he didn’t go to jail. He went off to California, and two years later he was dead on his bathroom toilet, and the police made sure the press came in to see. In fact, for all his admiration of the police, Lenny Bruce did not die of drugs per se. Like Billie Holiday before him, he died of cops.

Ever and again, when I think of Lenny, I think also of a tall, slim, beautiful girl whose name I do not know and whom I saw only for a couple of minutes one cold winter night in the early 1960s on the sidewalk of 43rd Street outside Town Hall. Lenny was to give a late-night performance in that sanctified venue, and there were several dozen of us, standing, stamping, waiting, for the chamber music concert that was in progress to end and be let out, so we could go in. Then at last the chamber concert did end and the concertgoers streamed out, among them one well-dressed middle-aged gentleman who looked around, puzzled, at our gang. “What are all you people waiting for?” he asked, only to receive—from that tall, slim, beautiful girl—the split-second reply: “Meeting of the B’nai B’rith.”

Lenny would have eaten her up.

From the review of the Au GoGo performance that got Lenny busted:

“No doubt it is a rare, sick need, this hunger for a shred of sanity in a universe where sanity is out of fashion. Yet how restorative to have just one nose-thumbing soothsayer arise to say, to the whole show, that the emperor not only has no clothes on but he faces the faucets [i.e., in a Lenny confessional, sometimes pees in the sink] just like you and me.

“It is indeed a need. On the way to the concentration camp one could have died a little better with a Bruce in the same cattle car.

“ ‘Whaddya expect, man?’ he would have said. ‘Ya gotta pay those dues.’ Then he would have added a couple of words—Yiddish, censorable, precise, and soul saving—about the curious habits of the S.S. police dogs.

“The world is never short of concentration camps. Bruce stands up against all limitations on the flesh and spirit, and someday they are going to smash him for it.”

Which they did. It has taken 39 years, but guess what, Lenny. You have been forgiven. Pardoned. Miracles never cease.