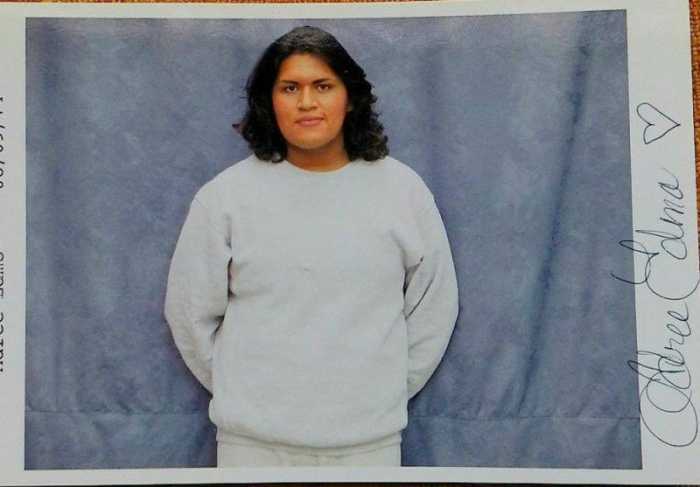

BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD | A federal appeals court has found that conditions for transgender women are so dire in Mexico that they may qualify for protection in the US under the international Convention Against Torture (CAT) based on the likelihood they would face torture if deported. On September 3, a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco ruled on cases involving Edin Carey Avendano-Hernandez, Fidel Mondragon-Alday, and Daniel Godoy-Ramirez, each identified as an immigrant transgender woman.

In opinions written by Judge Jacqueline H. Nguyen and joined by Judge Harry Pregerson and Judge Barrington D. Parker, Jr., the Avendano-Hernandez case presented the most complicated factual issues and was the one where the panel spelled out its analysis in greatest detail.

Avendano-Hernandez grew up in Oaxaca, Mexico, and though identified male at birth, “she knew from an early age that she was different,” Nguyen wrote. “Her appearance and behavior were very feminine, and she liked to wear makeup, dress in her sister’s clothes, and play with her sister and female cousins rather than boys her age. Because of her gender identity and perceived sexual orientation, as a child she suffered years of relentless abuse that included beatings, sexual assaults, and rape. The harassment and abuse continued into adulthood, and eventually, she was raped and sexually assaulted by members of the Mexican police and military.”

Ninth Circuit concludes abuse amounting to torture likely if three immigrants sent back home

Even though the Immigration Judge (IJ) who first heard the Avendano-Hernandez case accepted her testimony about what she had suffered in Mexico as credible, both that court and the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) ruled against her claims.

Avendano-Hernandez’s case was hurt by a number of factors: her failure to seek amnesty immediately after arriving in the US, alcohol abuse that led to a felony drunk driving conviction, and her failure to abide by the resulting parole conditions. Among a variety of potential avenues for her to try to stay in the US, the IJ found the only one that remained open to her was protection under the CAT.

In evaluating whether she faced the likelihood of torture if returned to Mexico, both the IJ and the BIA conflated sexual orientation and gender identity and concluded that life for gay people in Mexico had improved enough –– given progress on nondiscrimination protections, adoption, and marriage equality –– to preclude Hernandez’s CAT claim. The available evidence, however, suggests there has been far less progress on matters of gender identity, but neither the IJ nor the BIA credited Avendano-Hernandez’ testimony about the likelihood she would suffer torture in the future.

“The IJ and the BIA do not appear to question that the assaults and rape of Avendano-Hernandez rise to the level of torture,” Nguyen wrote, pointing out that she was singled out for this treatment due to her “transgender identity and her perceived sexual orientation,” as evidenced by the language used by police officers and soldiers when attacking her.

“Rape and sexual abuse due to a person’s gender identity or sexual orientation, whether perceived or actual, certainly rises to the level of torture for CAT purposes,” she continued. “The agency, however, wrongly concluded that no evidence showed ‘that any Mexican public official has consented to or acquiesced in prior acts of torture committed against homosexuals or members of the transgender community.’ In fact, Avendano-Hernandez was tortured ‘by public officials’ –– an alternative way of showing government involvement in a CAT applicant’s torture.”

Nguyen specifically challenged the notion that Avendano-Hernandez’s abuse was unlikely to be repeated.

“We reject the government’s attempts to characterize these police and military officers as merely rogue or corrupt officials,” she wrote. “The record makes clear that both groups of officers encountered, and then assaulted, Avendano-Hernandez while on the job and in uniform.”

The appeals panel insisted that the applicant for CAT protection need not show that high government officials are involved in her torture.

“It is enough for her to show that she was subject to torture at the hands of local officials,” Nguyen wrote.

The BIA had discounted the potential for Avendano-Hernandez suffering future abuse, pointing to the passage of laws in Mexico “purporting to protect the gay and lesbian community,” an analysis the appeals panel concluded was “fundamentally flawed” because it assumed, without any evidence, that such laws would also benefit Avendano-Hernandez, “who faces unique challenges as a transgender woman… [R]ecognizing same-sex marriage may do little to protect a transgender women like Avendano-Hernandez from discrimination, police harassment, and violent attacks in daily life.”

The dangers facing transgender Mexicans is amply documented, the panel found.

“Country conditions evidence shows that police specifically target the transgender community for extortion and sexual favors, and that Mexico suffers from an epidemic of unsolved violent crimes against transgender persons,” Nguyen wrote, pointing out that Mexico “has one of the highest documented number of transgender murders in the world.”

And, the appeals panel pointed out, the highest level of hate crimes occur in Mexico City, the jurisdiction with the most protective legislation regarding the gay and lesbian community.

Instead of returning the case to the BIA for further proceedings, the appeals panel took the very unusual step of ordering immigration officials to grant Avendano-Hernandez CAT deferral relief “because the record compels the conclusion that she will likely face torture if removed to Mexico.”

The Ninth Circuit’s conclusions in the other two cases followed from its analysis regarding Avendano-Hernandez. Despite affirming an Immigration Judge’s conclusion that Fidel Mondragon-Alday’s credibility suffered due to inconsistencies between her written and oral testimony, it found that because there was no dispute she is a transgender woman, even in the absence of credible evidence of past torture, “a ‘likelihood of future persecution may still be sufficient to merit withholding of removal.’” Because the BIA had erroneously relied on protections for gay and lesbian people to discount the possibility of future persecution of Mondragon-Alday, the case was sent back for reconsideration, with a specific directive to “consider the particularized dangers faced by transgender women” in Mexico.

In the third case, the appeals panel found that the Immigration Judge violated Daniel Godoy-Ramirez’s due process rights by failing to explain the avenues available to her for redress, in particular an extension of the one-year filing deadline for asylum protection. Godoy-Ramirez’s “record,” the Ninth Circuit found, “contains significant facts that suggest her possible eligibility” to have her case heard, “including being thrown out of her home for being transgender, the time she spent living on the streets, and her young age at the time of removal proceedings.” The case was sent back for reconsideration, with Godoy-Ramirez given the right to argue she is eligible for the asylum filing deadline exception.

Beyond the IJ and BIA’s failure to accord her appropriate due process, the panel concluded they also erred in finding she had not suffered past persecution in Mexico, despite “direct evidence that Godoy-Ramirez was raped on account of her transgender identity and presumed homosexuality… The BIA failed to acknowledge that Godoy-Ramirez’s rapist repeatedly used homophobic, derogatory language while raping her.”

As a result, the BIA was directed to reconsider Godoy-Ramirez’s claim of CAT relief as well an alternative avenue of withholding of removal. It seems likely that Godoy-Ramirez will qualify for some form of relief and will not face deportation.

These three opinions make a strong case for assuming that virtually any Mexican transgender woman whose gender expression and appearance were likely to make her a target of the police and military should be entitled to find refuge in the US. Time will tell if the BIA takes the court’s conclusions to heart as it hears future cases.