UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN PRESS

Andrew Evans is an author, travel writer, and TV host, working in a variety of media. One of his nicknames is the Digital Nomad, especially for his work for National Geographic, reporting live from all seven continents and more than 100 countries. He has broadcast from kayak, camelback, and helicopter, from atop arctic glaciers, from the jungle, from the middle of the ocean, and from inside King Tut’s tomb. He was the first person ever to live-tweet his ascent of Mt. Kilimanjaro and gained a worldwide following when he made his overland journey from National Geographic headquarters all the way to Antarctica, using public transportation.

Evans holds degrees in Geography and Russian Foreign Policy from Oxford University, and when he is not traveling, he lives in Washington, DC. His website is AndrewEvans.org.

From a shy Mormon upbringing to a life well lived around the globe

Evans has written for National Geographic, National Geographic Traveler, Afar, BBC Travel, Outside, Smithsonian, Readers Digest, the Chicago Tribune, the Guardian, and the Times of London. He is also the author of five books, including two bestselling guidebooks, and the travel memoir “The Black Penguin,” recently published by the University of Wisconsin Press. The book details his early life growing up Mormon, coming to terms with being gay in a conservative environment, and his ultimate exploration of much of the world. Gay City News recently chatted with Evans about his book and his adventurous life.

MICHAEL LUONGO: What is the meaning of “The Black Penguin?” Is it another way of saying the black sheep, or about something elusive and rare, like a black swan?

ANDREW EVANS: I don’t ascribe any particular meaning to the black penguin. It’s an apt description for the extremely rare bird that I spotted in Antarctica right at the end of my journey. It became the title of my book for several reasons — symbolically, yes, perhaps, but also the kind of rare prize that I discovered at the end of the road.

ML: What was it like for you growing up gay and Mormon in Ohio?

AE: Difficult and painful, because despite having a very loving and close-knit family, I was well aware that our religion was in direct conflict with who I was as a person. It meant that for years, I lived in secret, knowing that at some point I would reach a monumental impasse. Honestly though, the homophobia and bullying I experienced at my school in small town Ohio was so much worse. I like to think that things have improved for kids in schools today, but based on what I read in the news, bullying and homophobia are still a huge problem.

ML: When did you first realize as a child that there was a whole world out there?

AE: I always knew it. When I was 15, I convinced my parents to go somewhere foreign, meaning to Montreal. I had never smelled a fresh-baked croissant until that moment, in Canada, when I realized that the whole world was full of exciting, exotic things I knew nothing about. That’s when I knew National Geographic was not a lie.

Travel writer and digital nomad Andrew Evans. | UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN PRESS

ML: How did you wind up becoming the National Geographic Digital Nomad?

AE: I was the first writer at National Geographic ever to be assigned a live, interactive social media-based feature. At the time, the entire Internet fit under the category of Special Projects and so nobody paid much attention to what we were doing. My trip to Antarctica garnered a mass following, though, and after that, my editor Keith Bellows called me Digital Nomad. That became my official title and my full-time job for about four years. Sadly, after a while, the position became a euphemism for sponsored content, so I moved on. Now I’m just a writer, or contributor, and am very grateful and honored to work for National Geographic all around the world.

ML: What was Brigham Young like as a gay student — was there a sense of gay life among friends?

AE: Terrifying, because we had to remain closeted and we were always so scared of being discovered, outed, or turned into the administration. Based on my own experience, I would say that BYU offers the least healthy environment for LGBT college students in America today. The only gay life we did have was kept secret and underground, and I witnessed several friends be expelled after they were outed. I was forced to undergo so-called “reparative therapy” in order to stay at the university and was spied on by the administration for the duration of my education.

ML: What is the relationship between travel and exploring one’s sexuality, or growing comfortable with it?

AE: I think they are parallel paths that play off one another. So many of the gay men I know only truly came out of the closet when they had traveled and lived far away from home, to a place so foreign they could be anonymous. This is the whole plot of Christopher Isherwood’s “Berlin Stories” as well as so much gay literature — we can’t really be ourselves at home so we leave home and let loose with all of our personality and sexuality.

Home represents the confines of society and life expectations, meaning one’s sexuality can be very defined before it’s ever been experienced. Travel drops us into settings where nobody has any expectation from us, and where the definitions of home don’t always apply.

ML: Why Antarctica by bus? Sounds crazy!

AE: Perhaps I am crazy but, honestly, I was so desperate to get to Antarctica, I was ready to try anything. I had failed at getting jobs there, joining trips and expeditions. I got so depressed about it, I kept studying the map. That’s when I realized that I was focused too much on the destination, rather than the journey. And on the map, I saw road systems that stretched all the way from my house all the way to the bottom of South America, which was most of the way. That’s how I got the idea to take public transportation and live-tweet my journey from beginning to end.

ML: Travel and travel journalism sounds glamorous, but what would be surprising to many people about it?

AE: Travel is exhausting, and it can also be very depressing, lonely, difficult, stressful, and downright deadly. I think travel journalism depicts the world at the highest moment — by the pool with a cocktail or smiling joyfully next to some World Heritage Site.

What they don’t show is getting stuck at Newark Liberty for 17 hours, or the projectile vomiting that follows parasitic infection. I think everybody dreams of being a travel journalist, but those of us who actually do it spend a lot of time complaining about how nobody knows how difficult and thankless it can be.

ML: What is your favorite part of the book “The Black Penguin?”

AE: That’s tough. Some of my favorite parts got cut in the final edit. I think I always love re-reading the scenes from my childhood because writing this book really helped me understand myself better. I also love remembering how crazy my trip got in Bolivia, so the Bolivia chapters for sure.

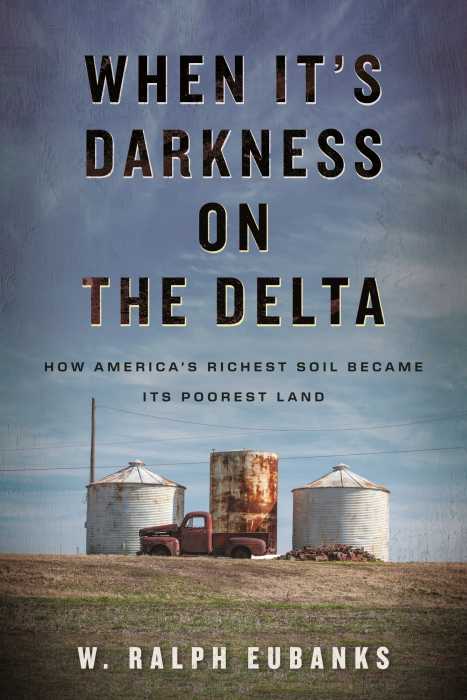

THE BLACK PENGUIN | By Andrew Evans | University of Wisconsin Press | $24.95 | 304 pages