South African performer hands a shovel to the head-buried president

Evita Bezuidenhaut has big hair, dangling earrings, an armful of little black dolls—she was once Ambassador to the black homelands—and a smirk that would send you scooting from Capetown to Pretoria. She currently gets through life on fears and denials.

Her sister Bambi Kellerman has somewhat fatigued golden hair, pearls at her neck, a mink stole around her shoulders, and a rubber penis close at hand. Following the death of her husband, Paraguay’s Nazi minister of war, she is now back running a string of brothels in South Africa. And oh yes, she has AIDS.

Pieter-Dirk Uys does not, outside of the theater, look like either of these ladies. A large, husky type in a longshoreman’s navy-blue knit cap, he looks like one of the roust-abouts scrambling for work in “On the Waterfront.” Put him on stage, replace the knit cap, and he becomes Evita Bezuid-enhaut and Bambi Kellerman in the flesh.

Simultaneously?

“Well, I try,” Uys said with a smile. “It’s very difficult.”

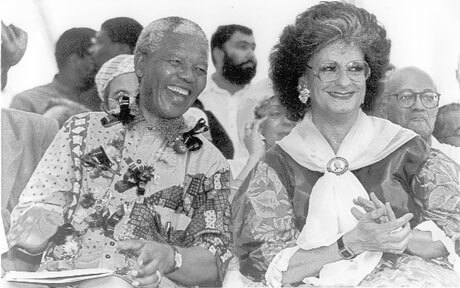

In “Foreign Aids,” the one-man show Uys (pronounced “Ace”) has brought to La Mama E.T.C. on East 4th Street, he also variously becomes Nelson Mandela, Bishop Desmond Tutu, and South Africa’s incumbent President Thabo Mbeki—who, to Uys’ despair, outrage, and scorn, recently went on record to announce: “I don’t know anyone with HIV… Personally, I don’t know anyone who has died of AIDS.”

Mbeki stonily and insanely refuses to recognize that there is a direct connection between HIV, the virus itself, and the onset of AIDS-related symptoms. It is appalling that the president of a nation where five million out of 40 million citizens are now HIV-positive and more than 600 people a day die of AIDS-related diseases remains so oblivious. Of the Thabo Mbeki he once admired as Mandela’s partner in the fight against apartheid, stark-serious comedian Uys now says: “He lies, and he condemns his nation to death.”

Not just death, but genocide.

“The word is mainly associated with the Nazi extermination of millions of Jews, gays, gypsies, and others during World War II,” said Uys, gay and the son of a Berlin-born Jewish mother. “But does genocide always have to be at the end of a machine gun? Do we have to kill six million and one people to be worse than the Nazis? [Mbeki’s] strategy is starting to look like a systematic planned extermination of those who are poor, unemployed, in prison, on the streets, and hopeless. The new apartheid has already established itself. Black and white South Africans will live. Those without money will have no access to medication and drugs. They will die.”

Beyond the daily 600 each day in South Africa, the total for all of southern Africa—Botswana, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, South Africa—is, said Uys, 3,000 deaths a day.

“Pretty clear to a New York audience what that is,” meaning, a September 11 disaster every 24 hours.

“What’s ironic is that after winning the battle against apartheid, the battle against AIDS is more terrifying and more devastating.”

Intense as Uys’ straightforward letters-to-the-editor anger can be, his main performance weapon is, naturally, satire, honed in his own Capetown cabaret—ergo the Madames Evita and Bambi. And nothing so provokes authority—all authorities, everywhere, any time—as satire.

“I used to say that governments swipe my material. They still do,” said the man in the longshoreman’s knit cap, a few days before his October 23 opening at Ellen Stewart’s La MaMa, regarding a recent stilted attack on Uys as a “house clown [with a] self-serving and… malicious agenda” from the desktop of a Mbeki minion named Essop Pahad.

“An extraordinary statement,” said Uys, “rather like a Stalinist thesaurus translated into 1950s English.”

Reverence is not part of Uys’ act, nor of what he said and did in his visits these past four years to some 400 schools throughout South Africa—“one million kids so far”—plus reformatories and prisons.

“Here I am, standing in a school hallway, talking about the birds and the bees. ‘How does a bird fuck a bee?’ I ask. That works. It causes a commotion. But it’s language the kids understand.”

Of all the millions now being stricken with AIDS every day in South Africa, how many are black, how many white?

“More black than white, but nobody sits out the dance. Most whites have facilities to fight AIDS, and also the knowledge.”

How about yourself?

“I’m scared. I’m vulnerable.” He looks for wood to knock on, but the coffee table is made of metal.

No, Pieter-Dirk has no partner at the moment, “but I’ve had many, and I’ve buried many friends. When I go to the HIV test, I’m nervous. I suppose one day I’ll have to live with it like everybody else.” A fleeting smile. “These days it’s cats and dogs. Unrequited love. There’s a saying that dogs have owners, cats have staff. That’s very much the case with me.”

Pieter-Dirk Uys, who lives in the little village of Darling, outside Capetown, was born in Capetown on September 28, 1945. His mother, Helga Bassel, was a concert pianist who got out of Germany in 1938, when she was in her early 30s.

“It was only after she was dead that I found out she was Jewish,” he said. “I’m now trying to catch up.”

His father, Hannes Uys, also a concert pianist, was of fourth-generation Dutch-Belgian Huguenot stock—persecuted 17th-century Calvinist Protestants—“and my sister Tessa, who lives in London, is also a pianist, so when I was little, Mozart was my pal.”

A cousin is Jamie Uys, director of the low-cost worldwide 1980 hit film “The Gods Must Be Crazy,” about a Kalahari bushman who encounters the 20th century by way of an abandoned Coke bottle.

How had Hannes Uys stood on apartheid?

Silence and long thought from his son. At length, word by word: “He was a decent man, and not somebody who allowed the laws to give him freedom of racism. We lived in a white area. I went to white schools. Of course when I was fighting apartheid I had to fight my father too. But gradually he came onto my side—which was good.”

During his battles against apartheid, Pieter-Dirk Uys had to keep his homosexuality secret “so as not to enable the [P.W. Botha] government to paint me into a corner.” That’s over with, at least.

Botha, the ironclad bigot, was easy to understand. How does one explain the wacko refusal of Thabo Mbeki to face up to the realities of HIV and AIDS?

“I don’t know… It’s beyond logic… I don’t know… I used to like him enormously, back when Mandela was president. Mbeki is a very intelligent man. He had a great sense of humor. He was educated in the U.K., which meant he grew up with Monty Python and all that. He also went to Moscow University, and he actually is a Stalinist.

“But it’s just baffling. Is he trying to save money, allowing the poor to die, which is indeed genocide? Has he got AIDS and is in self-denial? I don’t know.”

For all the verbal attacks on him by Mbeki’s flunkies, Uys does not bear the burden of feeling threatened.

“When I’m threatened, it becomes inspiration. I put it in my material the next night.”

Evita Bezuidenhaut and Bambi Kellerman are at La MaMa through November 9 to tell you all about it.