Photographs spanning nation’s history examine most vexing nuances of divisions

Any project that aims to investigate something as vast and layered as American racial identity, or lack thereof, has at least 300 million factors to consider: 300 million subjects created from an amalgam of experiences. It is an undertaking, by definition, riddled with concerns of politics, representation, organization, perspective, and, of course, the big kahuna underlying all of these, power.

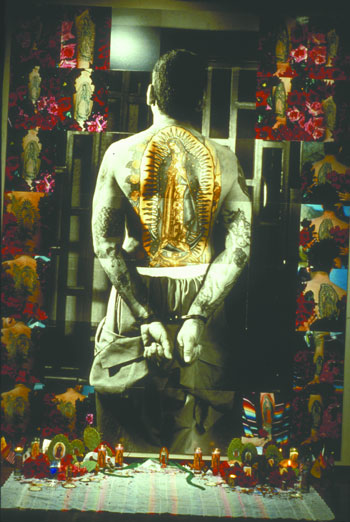

“Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self,” an exhibition at the International Center of Photography, throws itself into that fray and still manages to get at its topic, albeit obliquely.

Although the curators, Coco Fusco and Brian Wallis, claim that this is the first comprehensive look at these issues through photography, many of the themes and artists they highlight are familiar to followers of contemporary art, who may recall the controversial 1993 Whitney Biennial. More than a decade later, it is useful to reflect on what has happened since then and, as well, to see these issues in a larger context. Included in the show are a number of historical, journalistic, and anthropological photographs, which function as a foil and frame to works by leading contemporary artists. Among these images are anthropological images of slaves and Native Americans from the 1800s, covers of Time magazine––O.J. Simpson and “The New Face of America,” a digitally altered image of a woman’s face assembled from a composite of racial features––and photojournalistic images from the civil rights era, the Mexican migrant worker struggles, and the recent political protests in Vieques.

Any exhibition that begins with Vanessa Beecroft’s “VB 39, U.S. Navy Seals, Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego” gets my attention. It is a large photograph of a performance/installation where the artist brought together a group of Navy Seals to stand firmly at ease and stare straight ahead for hours while museumgoers meandered around looking at them. It puts masculinity on display in a very exciting and provocative manner. Also visible from the entrance in the background to the right is a large scale work by Barbara Kruger, which features an apparently crumbling and decaying photograph of the female head of a classical Western sculpture inscribed boldly with the words “Your fictions become history.” These pieces, which set the tone of the show, have as much to do with gender constructions as with race, but nonetheless, here they are introducing this show.

The complications and difficulties of putting on this kind of show are endless. Organized along the themes of five scantily sketched themes, the show succeeds in spite of its unwieldy scope. I suggest approaching it in a very personal manner, choosing private inroads into these pieces, rather than thematic or intellectual ones. Find yourself in the exhibition first and see where that takes you.

The experience is like that of an archaeological dig. It exposes ruins and structures hitherto unknown, unexplored, or unconsidered, and by bringing them into view, sheds new light on current mythologies. I identified with a number of images, causing me to pull out images and memories from my own life––growing up in rural New Mexico in the 1970s to coming out in New York in the identity politics-laden world of academia in the 1990s. In a strange way, it was like perusing a personal photo album embedded within a collective image bank.

This exhibition reveals how our private mental images create a sense of who we are––or think we are––and moreover, how we think of others. It is a lot to get out of a photography exhibition, and I’m not sure whether it speaks to the power of these images or to the canniness of their curators. Regardless, it is enlighteningly familiar.