The work of Patricia Highsmith, largely ignored, discussed at Housing Works Used Book Café

Patricia Highsmith’s life has remained as shrouded in darkness as the best of her legendary crime novels. Largely unheralded in this country during her lifetime, and cursorily labeled “the mystery girl” by critics, Highsmith was best known for her character Tom Ripley, who was the subject of five of her books and several film adaptations.

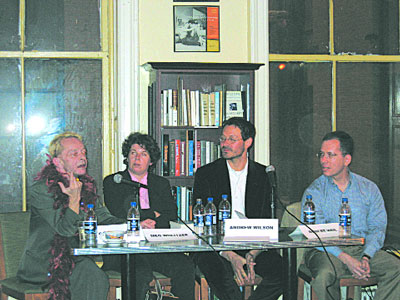

To honor Highsmith and to celebrate the release of her first biography, Housing Works Used Books Café—a rare and used bookstore affiliated with the AIDS advocacy organization Housing Works—hosted a panel discussion on Saturday, May 8 featuring the authors Wilson, Meg Wolitzer, and Gary Indiana and Robert Weil, the senior editor at W.W. Norton. Weil is largely responsible for getting 18 of Highsmith’s novels published since her death in 1995, at which time only four of her 22 books were in print in the United States.

Born in Fort Worth, Texas, Highsmith graduated from Columbia University in 1942 and then lived much of her life in England and France, before her death in Switzerland in 1995. Highsmith’s 1952 novel, “The Price of Salt,” was one of the first books to focus openly on a lesbian relationship, and, like other lesbian novels of the period, was relegated to the sordid realm of “pulp” fiction. The book was sold for 25 cents at neighborhood drugstores, but it spoke to thousands of gay Americans at a time when the lack of a cohesive gay community resulted in an overwhelming sense of isolation for most gay men and lesbians.

Despite her role as a pioneer, however, Highsmith did not speak openly about her sexuality—or indeed her work—while she was alive.

“Publicly, she was reluctant to talk about her writing because she knew [her subjects] were so close to home,” commented Wilson during Saturday night’s event.

Each of the panelists read several passages from their favorite Highsmith writings and subsequently commented on their choices. Gay author Indiana had to stop just short of the end of his Highsmith selection, the short story “Born Failure,” when he became overwhelmed with emotion.

“I think I forgot how deeply it affected me,” he said. “[But] I wanted to read it because even though it’s extremely sad, it’s in a strange way exalting.”

Indiana cited Highsmith as “probably the most important writer in my life, and arguably one of the best writers of the last 50 years.”

Wilson, who is a British journalist and first-time biographer, read excerpts from his 2003 life of Highsmith, which he began working on since 1995. Wilson had access to all of Highsmith’s personal papers and diaries, as well as the benefit of interviews with some of her closest friends.

Although in life she likened the notion of having her biography written to “vultures swarming around her,” Highsmith, Wilson noted, left all of her papers in perfect order “as if she was just waiting” for someone to pour through them and tell her story. The papers allowed Wilson to provide a deeper insight into a complex woman whose life was full of pain and contradiction from the start, and whose vision was never fully embraced in her native country. Indiana noted that “in Europe, her books are considered literature. They are in the literature section at bookstores. Here they are considered mysteries.”

In the question-and-answer period following the panel discussion, one audience member suggested that Highsmith’s reception in America might have to do with the fact that her subject matter is overwhelmingly dark: “American readers think they’re innocent; therefore, her ideas did not sit well… Americans need to accept the darkness in their own hearts [in order to appreciate Highsmith].”

Toward the end of the evening, Weil asked the panel for insight into the reasons for Highsmith’s deep anti-Semitism, which she was quite vocal about on several occasions. Wolitzer commented that the reality of Highsmith’s bigotry was a “definite failing” and although it is not evident in her writing, it is still “grotesque” and must, therefore, be acknowledged.

It is only since the release of the 1999 adaptation of her novel “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” an Anthony Minghella film starring Matt Damon in the title role, that Highsmith’s contribution to American literature has begun to gain attention.

“She was a hugely neglected writer,” Weil noted, “but I think more and more there is a recognition that she is one of our great American writers.”

More information about Highsmith’s life and work can be found by accessing: wwnorton.com/catalog/featured/highsmith/home

We also publish: