Playwrights finally take on Guantanámo detentions

In October 2001, a young man named Jamal al-Harith—an Internet Web site designer in Manchester, England—went on vacation to Pakistan.

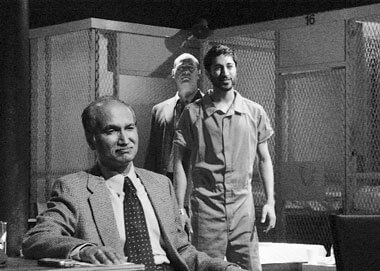

“I went from Manchester to Pakistan and ended up in Guantánamo, can you believe it?” he says—through the lips of an actor named Andrew Stewart Jones. “Yes, I went to Pakistan. Well, if that’s my crime then you’ll have to arrest plane-loads of people.”

The story of how he got to the American detention camp in Guantánamo Bay—captured en route in Pakistan by gun-toting Afghans and turned over by them to the Taliban, who took him to Afghanistan, questioned him, kicked him around as a Brit, put him in isolation, then released him into the general population when the bombing started—is also told in Jamal al-Harith’s own words in “Guantánamo: ‘Honor Bound to Defend Freedom,’” the blistering Tricycle Theatre production that comes to New York while still a sellout on London’s West End.

Nicolas Kent, founder/director of northwest London’s gutsy 11-year-old Tricycle Theatre and co-director of this collage of hard testimony about the base in Cuba where the United States is still holding some 600 “detainees” without benefit of hearing or counsel or anything resembling due process, compares his company’s theatrical technique to the WPA’s Living Newspaper in our own country’s New Deal days.

But he calls it Tricycle’s “long tradition of doing verbatim or tribunal plays” — starting in 1993 with a dramatization of the report of Lord Justice Scott on the British arms-to-Iran scandal (“much like your Oliver North hearings”) in which Margaret Thatcher was played by Sylvia Syms, who may be loved and remembered from dozens of British films, not least opposite Lawrence Harvey in “Expresso Bongo.”

The verbatims in “Guantánamo”—which has its press opening August 26—are those of a handful of detainees or former detainees, a couple of their fathers, some friends, attorneys, a few officials and a smidgen of remarks from Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

As when, at a press conference, asked if he has determined which detainees are al Qaeda and which are Taliban, Rumsfeld replies: “ ‘Determined’ is a tough word. We have determined as much as one can determine when you’re dealing with people who may or may not tell the truth.”

The same question— are the people in your case histories telling the truth?—was put to Kent and his young co-director, Sacha Wares, by this journalist.

“We don’t know,” she replied. “But a trial would have determined that”—and of course Guantánamo has only begun to respond to the long deferred federal court ruling insisting that due process proceedings be undertaken.

When Jamal al-Harith repeatedly ripped off his wristband at Guantánamo (“… in concentration camps they were given tattoos, and now they’ve given us these”), he was, he says, put in isolation for four days.

“There was nothing in the isolation cell except bare metal—built like a freezer, a.c. system blowing through cold air for 24 hours, so it turns into a freezer box … a fridge. I had to go under the metal sheet because the cold air was blowing in. I tried to go to sleep but you can’t because you’re just shaking too much.”

Jamal al-Harith, a British citizen born in Jamaica, raised in Manchester, is now in his late 30s.

“He’s extremely tall,” Wares said at 45 Bleecker Street one afternoon last week. “Lost an enormous amount of weight in that freezing isolation chamber. Has an amazing sense of humor. Wry. Very elegant. Very willing to talk. And very angry at what happened to him.”

One by-product of al-Harith’s ordeal is that his marriage, which produced three children, has ended.

“We know there’s torture,” Kent said. “What happened in Guantánamo alone is a form of torture.”

Had Tricycle sought any response from the authorities, U.S. or British?

“We tried to talk with both administrations,” Kent replied. “Had an e-mail conversation with [Cold Warrior and, until quite recently, Pentagon advisor] Richard Perle. It ended up with him saying: ‘I trust you’ll understand my skepticism about this project.’”

With a straight face, Tricycle’s peddler-in-chief added, “I’m expecting Mr. Perle will come to the Republican Convention. There’s a reserved-seat ticket [to ‘Guantánamo’] waiting for him. We don’t want to disenfranchise anyone from seeing this play.”

Sacha Wares, slim, pretty, going on 31, born in Nottingham, is the daughter of a teacher. Nicolas Kent, born in London “much too long ago to remember the date,” is the son of a British mother and a businessman father who was a refugee from Nazism.

Kent’s 240-seat Tricycle Theatre, at 269 Kilburn High Road, doesn’t just do this kind of stuff. It has hosted the British premieres of “The Great White Hope”; “Ain’t Misbehavin’”; “The Amen Corner” (by James Baldwin); “The Dwarfs” (by Harold Pinter); “Sorrow & Rejoicings” (by Athol Fugard) and four of the plays of August Wilson.

“Guantánamo has been a very big thing in the British newspapers for the past two and a half years,” Kent said. “We knew much more about it than Americans did. People shackled, chained, goggled, hooded. Ten British nationals, all facing the death penalty.

“I thought someone could do something like a wonderful opera about this. What Peter Sellars, for instance, could do with men in orange [prison] uniforms. So I approached the Royal Opera, but no one there was interested. Then I approached David Hare, who had done a verbatim play about the privatization of British railroads. He rang up Gillian Slovo, the novelist daughter of [famed anti-apartheid radical] Joe Slovo and Ruth First [activist killed by a parcel bomb in 1982].

“Gillian said: ‘I’d love to do it, but I’m just publishing a book and don’t have time. But I might do it with a friend.’ “

That friend was ex-journalist Victoria Brittain, a research associate at the London School of Economics and patron of Palestine Solidarity. Together, Slovo and Brittain conducted the interviews and shaped the collected raw testimony into a script for theater.

But first the few now-released detainees had to be interviewed.

“Nobody wanted to talk,” Kent said. “The press was besieging them. Eventually, with the help of Corin and Vanessa Redgrave, both of whom have been running a Guantánamo Human Rights Commission, we were able to set up interviews in London, Birmingham, and Leeds.

“Eighteen interviews, conducted in 14 days in late March and early April of this year. Then two weeks, roughly, to write the play, while Sacha and I cast it and designed it…”

“Blind—without a script,” Sacha Wares added.

The play opened May 20 at the Tricycle, and on June 16 moved to the New Ambassador’s Theatre in the West End, where it is to keep running into September.

One of the detainees’ lawyers, an articulate woman named Gareth Peirce (played here by Kathleen Chalfant, who else?), telephoned Michael Ratner, the Greenwich Village resident and downtown New York lawyer whose Committee for Constitutional Rights led the battle to throw light and justice onto Guantánamo from this end. Ratner, in turn, called Alan Buchman, who runs Off Broadway’s Culture Project and the 45 Bleecker Street that houses it.

“So you can say that Michael Ratner is the midwife in all senses of the word,” Kent acknowledged.

Last question: Whereby does Tricycle get its name?

“A very long story that doesn’t have a punch line,” Kent said..

“Guantánamo,” on the other hand, has too many punch lines, none of them funny. Well, that’s not true. There’s a bit in there about a poor slob of a British police officer trying to take fingerprints, and botching up the job, that reads like a Marx Brothers farce. But apart from that…