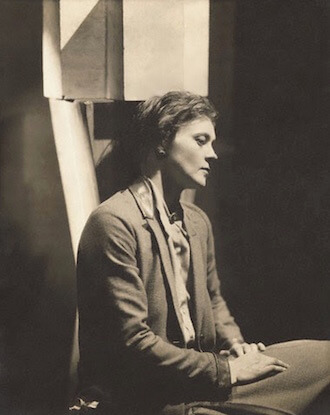

Romy Nordlinger as Alla Nazimova in her one-woman show, “Places,” directed by Katie McHugh, at 59E59 July 21-30. | DAVID WAYNE FOX

After seeing Russian-born actress Alla Nazimova in Ibsen’s “Ghosts,” both Tennessee Williams and Pauline Kael declared that she gave the greatest performance they had ever seen. For that reason alone, Nazimova (1879-1945) — known today for the most part only as the eccentric, outrageously flamboyant silent screen star of an outre version of Oscar Wilde’s “Salomé” (which she produced and co-directed and virtually ruined her) — should be remembered. To that end, actress Romy Nordlinger has written a play about her, “Places,” which opens July 21 at 59E59, directed by Katie McHugh.

Ken Russell’s 1977 film “Valentino” really did Nazimova a disservice, with Leslie Caron hamming it up ferociously in an obnoxiously hollow caricature of this great artist. The real Nazimova and her special voice fortunately can be experienced in three films in particular. Actually a rather plain woman without all the makeup and gorgeous costumes, she ironically played the touching mother of two among the handsomest of leading men — Robert Taylor in “Escape” and Tyrone Power in “Blood and Sand.” But it’s her glowing recitation of the inscription on the Statue of Liberty in the patriotic “Since You Went Away” that may very well be her most memorable celluloid moment — so incredibly relevant in her own life and resonant today given the Trump regime’s harsh attack on America’s immigrant tradition.

Nordlinger told me that her total immersion in Nazimova began three years ago when she was approached by Mari Lyn Henry of the Society for the Preservation of Theatrical History.

Romy Nordlinger tackles Nazimova, a towering, undeservedy obscure legend

“‘Darling,’ she said, ‘I want you to look at some of these actresses from the past because I want you to be researching and playing one of them,’” Nordlinger recalled. “A few were lovely but sort of WASPy and consumptive-looking, but then I came across Nazimova and I could not stop reading and thinking about her. I read everything about her and as many of her journal pieces as I could find, which had been hidden away.

“This play began as an excerpt and grew, and had to be cut down from hours to a one-hour play for this theater and for the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, who have invited me to do this over there, as well. As a writer you have to encapsulate but I give a very good overview of her life, not a biopic as it’s very much about her soul and what she was passionate about.

“It’s an absolute crime that she’s been so forgotten and I’ve become quite vociferous about that. My play has also evolved because it’s multi-media now. I needed this homage to be visual as was she, and it just lends itself to the look of those grainy black and white films, so far out but evocative and just gorgeous work. I don’t have the violet eyes that she was known for, but she once said, ‘I am neither tall nor short, ugly or beautiful, fat or thin, man or woman. I am what the part demands from me.’ And that was what she was about.”

Nazimova’s early years were difficult in the extreme, Nordlinger explained.

“She was an acclaimed violinist and a prodigy, but her father broke her arm because of her fame. She was a prostitute to get herself out of that situation before she joined Stanislavsky and his Moscow Art Theater. She made her American debut in 1906, in ‘Hedda Gabler’ and went on to earn the Shuberts millions. By 1917, she was earning $13,000 a week, the equivalent of $350,000 today. There was even a Broadway theater named for her, the Nazimova, on 39th Street, and I wondered why I had never heard of it. It was because she was a lesbian and a woman and way too powerful. The men had to sweep her under the carpet and she was erased, which was a disgrace.”

Unashamedly out, her lovers included Eva Le Gallienne, Dorothy Arzner, Mercedes de Acosta, Oscar Wilde’s niece, Dolly Wilde, painter Bridget Bate Tichenor, and her longtime companion, Glesca Marshall, whom she was with from 1929 until her death. Jean Acker and Natacha Rambova, both wives of Rudolph Valentino, were also involved with her and, as Nordlinger said, “She called Acker ‘my last faithful lover, who hid away my autobiography and tried to lock us both in a closet with it.’ Nazimova sort of pushed both women into marriage with Valentino and says he was overwhelmed by these voracious, volcanic women: ‘Imagine being known as the world’s lady killer when in reality the ladies killed him.’”

Nordlinger said that there was one man who had Nazimova’s heart, Charles Bryant, with whom she had a “lavender marriage” for 10 years. For him, she divorced her husband, actor Sergei Golovin. Bryant surprised her a few years later by marrying 23-year-old Marjorie Gilhooley. When the press discovered that he had listed his status as “single” on the wedding license, they brewed up a scandal regarding Nazimova’s deceptive relationship with Bryant that really damaged her career.

“They used to call the girls who hung out at the Garden of Allah, the hotel she turned her Sunset Boulevard mansion into — after she lost her money producing films like ‘Salomé’ — Gillette Girls, because like the razor, they sliced both ways [laughs]. The hotel was an enclave for movie stars, writers, and artists and a place of total sexual and intellectual liberty. It was torn down in 1959 and a Chase bank and McDonald’s now stand in its place.”

Nordlinger counts Nazimova expert Martin Turnbull as a big source and supporter.

“If there’s any foremost scholar on Alla, it’s him. He has the Alla Nazimova Society, as well as a site devoted to the Garden of Allah. He also has a series of six novels, the Alla Nazimova murder mysteries, and I was so nervous about introducing my play to him. But he said, ‘You got that right,’ and put up a teaser on his Alla site, which he said got more hits than anything. So maybe she’s not quite that forgotten.”

Amazingly, in 2015, Nazimova’s trunks were discovered in a house in Columbus, Georgia, containing treasures like the iconic pearl encrusted wig she wore as Salomé, a costume that was cut from the film, a jacket from “The Cherry Orchard” (1928), a headdress from “The Good Earth” (1932), and a shawl from that production of “Ghosts,” which drove Kael and Williams crazy, inspiring him to become a playwright. The house had been the residence of Glesca Marshall, Nazimova’s sole heir, and Marshall’s subsequent partner, Emily Woodruff.

“The wig is now the property of this elderly only living relative of Nazimova’s, a rich woman who’s a Republican and anti-gay. Martin feels that if he could find some legitimate institution that would really preserve it, she would let it go, but we don’t really know who to turn to.

“Alla was very depressed later in life because, yes, she was exotic and flamboyant, but she also introduced Chekhov, Strindberg, and Ibsen to the American public, had starred in the premiere of O’Neill’s ‘Mourning Becomes Electra,’ and was Stanislavsky’s progenitor. It seemed that she could never do anything that captured her soul, and very few people attended her funeral in 1945. Personally, when I am able to share a real a story of the human condition, that’s when I feel most alive. The struggle, the beauty, and the horror of it all is what kept her alive and what I relate to most about her.”

Raised in Richmond, Virginia, Nordlinger went to the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.

“Our core classes were taught by Camille Paglia, who for four years taught me the arts, history, Shakespeare, sex roles, and really helped form my thinking. Feminists dislike her intensely because she looks at things from an Apollonian perspective versus Dionysian: if women were left without men’s needing to sublimate the fact that they can’t inherently have babies, we would still be living in grass huts.

“My mother, Zelda Nordlinger, was a famous feminist and president of the National Organization for Women [Richmond chapter]. She was very strong, and as a kid I was constantly at rallies. My father was devoted to her and he’d say [laughing], ‘I know, Zelda, it’s testosterone.’ Because she would beat it into his brain that the main problem with our culture is testosterone, the male urge to kill. People were always trying to drive us off the road because of her abortion work. At a time when women weren’t doing anything, she read Betty Friedan’s ‘The Feminine Mystique’ and had been a pixie model — when they used to hire short models — to get out of a bad marriage. Like Nazimova, she had gone through disturbing things in Greenville, South Carolina. Her brother was exalted while she was shunned, and if she showed any evidence of thinking she was told to be quiet. So that rebellious part of me is from Zelda.”

Nordlinger concluded by noting just how timely her new play is.

“The last line of my play is ‘As we desperately scratch away shadows that that are closing in on us, dividing us once again, break that down!’ When I wrote that, I had this feeling that we were going into this post-Weimar kind of place in our country, but didn’t know how far it would go. There are lots of plays in reaction to Trump, and this story was strangely apropos. She tapped on my shoulder, ‘Tell my story now!’”

PLACES | 59E59 Theaters, 59 E. 59th St. | Jul. 21 & 29 at 8:30 p.m.; Jul. 22 at 6:30 p.m.; Jul. 23 & 30 at 4:30 p.m. | $15 at 59e59.org