The Metropolitan Opera has scheduled five Donizetti operas this season — two comic gems, “L’Elisir d’Amore” and “Don Pasquale,” and the Tudor Queen Trilogy as a vehicle for Sondra Radvanovsky. The Metropolitan completed the trilogy with the company premiere of Donizetti’s 1837 opera “Roberto Devereux” directed by Sir David McVicar (who also helmed “Anna Bolena” and “Maria Stuarda”), and Radvanovsky as Queen Elizabeth I seized another crown as her third monarch this season.

The aging Elisabetta in “Roberto Devereux” is in many ways the most demanding of the three queens — possibly more difficult than the title role of Bellini’s “Norma.” (Beverly Sills said the part took 10 years off her career.) It requires command over a wide vocal range from growling chest tones to brilliant coloratura, jagged multi-octave runs to seamless legato, and angry mid-range declamation contrasted with ethereal pianos. Like Norma, it demands an encyclopedic emotional range from raging jealous tigress to pathetic old woman.

Radvanovsky’s voice is an aural mixture of the ugly and the beautiful that can alternately or simultaneously thrill, repel, and captivate the listener. Pitch control and vibrato can be variable. The brilliant metallic edge on the tone (“squillo”) either sends tingles up your spine or hurts your ears. You love her sound or hate it — but you are not indifferent. The nature of Radvanovsky’s voice is that it thrives on extremes: the very loud, the very high, or the very soft. Anything in between is less interesting. When the music is hard, she takes flight but the easy lyrical stuff can be earthbound — tonally plain and lacking elegance.

Sondra Radvanovsky earns her triple crown with “Roberto Devereux”

Opening night reportedly found the prima donna soprano, tenor, and baritone in subpar vocal form. By the second performance on March 28, everyone had settled in and there was a lot of exciting high-powered vocal synergy going on. Radvanovsky’s performance level can vary over the course of a run or even in one evening. After an unsettled opening cavatina studded with either vague trills or out of control vibrato, she slowly took command in the cabaletta. From there, she built a thrilling arc to the furious second act trio finale where the queen’s jealousy provokes her to condemn the much younger man she loves. The thrilling out-of-nowhere forte high notes and disembodied floating pianos are familiar from her earlier queens but the fierce low chest notes are new. Elisabetta’s final aria “Vivi ingrato” lacked the vocal beauty of a Caballé but the slightly hollow, veiled dark timbre suggested the emotional desolation of the elderly monarch. I liked the majestic moderato tempo for the “Quel Sangue Versato” finale, though once again Radvanovsky lunged at a climactic high D which she could not sustain. If you can’t hold it, why go for it?

McVicar and Radvanovsky follow history more faithfully than the librettist by portraying Elizabeth as a grotesquely painted and physically debilitated old woman, though the music suggests a vigorous, powerful middle-aged queen. Radvanovsky wielded her walking stick with a vengeance, limped when she remembered to, and executed the now de rigeur business of doffing her curly red wig in the final scene to reveal short white hair. I frankly wish she had focused less on surface grotesqueries and more on exploring the conflicted emotional life of the character. With a hard-to-control vocal instrument, Radvanovsky concentrates more on controlled vocalism than textual nuances and on acting often generalized or stilted.

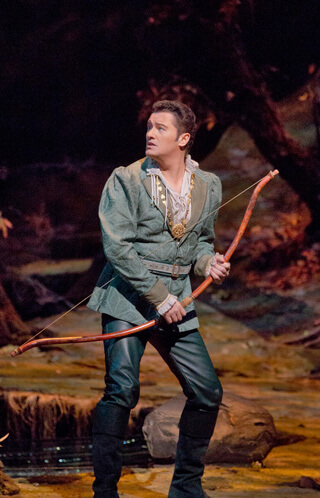

In the title role of the Earl of Essex, an uncharacteristically fiery and engaged Matthew Polenzani put aside his usual self-effacing manner, exuding virile passion in his confrontations with the other three protagonists. Polenzani’s lyric tenor took on a sunny vibrant color while his phrasing displayed his trademark refinement and elegant style. However, a lingering indisposition (one that affected him on opening night and has taken him out of subsequent performances) caused him to tire by the end of the Act III prison scene.

Mariusz Kwiecien as his friend-turned-enemy Nottingham concentrated more on smooth legato phrasing, which suits his warm lyric baritone better than brute force. A few pushed climaxes turned hollow and sagged flat but there were no cracks as was reported on opening night. The friendship between Nottingham and Devereux is presented as being unusually affectionate and physical — one wondered whether it was his wife’s or his best buddy’s betrayal that provoked Nottingham’s deadly jealousy.

As his love-torn wife Sara, ElÄ«na GaranÄa returned to the Met after a long absence. GaranÄa’s voice is now one size larger — Dalila, Eboli, and possibly Amneris seem plausible future assignments. The Latvian mezzo possesses impressive ease at both range extremes, venturing up to soprano high C. Her tone is seamless and under total control, and her manner was also coolly commanding — too much so for this vulnerable, melancholy character.

With all this vocal quality onstage, it was dispiriting to encounter a dull routinier in the pit. Maurizio Benini’s four-square tempos were motoric when they weren’t plodding — no spring in his rhythmic attacks and minimal shaping to the accompaniments.

McVicar’s production is probably his best effort in the Donizetti trilogy. The director designed the unit set consisting of a movable paneled rear wall with arched portals surrounded on three sides by tiered galleries. On either side of the central door are inlaid figures of the Grim Reaper and Father Time. These serve as a memento mori for the old monarch — along with the marble tomb of Queen Elizabeth that is wheeled out at the beginning of the evening during the overture and for the final tableau. A huge Renaissance clock takes up most of the back wall, also suggesting the inexorable hand of time and fate.

The set also evokes an Elizabethan playhouse, which McVicar exploits by having the chorus onstage throughout the action. They observe the soloists and even applaud their entrances as if they are actors in a play. Though any royal court was essentially a gilded fish bowl with the monarch as big fish/ star performer, the tired play within a play conceit comes off as contrived and distancing rather than illuminating.

“Roberto Devereux” is a singer’s opera. If Radvanovsky continues to command her voice and the stage, if Polenzani recovers his vocal health, if Kwiecien doesn’t force his velvet baritone and GaranÄa occasionally thaws her ice-queen manner, then expect wonderful evenings in the house and a glorious afternoon at the Met in HD transmission on April 16.

Moving from historical tragedy to bucolic comedy, “L’Elisir d’Amore” was revived as a vehicle for Vittorio Grigolo, a favored artist of the current management. Bartlett Sher’s production looks sweet but plays sour –– turning the illiterate country bumpkin Nemorino into a moody country poet adds nothing and takes away so much that is distinctive and comedic in the role. Changing Belcore’s regiment from local soldiers to the occupying Austrian army during the Italian Risorgimento seriously distorts the tone of the work. They sexually harass the local women and actually gang up to gut punch Nemorino during the Act I finale. The onstage scene change during the Dulcamara/ Adina duet in Act II just looks inept.

Anyone who has heard Grigolo interviewed on the Met radio intermissions knows that he can be quite scatterbrained, unpredictable, and manic offstage. I had hoped he would bring the “matto” (crazy guy) energy back to Nemorino along with the romantic persona this production wrongly insists upon. Unfortunately, Grigolo’s interpretation turned out self-indulgent and mannered. He delivered much of his music and acting to the footlights, playing to the audience rather than the other characters. His sunny, lean lyric tenor, so perfect for lyrical Donizetti, seemed to dwell on each note and word rather than carve out legato phrases and arching musical lines. The shape of the music was lost among all the fussy nuances. Grigolo begged the audience for an encore after a rather overwrought rendition of “Una Furtiva Lagrima” –– but he did he did not receive the go-ahead. Grigolo’s Des Grieux in “Manon” last year revealed a dynamic sensitive artist. This outing reinforced the fact that he needs directorial and musical discipline even in repertory that should be home territory. Still, he was giving a “star” performance –– just not a very good one.

Aleksandra Kurzak as the saucy, willful Adina, with her dimples, round cheeks, and saucer eyes, was the very picture of the country coquette. But Kurzak sounded prematurely old with a scrappy, edgy sound that would not center on the pitch. What happened to that pearly-toned, pitch perfect Gilda of not so long ago?

Adam Plachetka was a virile Belcore with tonal body throughout the range. Alessandro Corbelli’s Dr. Dulcamara felt routine, with a dry juiceless buffo tone. Enrique Mazzola conducted a very fast, uninflected first act but settled in for a more relaxed, shapely second act.

The last performance of the “Elisir” run on April 7 proved a happy corrective to all that was wrong with the opening performances. Even Kurzak sounded fresher and hit most of the pitches correctly –– though her physical charms still outweigh the vocal.

Guatemalan tenor Mario Chang, late of the Lindemann program and now resident in Frankfurt, took over as Nemorino. Diminutive with big dark eyes and round cheeks, he brought an endearing underdog persona back to the role. Vocally Chang reminded me of early career José Carreras, with a darkly burnished Spanish timbre blended with the melting lyricism of the young Ramón Vargas. He mostly sang loudly yet did manage soft pianos in a fervent rendition of his big Act II aria.

Pietro Spagnoli, who took over from Corbelli as Dulcamara, was wonderfully wily and spontaneous with a juicy bass-baritone sound. Joseph Colaneri conducted with more swing and melodic shaping than Mazzola, and the infectious mood translated over the footlights to the audience.

Amore Opera, the successor to the beloved Amato Opera, did local audiences a favor by resuscitating Donizetti’s rare tragic opera “Poliuto.” Presented at the charming Sheen Center on the Lower East Side not far from the Bowery (the original site of the Amato Opera), the scrappy, ambitious company did surprisingly well with this three-act grand opera in the heroic mode. Based on a tragedy by Corneille, the opera fictionalizes the life of the Christian martyr St. Polyeuctus (a fact that caused the court to ban the work in Naples –– it was never performed in its original form during the composer’s lifetime).

The Roman consul Poliuto, stationed in Mytilene in ancient Armenia, has secretly converted to Christianity. His wife Paolina is torn between her loyalty to her husband and to her first love, General Severo, who has returned to Mytilene with orders from Rome to exterminate the Christian heretics. Poliuto is torn between his sacred love of God and his profane jealousy –– spurred on by the evil pagan priest Callistene –– of his wife’s supposed infidelity. After Poliuto is condemned by Severo after revealing his Christianity in the forum, Paolina comes to Jesus and decides to stand by her man even if that means being devoured by lions. The two march into the arena to the uplifting strains of a martial duet. The solo voices were in general good, though all the singers could only sing loud when they had to sing high.

Modena-born tenor Paolo Buffagni (he shares the birthplace of Pavarotti), sang Poliuto in a thick, grainy-toned tenor that had good Italian metal in it but lacked suppleness and grace. A dignified actor with clear native diction, Buffagni did not attempt the interpolated high notes that Franco Corelli took in the famous 1960 La Scala pirate recording with Callas.

As Paolina, the lovely Jessica Sandidge unfurled a vibrant, richly colored soprano that opened up on high. Baritone Robert Garner was a rock-solid Severo who commanded his music and the stage with authority but also some sensitivity when required.

Daniele Tirilli led an idiomatic account of the score but was dealing with a large, somewhat unruly volunteer orchestra. I wondered if perhaps a smaller group of more professional players in a chamber reduction would have served the music better.

Similarly, less might have been more with Richard Cerullo’s two-dimensional painted scenery. The sets often crowded the shallow stage. A subtly redressed amphitheater unit set with pillars and arches would have provided more sophisticated stagecraft with less clutter.

Amore Opera returns with “Rigoletto” (May 20 to 29). This lovable company in its comfortable new home provides exposure to talented local singers and needs your support (amoreopera.org/comingsoon).

More Donizetti comes our way on May 4 when Opera Orchestra of New York revives itself from near extinction with a concert performance of “Parisina d’Este” at the Rose Theater starring Angela Meade in the title role (jazz.org/events/t-5600). Viva Donizetti!