By comparison to this year’s utterly misfired “Traviata”, Michael Mayer’s Rat Pack-era, Vegas-set “Rigoletto” (April 26) seemed less offensive — though still there are aspects of the visually neon-lurid story that make no sense. If “the Duke” is a famous headliner, how do Sparafucile and Maddalena not recognize him? Has no one at the hotel or church wondered why the teenage Gilda is not attending school? Does the titular jester-as-Rodney-Dangerfield really believe in curses?

In their blatancy, Christine Jones’ sets and Susan Hilferty’s costumes become wearisome. Truly obnoxious — and, like the frequent yellings from the stage, profoundly unmusical — are the slangy, wannabe snarky Met titles, designed for those who can’t or won’t listen to the music. Is that Peter Gelb’s target audience? That said, the Met is doing something right: a youth-aimed “party night” got hundreds of younger people in to see (maybe even to hear?) Verdi’s wonderful score, and they seemed to be having an excellent time.

Surely everyone enjoyed the evening’s soprano and tenor. Gilda can be a striking, high-wire Met debut role. Gianna d’Angelo, Mariella Devia, June Anderson, and Sumi Jo all pulled it off, and so, splendidly, did Italian-born Rosa Feola, after doing the part in Naples, Munich, Chicago, Zurich, and elsewhere. Feola made the naive girl both appealingly vulnerable and understandably chafing at her father’s evasions and restrictions. She made much of the text and sang in a limpid, well-projected lyric-coloratura that could ride the orchestra when necessary. Brava! She seems like a major addition to the company roster.

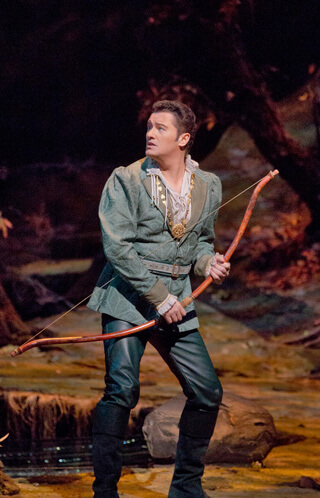

Matthew Polenzani’s Duke is less the boy band idol (over)played by Vittorio Grigolo than a slightly aging roué trying to re-spark his youth. His cocaine-fueled Act Two cabaletta was one place where Mayer’s ideas worked. Polenzani sang beautifully, with wonderful phrasing and expertly layered dynamics allowing him a wide expressive range.

With his somewhat blunt voice, short on legato in top phrases, George Gagnidze isn’t a great Rigoletto, but by current standards he’s quite good; certainly preferable in terms of pitch to Zeljko Lucic. He gave the role in Mayer’s concept a good shot and sang movingly in quieter passages. The end — with Rigoletto comforting Gilda, who’s dying Tarantino-style in a car trunk —just didn’t come off emotionally. Well as Feola sang here, both artists seemed uncomfortable. Emotion got sacrificed for a cool image.

Low F’s in place, buzzy-timbred debuting bass Dimitry Ivashchenko made a decent enough Sparafucile; for once, one missed the sleazier Stefan Kocan, in the one Met role he’s done superbly. Romanian mezzo Ramona Zaharia (Maddalena) both sounded and looked duly sexy. In Stefan Szkafarowsky, we heard a veteran, loud but vocally grizzled Monterone. The bass would be effective in many character roles but — though few opera companies seem to grasp it — this isn’t that kind of assignment. As with Paolo Albani in “Simon Bccanegra,” Monterone needs someone who might plausibly also sing the opera’s title role. Plus, the “sight gag” styling of the enraged count as an Arab sheikh — only in New York! — and the idea that one presumably helping to bankroll the casino would be shot amidst a crowd of witnesses are among the sillier aspects of Mayer’s shallow staging.

Disturbingly, few of the comprimarios were satisfactory; the mysteriously omnipresent Eduardo Valdes sounded downright unpleasant as Borsa, and Jeongcheol Cha, though he acted thoughtfully, was too tonally diffuse as Marullo. Only Samantha Hankey’s Marilyn-lookalike Countess Ceprano really distinguished herself vocally. Like many “legit theater” imports, Mayer doesn’t know how to deploy an operatic chorus, and though they sang well, their scenes fell flat dramatically. Nicola Luisotti conducted squarely; several times key soloists seemed not in synch with the pit.

On May 9, Hunter Opera Theater, in association with American Opera Projects’ ongoing off-Broadway festival of stagings, gamely mounted 1998’s “Patience and Sarah,” the first explicitly lesbian-themed opera. With very tuneful tonal music by Paula M. Kimper and a solid libretto by Wende Persons constructed from short scenes, the opera follows the popular 1971 historical novel by Alma Routsong (writing as Isabel Miller). Based on pioneering early 19th century Connecticut watercolorist Mary Ann Wilson, the economically comfortable Patience White takes up, despite familial opposition, with the working class, somewhat scandalous Sarah Dowling, raised as a boy — but not before Sarah, as “Sam,” wins the attentions of a roving book peddler, the married gay former parson Daniel Peel. Eventually the women head west to find freedom together — even winning a blessing from Patience’s straitlaced brother Edward.

It’s a same-sex wish fulfillment story that must have been very welcome in the days of death-curtailed lesbian narratives such as 1967s “The Fox” and remains entertaining today. I missed the opera’s premiere staging and was happy to encounter it now, well led by David Fulmer if somewhat summarily directed by Susan Gonzalez in creative projected folkish designs by Monica Duncan and Lara Odell. Kimper’s vocal writing may not challenge the ear but the harmonic patterns and tessitura are not simple.

Katherine Robinson’s fine ”juicy lyric” soprano, sounding career-destined, handled Patience’s music quite beautifully. Convincingly baby butch despite rather feminine make-up for a would-be 1820s farmhand, Katarina Wilson (Sarah) fielded a sparky high mezzo with a tight vibrato that helped it carry. Clarity of words wasn’t the performance’s strong suit; for once I wished for surtitles. The other student singers showed commitment and still-developing talents, with Paule Aboite (as Sarah’s mother) a standout for characterful timbre and verbal clarity. Brandon Snook, a professional, deployed a useful tenor with skill and variety as Edward. Aptly, cast and creators were warmly received.

The next night, Zankel/ Carnegie hosted a lovely concert by Jonathan Cohen’s first-rate baroque ensemble Arcangelo with soprano Joélle Harvey — with whom they’ve recorded — as guest soloist in Handel’s blissed-out-on-Creation “Nine German Songs,” dating from the mid 1720s. Written with melodic hints of Handel’s contemporaneous operas, these pieces to texts by Barthold Heinrich Brockes still get few performances live, though they’ve been recorded very well by Edith Mathis, Arleen Auger, and Julianne Baird. Harvey’s Zankel performance was distinguished by stylish, apt decoration — often but not always upwards cadenzas, a nicety which the instrumentalists also observed. Her dark-flecked, clear soprano sounded fresh — and, as one often observes, even more fresh after her first re-entry following a pause. Musically in control, she might have dug more crisply into the German texts — but a lovely performance nonetheless. The faster numbers got and sustained very swift tempi.

All the Arcangelo members — Cohen (harpsichord and organ), Georgia Browne (flute), Thomas Dunford (lute), Sophie Gent (violin), and Jonathan Manson (viola da gamba) — proved deft and eloquent, making the Handel continuo as beautiful as the Bach sonata and revelatory Buxtehude Opus 1 sonatas they played amongst the arias.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.