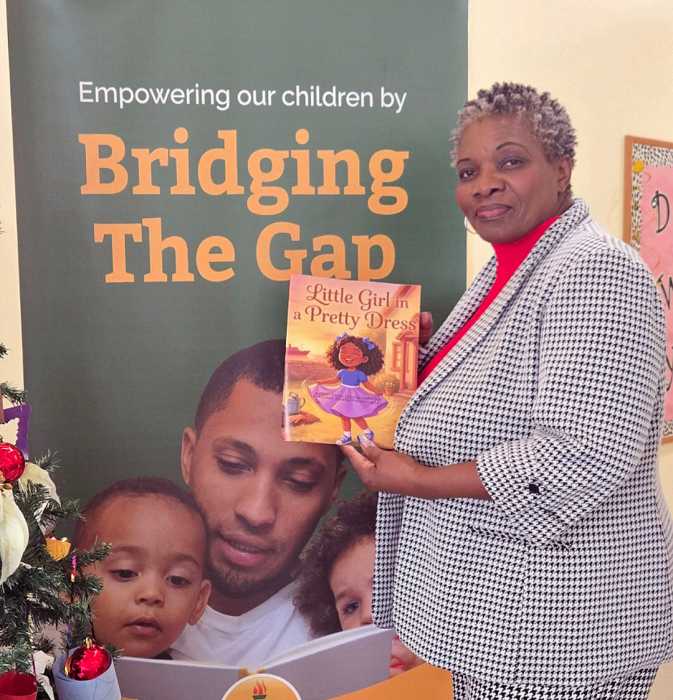

David Schachter and Geoff Edholm in Arthur J. Bressan, Jr.’s “Buddies.” | FRAMELINE RELEASING

It has been 33 years since the initial release of “Buddies,” the first feature film to depict AIDS. On June 22, the Quad Cinema is giving moviegoers a week-long opportunity to see a new 2K restoration of this classic of independent queer cinema. The film was written and directed by Arthur J. Bressan, Jr., who himself died of AIDS in 1987, less than two years after “Buddies” premiered.

The opening credit sequence features a print-out of hundreds of names of people who died from AIDS, a canny political framing on the emerging epidemic. The storyline has 25-year-old typesetter David Bennett (David Schachter) volunteering to be a buddy for AIDS patient Robert Willow (Geoff Edholm). He arrives at Robert’s St. Matthew’s Hospital room wearing a surgical mask and other protective clothing as an ominous sign indicates “isolation measures” for AIDS patients. Robert is asleep when David arrives, and upon waking greets him with, “Who the fuck are you?” before shaking David’s gloved hand — an inauspicious start to what will become a very tender friendship.

“Buddies” uses David as a device to draw viewers into the story. His naiveté about AIDS — he claims not to have known anyone with the disease — was certainly not unheard of back in 1985. As such, his character, who explains that he came out to his accepting parents and has been in a monogamous relationship with Steve (David Rose) for five years, provides a good contrast for the 32-year-old Robert. The patient, who has been sick for about nine months when David arrives, is an activist from California, whose parents disowned him when he came out. Unlike David, Robert believes in visibility, a lesson he will impart to his buddy during their three-month friendship.

Pioneering 1985 drama “Buddies” explored what an epidemic could teach

Bressan is a bit didactic in his screenplay, which has the men debating opposing points of view about being gay, but their conversations are never uninteresting. What’s more, they speak in terms both personal and political — and these scenes are careful not to insult either the well-intentioned work of people like David or the more radical queer perspective that Robert represents. When David talks on the phone to his mother (Libby Saines), he articulates what he’s learned from getting to know Robert, showing how his experiences have helped him think and grow.

“Buddies” features voice-over journal entries by David, who questions why he volunteered and considers how he’s changed. But better are the hospital bedside conversations David has with Robert about the fear, guilt, and regret both men face in the age of AIDS. A lovely moment has David asking Robert about how he would spend a single day if he were healthy. Robert’s answer is both poignant and political.

Another exchange between the men — in which David gives Robert pages from book of AIDS essays he is typesetting — is important but heavy-handed. The text consists of anti-gay rhetoric and Bressan zooms in on the page so viewers can read it. Robert becomes incensed, coughing, shouting, and eventually requiring medical attention, a too on-the-nose response to homophobia.

But even this scene is powerful. It emphasizes the attitudes that gay men — as well as lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people — faced back in that era. This episode provides a key contrast to David and Robert’s discussion of a pride parade they watch on a VCR in the hospital room. When David, who did not march, asks, “Why should I want the world to see me?,’ Robert emphasizes the importance of having a connection to the community. When David declines the opportunity to be interviewed by a newspaper reporter about being an AIDS buddy, Robert encourages him to change his mind, emphasizing the importance of having people with AIDS portrayed honestly.

“Buddies” is honest and heartfelt, its greatest qualities. This largely realistic portrait depicts issues that were critical at the time. One touching scene has David collecting Robert’s things from his apartment. David looks at photos of Robert with his lover, Edward (Billy Lux) — whom David resembles — and reads Robert’s letters. David even imagines himself replacing Edward in the photos, a fantasy suggesting the deep love that has developed between the two buddies.

As groundbreaking and heartwarming as the film is, Schachter’s lead performance is a stiff. The actor, whose only other film credit was in Bressan’s earlier film “Abuse,” lacks depth in conveying his emotions and is never as moving as his co-star. Edholm is stonger, especially as his character starts to feel and look worse. His big scene, where Robert exclaims, “I don’t want to die!” does not feel mawkish; his anguish is real. Sadly, Edholm, too, succumbed to AIDS, in 1989.

“Buddies” ends with an inspiring moment — how could it not? But its greatest power is how Bressan humanizes people with AIDS and tells a story that people needed to see — and still do.

BUDDIES | Directed by Arthur J. Bressan, Jr. | Frameline Releasing | Opens Jun. 22 | Quad Cinema, 34 W. 13th St. | quadcinema.com