Marian Seldes and Brian Murray peerless in evening of Samuel Beckett, Edward Albee

“Beckett/Albee” is such a wonderful evening of theater that even though it deals with such somber subjects as physical and emotional decay, the alienation of the spirit, and life’s incessant wearing upon the soul, one leaves the theater uplifted and enthusiastic.

Part of this is because both playwrights—Samuel Beckett and Edward Albee—are so accomplished at exploring the dark and fearful corners of the heart that most of us have created entire lives to avoid. They grab despair by the throat and have the courage to create real and challenging catharsis in the structure of their plays, however absurdist the situations.

Part of their success to due to the fact that both Beckett and Albee are masters of language, and the specificity with which they choose their words bespeaks an artistry sorely lacking in much contemporary playwriting.

The short works presented are all pieces that require the theater to give them voice.

I’m getting so tired of TV movies masquerading as plays and special effects children’s films pretending they’re musicals, that seeing work that acknowledges and embraces the abstraction of the theater and the patent falsehoods upon which it relies––artistically and metaphorically––is a true cause for rejoicing. On top of that, to see two such astonishingly wonderful actors as Marian Seldes and Brian Murray… Well, it doesn’t get much better than this.

The first act consists of three plays by Samuel Beckett. The first, “Not I” is a monologue in which Ms. Seldes’ appears to float in the dim light, draped in black so that only her mouth is visible—brilliant red lips on a china white chin. What pours forth from this mouth is an unrelenting diatribe, the cacophony of the disembodied mind replete with buzzing, false starts, and truncated arguments that are the subtext of existence. Lurking at the corner of the stage is an auditor, also draped, who simply hears what transpires. This thoroughly engaging play is at once beautiful and horrifying. It implies that we are nothing without our voice, but dares to look behind that voice at the fear, confusion, and chaos of our true, versus presentational, experience. Ms. Seldes’ remarkable technique carries the play, evoking more real feeling with just her voice than many actors can summon with a full mounting.

In the second play, “A Piece of Monologue,” Mr. Murray is a man clad just in “gown and slippers” at the end of his life, looking at death and responding with a dichotomous mass of rage and resignation. What is remarkable about this piece is that Beckett’s character does not so much speak the unspeakable as avoid it, naturally rendering what is unsaid even more horrible and more present. Mr. Murray gives a fine performance here, focused and present.

The third piece, “Footfalls,” will put you in mind of the cult documentary “Grey Gardens.” It is the cry of a woman, who today might be diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, plodding through her apparent craziness, yet at the same time deeply engaged in the search for order and meaning, as the delusions of her illness and the heavy thud of her feet beat into our consciousness. As with the other two pieces, this is a powerful quest, seemingly against all odds and without tidy resolutions.

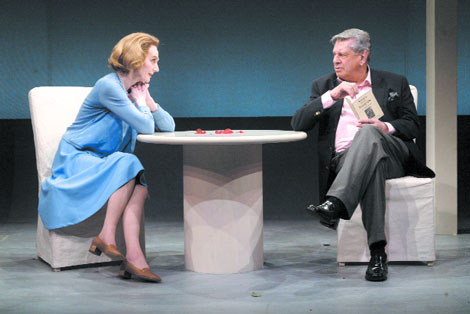

The second half of the evening belongs to Mr. Albee. “Counting the Ways,” by comparison to the Beckett pieces, is, at least on the surface, a comedy of manners. But as with “The Goat,” Mr. Albee acknowledges the conventions of comedy but uses them for his own purposes. The play is a series of stylized blackout sketches that each highlight one interaction between a couple who have apparently been together a long time. The quickness of the scenes sometimes makes the play feel even more stylized, and the brilliant direction by Lawrence Sacharow, who is responsible for all of the plays in this evening, puts Ms. Seldes in a series of extreme poses at the end of scenes, which provide a wry commentary between external appearances and internal strife in long-standing relationships.

Mr. Murray and Ms. Seldes are at their most charming and engaging in this piece, and the precision of their performances is so beautifully matched to Mr. Albee’s script that the result is a seamless and flawless examination of how love transmutes with time. Though not always happy, there is joy in the intellectual and theatrical integrity of this piece.

Much has been written about the influences of Beckett on Albee, and certainly in watching these four plays one can see echoes of similar artistic searches. Yet the differences between the two are equally compelling. While Beckett reaches into the purely absurd for his metaphors, Albee revels in the absurdity of everyday people. Taken together, and ranging in sequence from the most abstract to the most (nearly) naturalistic, these plays, on many levels, represent the most stimulating, pure, and thrilling theater in New York right now.