BY DAVID EHRENSTEIN | “I’m emotionally blocked, stupid in practical matters, and cursed with an isolating intelligence that’s worthless,” Gary Indiana self-disses roughly halfway through this improbably potent apologia pro vita sua. “I must have pretended my life was a novel, or a movie I was narrating as it went along.”

But to anyone who has read the works of this scathing social critic, cultural weathervane, and crime scene adept, he is in no way “cursed” or “worthless.” That he regards his life as a species of film or novel in progress is proof of his work’s inestimable value. For Gary is what post-structuralists call a “participant /observer” of la condition humaine, and he spares himself nothing as he regards the world that engulfs him with a wryly jaundiced eye.

And this is why the title of his latest tome converts the expected “can’t” to “can.” For while Gary Indiana, who has done everything from teach philosophy at the New School to co-star with Veruschka in Ulrike Ottinger lesbian avant-garde film spectaculars, wants love he knows he’d be a fool to expect to find it in a culture as bleak and soul-crushing as this one.

Gary Indiana’s brilliantly jaundiced eye is not just watching others

Born Gary Hoisington in Derry, New Hampshire, his adoption of “Indiana” as a surname suggests a desire to get right to the heart of the American character, which he pegs as entirely criminal in nature. He proves this point repeatedly in such pitch dark quasi-novels as “Resentment” (his 1997 take on Beverly Hills murder-brats Lyle and Erik Menendez), “Three Month Fever” ( his 1999 retracing of the path of Versace-targeting “spree killer” Andrew Cunanan), and “Depraved Indifference” (his 2002 go at the mother-and-son murder-for-profit team of Sante and Kenneth Kimes).

His unwillingness to bestow so much as a soupcon of “sympathy” on these craven creatures leaves the alleged insight of “In Cold Blood” in the dust, along with its shallow social-climbing author. Compared to Indiana, Capote is nothing more than a 10th-rate “sob sister” pimped by a credulous press into a latter day Dostoyevsky, while not up to the middlebrow pulp level of an Earl Stanley Gardner.

On a personal level the contrast between these two is even starker. While Capote brandished his “feminine” affectations as if they were some species of inner truth made outwardly manifest, Indiana is eminently practical about his insipient feyness — and what might be called its “market value.”

“There isn’t any roadmap to homosexual relationships,” he keenly observes. And the road he’s taken has been a hard one. His teenage years found him being used as a kind of sexual appliance — servicing others orally while getting nothing in return. Reaching adulthood, he served as an anal receptacle — but never an object of affection. And his matter-of-fact acceptance of this is truly heartbreaking — though Indiana wouldn’t dream of tugging at “heartstrings’ in the standard manner.

A kind of phantasmagoria set in New York and LA (“a city of false starts”), but with pit-stops in Boston, San Francisco, Havana, and Istanbul, “I Can Give You Anything But Love” finds Indiana confronting the awful truth that his love life is a sex life — at its most abject.

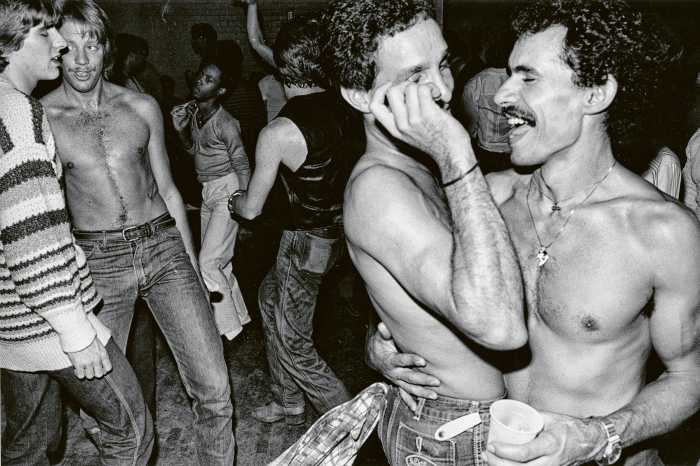

“I pick up a new person every night. This procedure is fraught with insecurity about my attractiveness. My willowy, fey look passed out of fashion a while ago when the androgynous template slowly butched up during the disco era, becoming the preset macho clone craze. I’m put off by the leatherman thing, handkerchief signals, big hairy chests, and mustaches. If the Tom of Finland types aren’t stupid as boiled okra, they give that impression in conversation. But there are usually some available persons in my acceptable range of maleness. Then it’s down to whether or not they see me in a similar light.”

Not quite as stark as “The Sex Factory,” his piece on gay orgies in the collection “Let It Bleed” (1996), it nonetheless vibrates with abjection — a state Indiana finds not exceptional but common.

Flickering in the half- light of these sullen sexual recollections, one finds the recurring figures of “Ferd” and “Dane” — friends (which is to say simply that they’re nicer to him than anyone else) who are never fully fleshed out as they would be in a conventional piece of writing. Here they’re simply points on the graph of what is less a memoir than what the French call a “recit” — or “account.” The primary practitioners of this form are French — Michel Leiris, George Bataille, Hervé Guibert — though they also have an American cousin in Dennis Cooper (most markedly in his collection of stories “Ugly Man”).

“The rapes seemed more ridiculous than tragic,” is Very Dennis. But it’s pure Gary, too. It typifies a text that recalls everything from the heyday of New York’s Mudd Club (where he held forth as a diseur) to Los Angeles, where for a time he lived in the same apartment building as neo-punk pop star Exene Cervenka.

“The shoot-out that turned the Symbionese Liberation Army into French fries had happened only twenty blocks north,” Indiana recalls, adding, “If I hadn’t been high at the time I would have been petrified.” But he’s never petrified. He is in fact eerily calm about it all. It’s how he’s gotten though life up to now, and he has no intention of changing.

“I clung to the sidelines, watching. I admired the club people. They weren’t dumb. They knew time was roaring past.”

But so did Gary Indiana. And rather than simply “clinging,” he writes about what those “sidelines” meant. Toward the end, he recalls an accident — his Volkswagen spinning out of control and crashing into the underpass of the Hollywood Freeway “somewhere between the Rampart District and Echo Park.” After “trudging down the dark road, thorough endless nothingness,” he finds a gas station, with no personnel present, and calls the police. When they arrive, “There’s a lot of rough language conveying their anger and disgust at my irresponsibility. There’s a pinch of homophobic ridicule, but not as much as I expected.” Eventually a tow-truck driver arrives. “You lucked out,” the driver tells him “on account you got the insurance. No insurance, you’d be spending the night in the holding tank.” And then the best part: “‘Plus you’re white’ the driver adds. ‘With cops in this town that’s a lucky plus.’”

Yes he may be “stupid in practical matters,” but at the last Gary Indiana is a very lucky guy.

I CAN GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE | By Gary Indiana | Rizzoli Ex Libris | $25.95 | 240 pages