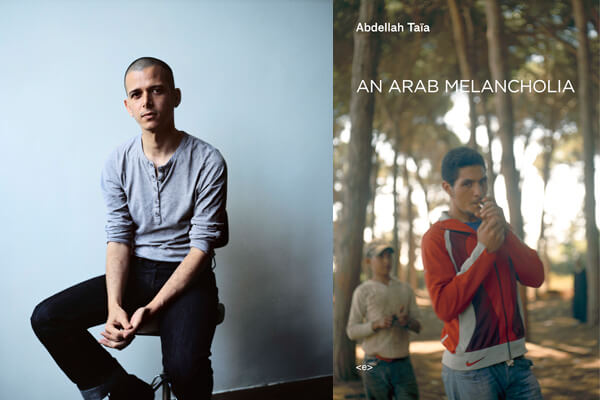

A Moroccan author living in Paris, Abdellah Taïa came out as gay publicly in 2006. His best known book, “Salvation Army,” was published that year, and his 2008 book “An Arab Melancholia” has just been released in an English translation by Frank Stock.

Taïa corresponded via email with Gay City News and discussed his interior life as a gay man, an Arab, and a Muslim.

MICHAEL LUONGO: We know you best from your previous book, “Salvation Army.” In that work, it is hard to know what is true and what is the novel. How much in “Arab Melancholia” is true, how much is false, how much is novel, how much is autobiography?

ABDELLAH TAÏA: I never ask myself these kinds of questions. I write because I have things to say, stories and some truth to reveal. I don’t care about fiction. I don’t write fiction. I write from my world, the interior one, the troubled one. I use what I feel, what I felt, in a literary way. And I mean by that constructing texts, fragments, shorts phrases, a specific rhythm. I really believe that the duty of any writer is to speak from his own world, to talk about it, to show it to the world. To be true with it.

Every time I get copies of my books, I feel that they are not books or novels or shorts stories. I feel that they are the continuation of the poor little Abdellah I was in my Moroccan hometown, Salé. Abdellah –– gay, poor, barefoot, clever, fighting, humiliated, but in the middle of a precise Arabic world. I write because this specific world inspires me, gives me the strength to go through many, many difficulties in order to build something with a meaning. A transgression. A poem. A tear.

ML: The novel begins quite violently, with the rape of the main character Abdellah by Chouaïb. Yet Abdellah also seems to have a crush on the aggressor. Why does the novel begin in this way?

AT: That’s the definition of love for me. We all have happy dreams about finding love. But, when we –– kind of –– find it, it’s always, always, a big violence. And not only a physical one. And not only a violence coming from the other we love. I am talking also about the violence coming from us, from me. Every time I was in love with a man, a big dictatorship comes out from me. In general, people do not say the truth about love. It’s certainly not something nice, sweet, calm. It’s the opposite of that. It’s wrestling, crying, being Machiavellian. Being so much alive because you are every day in war.

The first chapter of “An Arab Melancholia” talks about all this, defines what is love for me, and, at the same time, brings a specific geography of a poor Arabic neighborhood and what could happened to any Arabic boy who is effeminate or gay. Anyone could rape him and no one would come to save him. That’s what happens to Abdellah here. But, in the middle of this scene, Abdellah finds two ways to resist –– one, he demands that the character Chouaïb stop calling him by a feminine name, Leila, and if he wants to have sex with him, he should admit that he is a boy having sex with another boy; and two, he falls in love with Chouaïb.

ML: There is a theme you have here which is in your other work –– you are in love with a Western man who only treats you as a sex object, in this case, Javier in Paris, who, while you’re waiting says, “One more email, then we’ll fuck,” which breaks your heart. Can you comment on the sexual objectification of the Arab man in France and perhaps other parts of the West?

AT: I wrote this novel in 2008. I think that the world is now starting to change the way it sees Arabs, men and women. Thanks to the Arab Spring, a lot of things are not anymore the same for the Arab and for the Western people. The Arabs are rebirthing again. And this time with a political consciousness that the change will come from them and not from their dictators. The Arabs now are so much far from the West’s view of them. They broke this stereotype. Now the West should admit that it was also responsible for what was happening in the Arab world. The West supported so much the Arab dictators, and it took him a lot of time to see that the Arab Spring was something serious and not a one-day demonstration. The orientalist visions of the Arab world are now officially dead.

ML: In another case, in Paris, the main character is with Slimane, an Algerian, described as “more of an Arab than me.” What do you mean by that, and for the character, was being with an Arab in the West a sense of safety in a different way?

AT: Slimane is more Arab than Abdellah because he never studied French literature and philosophy. He lives in Paris, but he seems like he is in the middle of a sublime Arab poem written 15 centuries ago. He knows by heart poems, he writes a diary in Arabic. He never wanted to come to France. His father obliged him to do so. He is a melancholic person and always longing for the Algerian desert where he was born, where he learns the world and where he had his first love, Saâd.

Abdellah is totally fascinated by the way Slimane expresses his Arab identity. It’s contradictions and it’s freedoms. Although he is going to leave him too, Slimane is the turning point for Abdellah –– he is in love with a man and both of them speak about this love in Arabic. It’s not a transgression. It’s more than that. It’s a revolution. They don’t need Western blessing for that love. They reinvent their Arabic identity by simply being in love with each other and by being out of any fear.

ML: Much of the book takes place in Cairo, a place certainly in the news now with the Arab Spring revolution. While most Westerners might not think of it that way, it appears in the novel to be a place very liberating for you as an Arab and, in particular, as a gay Arab. You also clearly mark it as an Arab cultural center, through film, even if the glory days are over. You also call it “a Turkish bathhouse with 20 million bathers,” which I take to mean more its intense heat, overwhelming population, and chaos. How does Cairo figure as a place of liberation for you and for your character?

AT: For me, Cairo is the most beautiful and fascinating city in the world. First I was in love with it through Egyptian movies. And, then, I became obsessive with it when I lived there for three months in 2002. It’s a chaotic city, noisy, disturbing, but constantly alive, so much alive, day and night. It’s a non-stop intensity. The way the people interact in the streets is really inspiring, the way they change their world with nothing, the way they resist is something that totally speaks to me. They are modern and so romantic. The chaos is a big part of me. Cairo is a metaphor of what I feel inside –– fear, love, desire, politics, scream, dust, sex. All the Arabs love Cairo. And, without any exaggeration, I just might be the one who loves it the most. I lived there.

This event I wrote about in “An Arab Melancholia.” It happened in 2006. I was so depressed at that time, so unhappy, my family was upset because I came out publicly some months ago. I was wandering in the streets of Cairo during many days. And, one day, near Ramses Square, I got the revelation that I do really belong to the Arab world, but it’s not a reason to diminish myself or to be all the time scared. “Ana hor!” –– I am free, in Arabic. To say that to myself in Arabic, in this incredibly noisy square, in the heart of a city where more than 20 million Arabic people live was another turning point in my life.

The other reason why I love Cairo is cinema –– this city produced the big Arabic movie stars that I still live with until today. When I was a teenager, to watch an Egyptian movie with my mother and my sisters next to me was a true definition of freedom to me. I loved and connected very much with so many of these movies.

ML: In Cairo, the character also meets Sara, the mysterious woman, a Jew who saves his life and magically disappears. She was the first Jew the character had ever met, and it dispelled all previous thoughts. Abdellah states, “All the things people told me about Jews, the things they crammed into my head I had no control over, it all evaporated, vanished in a single second.” Reading this, however, aimed at a Western audience, it made me think somehow the character is also making a statement about how little most in the West know about Muslims, as well. What is the purpose of Sara in the book?

AT: First of all, Sara is not a fictitious character. I really met her in Cairo. I changed a little bit the circumstances of this encounter but I put the truth I felt in the eyes of this woman –– the freedom to be different. Suddenly, she was more than a woman in front of me. By her presence in Cairo, she concentrates everything unfinished in me and in the Arab world. She was the element that brings another point of view and forces you to rethink everything. To start a necessary auto-critique.

There’s another character in this book that plays the same role –– it’s Karabiino, the Darfour boy who works in the hotel and who is exploited by so many people in Cairo. The Arab world change will not be complete if the different people –– gays, black, Jews, etc. –– are not also respected and protected by the law.

ML: Overall, considering all your experiences in the West and home in Morocco, what do you feel the West most misrepresents about the Middle East and homosexuality?

AT: The West knows almost nothing about Middle East and homosexuality there. Nothing about Islam as a culture, a civilization. We are all the time reduced to clichés. But, you know what? I think we should stop complaining about this misrepresentation and change these false images by ourselves. How? Simply by being who we are, to assume who we are. And to keep out of the political fear. To go to the streets again and again.

ML: Since your last book and all the news about you, how have your trips to Morocco been?

AT: All my books are present in Morocco. That’s already a big change. When I got in France the literary prize le Prix de Flore 2010 for my novel “Le Jour du Roi” [“The Day of the King”], I was in the news there. The country was somehow happy. But I am not accepted by everyone, of course. I go to Morocco several times a year. I am in Morocco while I answer this.

ML: You had a very moving piece in the New York Times about your life as a victimized gay child, the subject of ridicule and rape. What was the process of creating that essay, and, moreover, the process of getting that into the New York Times?

AT: The New York Times contacted me and asked me to write a piece for them about being homosexual in the Arab world. They didn’t specify anything else. Since my mother’s death in 2010, I am living as a gay man another struggle. I always thought that I am a strong guy inside and no one could break me, whatever happens. Meaning, in order to survive in Morocco, I had to shut down my own sensibility, to kill a part of it, to erase the hard memories of me being humiliated by so many people –– including my family –– in my neighborhood. I totally forgot about all this. And I used to say that I am a lucky guy because I feel no traumatism from that past. I was wrong of course.

When my mother died, everything changed inside of me. The little Abdellah came back, the memories I didn’t want to think about imposed themselves on me. I understood that I had no protection anymore. The last protection I could get was my mother’s. As a gay man, I was really, really alone in the world. I mean, until now (everywhere in the world), any gay man (or woman) is still a lonely man (or a woman). To be gay is a long and lonely experience.

When The New York Times contacted me, I was in the middle of all this new struggle. I took my pen and I start writing. Three weeks later, my text was published in the Sunday Review. [“A Boy to be Sacrificed,” tinyurl.com/6wsmuh7.]

ML: What is next for you?

AT: I just finished writing my next new novel, “Infideles.” It comes out in September in France. It’s about a Moroccan prostitute and her son. Marilyn Monroe is their goddess. With her, they change the way they live their religion, Islam. It’s a novel –– the pure and the impure. About faith. About the necessary need to reinvent ourselves as Muslims.

AN ARAB MELANCHOLIA | By Abdellah Taïa | Semiotext(e) Books | Translation by Frank Stock | 14.95 | 144 pages