When describing the lives of gay men and lesbians during the 1950s, when McCarthyism fanned the flames of anti-homosexual fervor, people tend to use terms like “lonely,” “repressed,” or “desolate.”

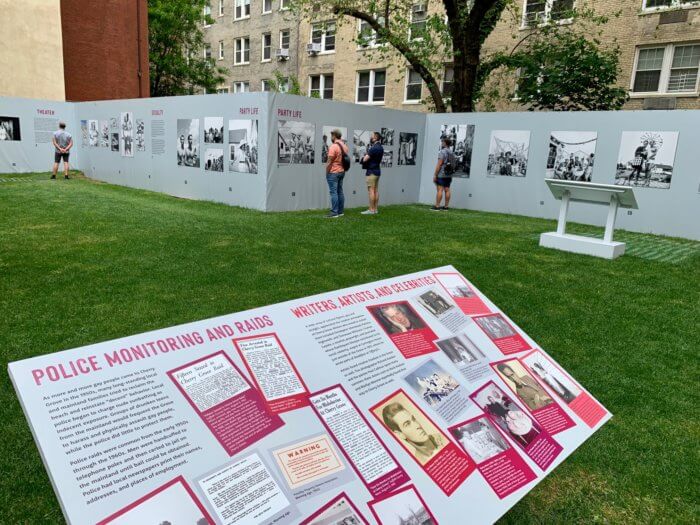

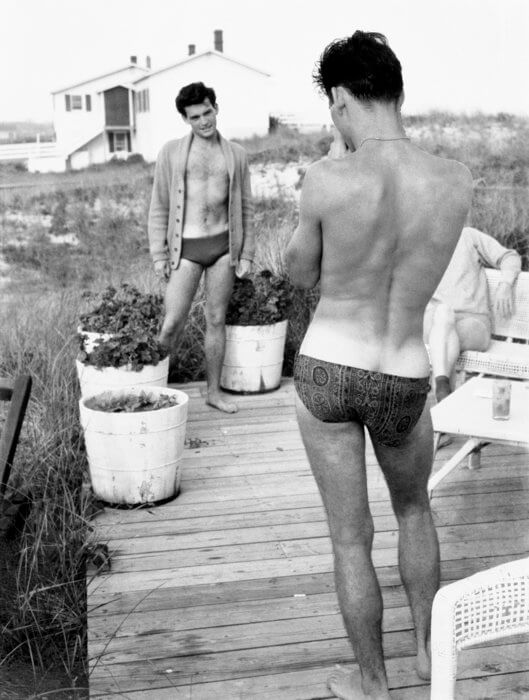

But visitors to “Safe/Haven: Gay Life in 1950s Cherry Grove,” a free outdoor exhibition on view in the rear courtyard at the New-York Historical Society, are left with a distinctly contrasting impression. The exhibit, curated by Cherry Grove Archives Collection, is filled with 70 enlarged photos portraying LGBTQ people cavorting on the beach, camping at costume parties, and hamming it up onstage at the community theater. Jaunty poses and broad smiles abound.

The exhibit also showcases postcards, flyers, newspaper clippings, and other memorabilia to help illustrate what life was like in this tiny summer retreat on a barrier island far from the bustle of New York City — and from everywhere else. The final section shows the evolution of the enclave in more recent decades.

I was so captivated that I reached out to Brian Clark, who curated the exhibit along with fellow Cherry Grove archivists Susan Kravitz and Parker Sargent. The project was coordinated at the NYHS by Rebecca Klassen, associate curator of material culture. The biggest challenge, according to Clark, was winnowing down from thousands of items in the archive.

“When we started digitizing these images, we were struck by so many pictures from house parties and theater productions,” he said. “A story emerged about how much fun these people were having during the McCarthy era when there were so many restrictions and consequences for being gay. They show joy and freedom — a stark contrast to standard depictions of homosexuals from that period.”

As Clark sees it, these repressed individuals found a vital sense of community they never had before. They were grateful to meet others like themselves, gleaning support from each other.

The earliest evidence of the Cherry Grove Archive is from the 1950s, and the collection greatly expanded in the 1970s when history buff Harold Seeley started actively assembling photos and ephemera from the shows and bars. Often items were scavenged from people’s trash, especially throughout the deadly AIDS epidemic, when families would come over, clear out the house of their deceased sons and brothers, and discard the items due to the shame and social stigma. They wanted nothing to do with these once-cherished mementoes. During that time, entire walks (the Grove’s version of streets) were wiped out.

What do they hope visitors will take away from the exhibition?

“Cherry Grove provided a safe haven in an isolated location where LGBTQ people could openly explore their identity and enjoy the experience of being open and out,” Clark said. “Which was so profound because gay people had to hide for safety. The consequences of being discovered were dire – they could lose their job and family and be shunned by their church.”

“This is one of the first places in America where the majority of residents were homosexual,” Clark explained. “I am passionate to be able to show this history. When I was young, I didn’t know any gay people. I hope that some child sees the exhibition and thinks, ‘Wow, I could be like that.’ If I had known a place like Cherry Grove existed when I was a little kid, it would have saved me a lot of time.”

He added that the community theater was uniquely gay-forward, offering ample opportunity to explore a kind of queer sensibility they could never be attempted on Broadway. Here the actors could be openly gay and present gender fluidity, camp, and full-on drag.

One of the placards explains this penchant for gender diversity, whether it be on stage or at a themed house party (with intriguing titles like “The Parasol Party” and “The Diaper Party”): “Under the guise of dressing up, many men and women were able to play with gender norms, thereby challenging society’s expectations of ‘proper’ behavior.”

An early version of “Safe/Haven” was shown at the Stonewall National Museum in Fort Lauderdale before the pandemic hit. Since then, they’ve expanded the show and swapped out certain images to make it even more resonant for today.

“We added a specific component on sexuality because we got feedback from Fort Lauderdale where a lot of guys said, ‘The beach and theater were swell, but we came there for the sex.’ We felt it was an important component that must be told.”

Despite knowing that unwitting families with young children may visit the exhibit, the NYHS never shied away from any racy content. “It was such a pleasure to work with them because they fully supported us in telling our complete story,” Clark said. “There was no moment where they tried to steer us in a direction we were unsure about. They helped us in every way.”

Not that life in the Grove was all cocktail parties, flamboyant outfits, and unbridled friskiness. The exhibit is frank about the frequent raids by police to arrest and jail men for “indecent” behavior. Gangs of teens would take boats over from the mainland just to harass and beat up the “pansies.” And not all residents in the Grove greeted gay people with open arms. Sometimes the police were called.

It includes images of newspaper clippings for the Suffolk County News with headlines like “Fifteen Seized in Cherry Grove Raid,“ and their full names were published as punishment. Often places of employment were cited as well. The curatorial team made sure to redact the last names for the exhibit, out of respect for any family members.

Clark admits it was tricky to strike a balance between the safe haven aspect and the harsh reality of persecution.

“We did struggle a bit with the dichotomy,” Clark said. “But remember, Cherry Grove was infinitely more safe than most places in America, though it did come with an element of risk.”

Another compelling element to the exhibit is the audio recordings, accessed through visitors’ cell phones, of stories from folks who were there during that period. Clark spoke with an elderly woman, a waitress at Pat’s restaurant in the Grove, who recalled that police would try to arrest as many of the gay men having sex in the dunes or woods (which came to be known as The Meat Rack) as they could, haul them into town, and handcuff them to a pole down at the harbor for all to see. She would come their rescue, bailing them out for $20.

Another welcome discovery for Clark while sifting through the material was evidence of a warm spirit of collaboration between straight and gay residents.

“It was important to show that this was a place where openly gay people and their straight friends and neighbors worked together in the theater, the fire department, the property owners’ association, and the dune fund,” Clark noted. “That was certainly not the norm in America at that time. People got to know each other and, as silly as this sounds, straight people discovered that, well, homosexuals are people too.”

I asked Clark if he feels that a strong sense of community still exists today.

“Absolutely,” Clark responded. “We had no idea when we bought a house there in 2006 that there was such an amazing community. There are have so many wonderful people who are passionate about their town. It still has a majority of gays, but we love our straight allies. It’s like small town USA, but it’s gay.”

One of the additions since the original run was addressing lessons learned from the Black Lives Matter movement. As a committee, they felt deeply passionate about the cause.

“We looked at the images and wanted to acknowledge that in the 1950s America was still segregated and people of color were discriminated against,” Clark said. “We can’t change history, but we’d like to note it. While it was a safe haven for white people, we are not sure people of color felt comfortable there. We tried to touch on that topic to show that things have improved and there are more people of color now. We felt it was important to include that.”

SAFE/HAVEN: GAY LIFE IN 1950s CHERRY GROVE | New-York Historical Society rear courtyard | 170 Central Park West (entrance on 76th St) | Friday 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.; Sat. & Sun. 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. through October 11, 2021 | Free timed entry tickets booked in advance at NYHistory.org