David LaChapelle chronicles the emergence in South Central of America’s next dance craze

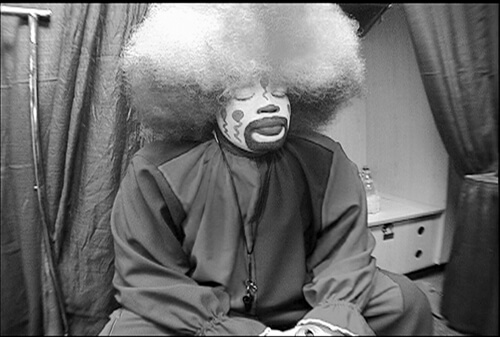

In “Rize,” the documentary debut of the noted photographer David LaChapelle, the performer “Tommy the Clown” Johnson is seen in his trademark costume that he began wearing in 1992 in response to the riots that destroyed South Central, Los Angeles. In a scene from the film, performers line up on a Los Angeles street for a dance competition.

David LaChapelle is best known as a celebrity photographer and music video director. His documentary debut, “Rize,” is an electrifying look at new dance forms emerging among African-American youth in South Central Los Angeles. The film sustains a rhythm that clearly aims to frame a new story of hope emanating from the neighborhood remembered as a riot zone following the 1992 acquittal of four white police officers caught on tape beating Rodney King. The riots lasted for 72 hours and resulted in the deaths of 54 people and the destruction of scores of homes and businesses.

“Rize” offers an intimate look at an emerging underground dance movement—“clowning” and “krumping”—that is the descendant of native African dance movements and emblematic of the African-American heritage of lending innovation to American music, largely in response to tragedy.

Thomas “Tommy the Clown” Johnson is a former thug who dons a clown costume in the early 1990s to consciously parody South Central’s demise following the fires and violence ignited by the cop defendants’ not-guilty verdicts. With his bold, self-expressive, style Johnson found many followers in South Central.

Over a decade later, LaChapelle films the various permutations of the movement that Johnson inspired. The camera follows kids on the streets, in school and at home. In various interviews, South Central residents speak of Johnson as a local savior. After years of backing up the clown, some of his dancers are moving out on their own, forming their own troupes. Now called krumpers, they still wear make-up, but of a different, decidedly less comic sort, evocative of superhero figures combating the materialism that they regard as corrupting the once-revolutionary hip-hop culture.

One dancer explains that you can krump to escape the tensions of daily life, like coming up short on paying bills. She then feverishly twists, wobbles, bounces and shakes off the anxiety of months of late rent and an overdue cell phone bill.

Much of “Rize” is a lead-up to a major dance competition planned for the Los Angeles Forum. Larry, Dragon, Baby Tight Eyez, Swoop, Daisy, La Nina, Lil Tommy, Lil C, Tight Eyez, Ms. Prissy, El Nino and Big X are some of the dancers who have endured difficult childhoods in Los Angeles’ inner city.

The bout is memorable. When clowner La Nina and krumper Ms. Prissy face off, the crowd roars. One dancer sits in a chair, facing her opponent, and submits to the physical taunting and dance-spurred humiliation inflicted by her rival—much like the vocal square-offs of Eminem’s“8 Mile.”

Viewers are told at the start that “the images in this film have not been sped up in anyway.” Many of the dance moves—the springing back and forth, the arching of backs, the gyrating hips and the flailing arms—resemble actual fighting. The style is a mixture of spiritual African dancing, chaotic mosh-pit shoving and martial arts moves syncopated to a hip-hop beat.

Aggressive pushing is part of the movement and nothing personal, say the participants, though it is hard to believe that fierce rivalries don’t emerge from these dance-offs. Johnson himself confronts the harsh and unsettling reality of having his house torn apart after a major competition between the clowns and krumpers.

LaChapelle mixes footage of the clowners and krumpers with those of traditional African tribal dancers. The juxtaposition is intended to make the point that the make-up and dance styles are authentic African rituals resurfacing on the streets of contemporary Los Angeles.

Like many cultural fads and artistic innovations introduced by African Americans, “mainstream” America—meaning white suburban youth—as well as Latinos and Asians, are also picking up the style.

Some of the dance moves are overtly sexual, even though, as one krumper explains, much of the dancing involves moving alone and avoiding contact with other dancers. It is clear that the artistry in clowning and krumping is an emerging art form that will likely dominate pop music videos once the movement crosses the racial divide. There’s passion and soul here that many current videos lack.

The dancers in “Rize” possess a natural, magnificent talent. The moment these youth grace the stage, battle-ready, they are consumed by the practice of their art. No longer kids that practice dance moves in secluded venues after school, they become true stars, warriors armed with skills that students at highly regarded dance schools are lucky to come away with.

The musical score by Amy Marie Beauchamp and Jose Cancella— featuring music by Elton John, Lauryn Hill, Christina Aguilera and Flii Style—evokes the urgency felt by many dancers that a superior performance could bring about lifetime opportunities. Indeed, Ms. Prissy has earned spots in music videos for the rapper Ludacris and is currently on tour with The Game, a protégé of rap legend Dr. Dre. Engaging, poignant, genuinely entertaining and often comedic, “Rize” offers the heartfelt message that creative self-expression is an effective antidote to life’s travails.

For some South Central youth, this new dance innovation may provide the chance to finally break free from the racial and economic bonds that have locked them down for far too long.

gaycitynews.com