Kansas appeals court says Romeo and Juliet Law does not protect gay sex

Adopting an extremely narrow view of the scope of two key U.S. Supreme Court pro-gay rulings, including last summer’s sodomy decision, a three-judge panel of the Kansas Court of Appeals voted 2-1 on January 30 to reject a challenge to 17-year prison sentence imposed on Matthew R. Limon, who just after turning 18 engaged in consensual oral sex with another youth who was almost 15.

Both Limon and the other youth were residents of an institution for developmentally disabled youth.

Under Kansas criminal statutes, “sodomy” between an adult over 18 and a minor is a serious felony, exposing the perpetrator to a lengthy prison term. However, a separate statute––the so-called “Romeo and Juliet Law”––enables prosecutors to charge young adults no more than four years older than their opposite sex partners under a less severe statute that carries a sentence that in Limon’s case would have amounted to 13 to 15 months in prison.

When he was prosecuted under the more punitive statute, Limon’s attorney argued that the two youth were close in age and that the sex was consensual (and that Limon stopped when asked to do so by his partner) so the Romeo and Juliet Law should apply. The attorney asserted that the failure of that statute to cover Limon’s situation was a violation of his right to equal protection under the law guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

The Kansas courts rejected that argument, and Limon was sentenced to 17 years and two months in prison.

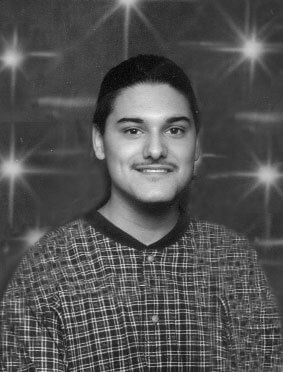

The young man, who will turn 22 this month, has been in jail since the summer of 2000. Now incarcerated at the Ellsworth Correctional Facility, Limon is able to practice his love of music on a piano that his parents, Mike and Debby, were able to have placed in the prison. Mike Limon’s sister, Blanche Hayden, told Gay City News that Matthew’s parents do not wish to speak to the press or be in the public spotlight, but are loving and supportive of their son.

The Lesbian and Gay Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), representing Limon on appeal, urged the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn this result on equal protection grounds. The day after the sodomy ruling came down last year, the high court sent the case back to the Kansas courts for “reconsideration in light of Lawrence v. Texas.”

In Lawrence, the court struck down the Texas Homosexual Conduct Law, finding that it abridged the liberty of a same-sex male couple prosecuted for engaging in a private act of sodomy. In response to Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion which employed broadly worded liberty rhetoric rather than engaging in a traditional technical due process analysis, Justice Antonin Scalia dissented that the Court had “not” declared gay sex a “fundamental right,” but instead struck down the Texas law because it could find no rational basis for it.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor concurred with the majority in an opinion based on an equal protection analysis, invoking the court’s 1996 Romer v. Evans ruling that struck down Colorado’s anti-gay Amendment 2.

Returning to the Kansas courts, the ACLU argued that Limon’s sentence must be set aside in light of Lawrence, but a majority of the panel was not convinced. In separate opinions, Judges Richard Green and Tom Malone each asserted that Lawrence did not control this case, pointing out that Kennedy had specifically observed that Lawrence did not involve minors. Neither judge was willing to find that adults have a constitutionally protected right to engage in gay sex with minors, even when the “adult” and the “minor” are close in age.

Borrowing Scalia’s argument that Lawrence was a “rational basis” case, and taking a similar view of Romer v. Evans, the majority on the Kansas panel asked whether the state has a rational basis to impose a lengthier sentence on an adult for sodomy with a minor of the same sex rather than the opposite sex.

Green found convincing the state’s list of reasons, including some that one might find very questionable in light of the Supreme Court majority’s rhetoric in Lawrence, especially those reasons grounded in moral judgments about homosexuality, such as protecting “traditional morality.” Green picked up his second panel vote from Malone, who accepted the state’s assertion that homosexual sex presents greater health risks than heterosexual sex, particularly between males.

For dissenting Judge G. Joseph Pierron, this was a step too far. Pierron found the justifications offered by the state either irrational or ruled out by Lawrence, criticizing some of the state’s arguments as “incomprehensible.”

“There is a facial connection between penalizing consensual criminal sexual relations with a minor and concerns about venereal diseases,” Pierron wrote, addressing the issue that won Malone over. “However, there is no reasonable support presented for much greater criminal punishments for any homosexual acts than for any heterosexual acts. One must first note the obvious fact that there is no difference in the penalties imposed under the Kansas law based on whether the defendant actually does or does not have a venereal disease. This is a very important omission if the law was truly concerned about venereal disease.”

Pierron was particularly critical of the majority’s resort to rhetoric about morality, and concluded: “Carved in stone above the pillars in front of the United States Supreme Court building are the words ‘Equal Justice Under Law.’ In bronze letters on the north interior wall of the Kansas Judicial Center we read ‘Within These Walls The Balance of Justice Weighs Equal,”… Persons in power and authority have historically been tempted to discriminate against people they do not like or understand… This blatantly discriminatory sentencing provision does not live up to American standards of equal justice.”

Tamara Lange, the ACLU attorney who argued Limon’s appeal, termed the rational bases cited by the state for their argument “absurd,” but said that even if Kansas were to offer legitimate rational grounds, the precedents set by Lawrence and Romer would require a higher level of scrutiny than mere rationality.

Though Lange has not yet consulted with Paige Nichols, ACLU’s local co-counsel, she assumes that the case will be appealed to the Kansas Supreme Court.

In a story written by Nadia Flaum in The Pitch, a Kansas weekly, Phill Kline, the state’s attorney general, argued that he has defended Limon’s harsh sentence because the youth was subject to two cases of “juvenile adjudication” at the age of 14 on the charge of sodomy, both counts on the same day. The records in that case have been sealed and Lange said the appeals court proceedings offered no public insight into the nature of the sodomy, including whether it was consensual.

Nevertheless, Kline told The Pitch, “[Limon] is a repeat offender who commits sex offenses against children.”

Lange responded by calling Kline’s claim a “smoke screen,” explaining, “The state attorney general is trying to make it out that this is a case about a sex offender, when in fact it is a question of equal protection.”

She said that a young adult found guilty of sodomy with a minor only several years younger with a history of two previous juvenile adjudications would have gone to jail for 13 to 15 months. If only one such adjudication had taken place, the penalty would have been probation, Lange said.