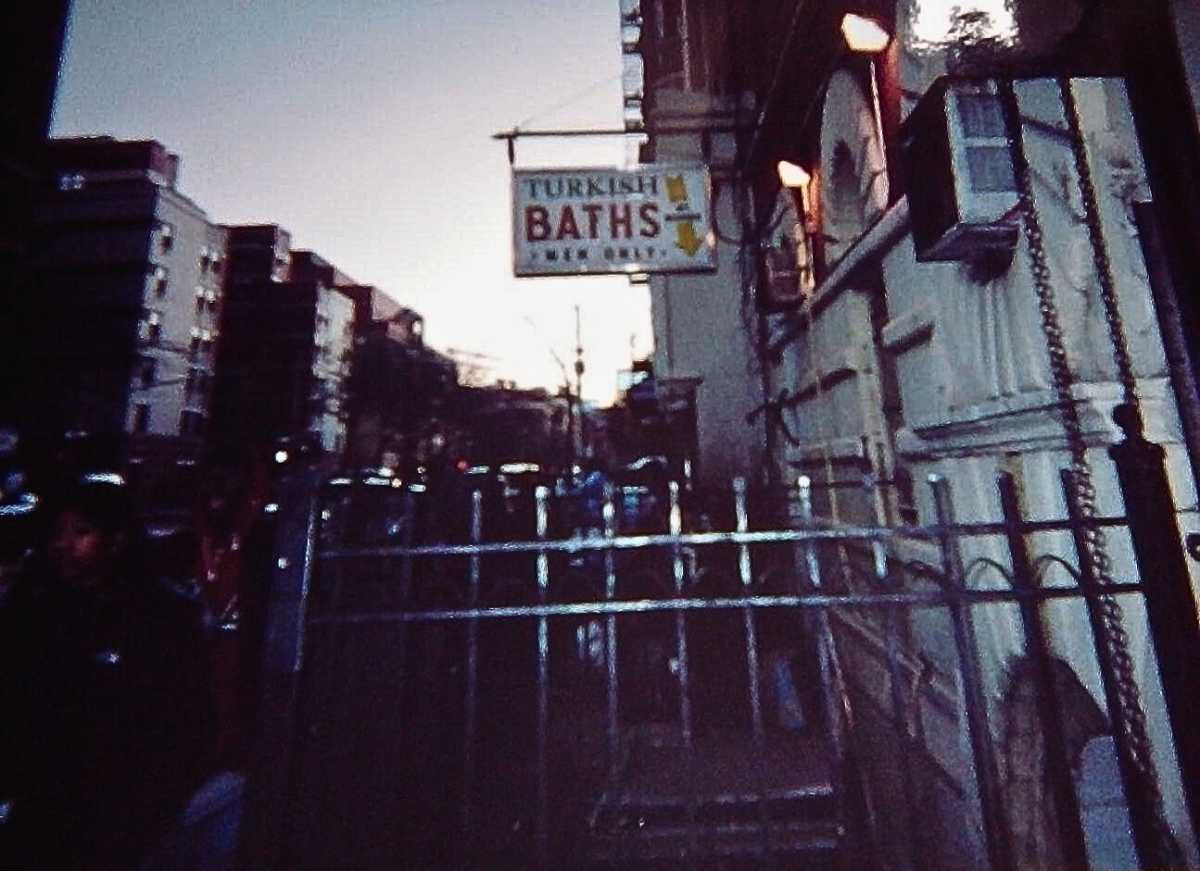

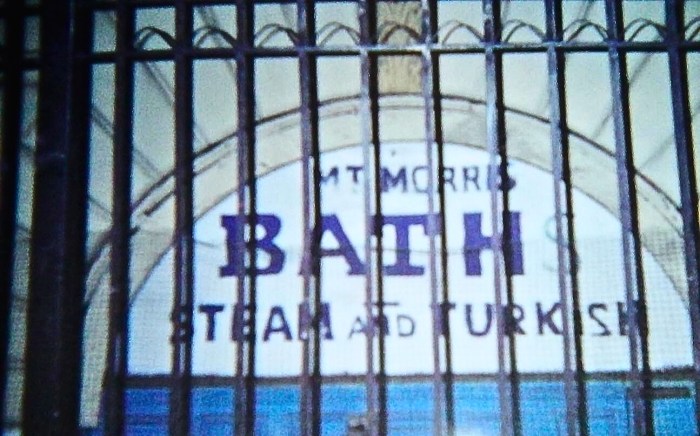

Friday and Saturday nights, regardless of the weather, were the busiest at Harlem’s Mount Morris Baths, the oldest Turkish bathhouse in New York until it closed in 2003.

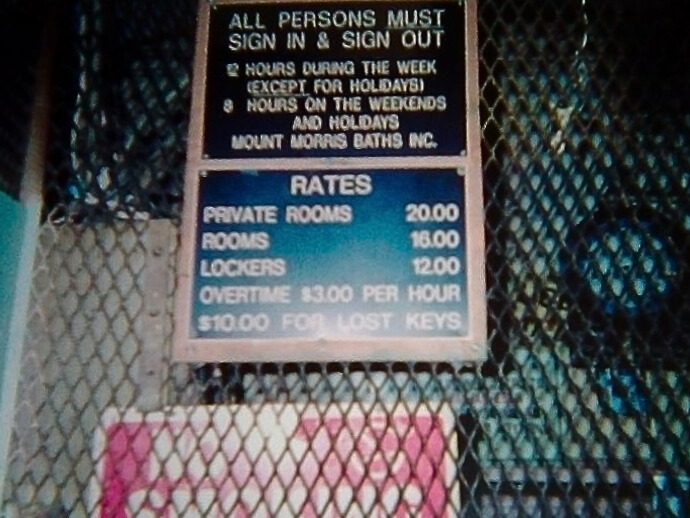

The men, mostly Black, sat on a long wooden bench or stood elbow to elbow, shoulder to shoulder, in a tiny vestibule, near the cashier’s window, waiting for a room or a locker to become available. Sometimes, they waited two or three hours. Being in such close proximity to each other often caused tempers to flare, especially if someone was thought to have jumped the line. On rare occasions, angry words escalated into fistfights. But, the customers, for the most part, maintained their cool. Once inside the bathhouse, which was at 1944 Madison Ave. on the southwest corner of 125th St., they had eight hours (12 on weekdays) to explore the rooms, corridors, and other areas of an establishment that had been in operation, it has been said, since 1893.

That was the year when a group of Jewish doctors built it as a health spa for their patients. Sometime in the 1940s it became a gay bathhouse, though the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project notes that it may have drawn gay clientele as early as the 1920s. In his book, “The Other Side of Silence,” the historian John Loughery wrote that “it catered to Black men who were often denied admission to bathhouses in midtown Manhattan.”

I worked at Mount Morris Baths for two and a half years — first as a towel attendant, then as a cashier — so whenever I pass what was once the bathhouse, the customers, the co-workers, and the experiences, good and bad, instantly come to mind.

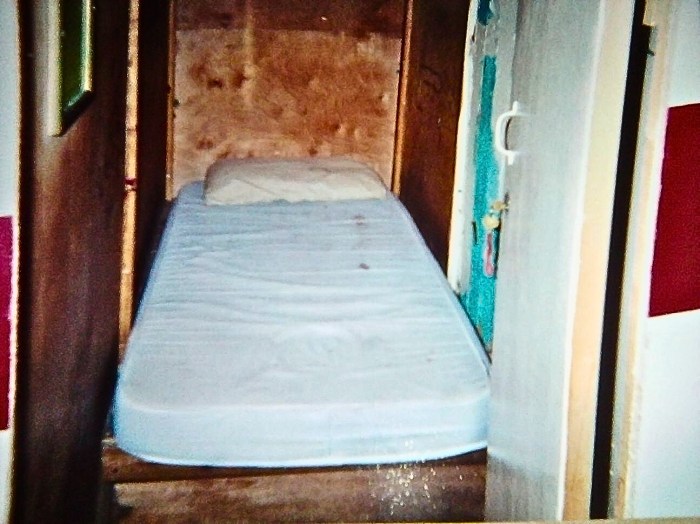

Upon entering the TV lounge/dormitory, it became apparent that this place would never appear on the front cover of Architecture Digest or Better Homes & Gardens. It looked and smelled every bit of its hundred-plus years. The Fab Five of the reality show “Queer Eye” would have had a field day doing an extreme makeover. Oddly, many customers preferred its antiquity and shabbiness. Mount Morris was sort of like the old man down the street whose shoes are turned over, pants baggy and soiled, face wrinkled, body decrepit, but is still regarded with kindness.

Even though it had seen better days, for many of its customers, it was their second home. For some, it was home, offering a place to bunk down, take a shower, and have a free morning cup of coffee (with donuts).

One customer told me, “If these walls could talk.” Indeed. The tales would fill several volumes about several celebrities (past and present) and non-celebrities who were spotted getting a rubdown or sitting in the hot room or going in or coming out of someone’s room.

Of the two jobs I held there, the cashier one was undoubtedly the most dangerous and nerve-wracking, because the cashier’s booth (often referred to as the office) offered no protection from criminals. Subway booth clerks had more protection than we did. Only plywood separated us from the customers. Since we handled money and kept customers’ wallets and other valuables in various index card file drawers, there was no protection from a bullet. There was a closed-circuit monitor that let us see who was coming down the outside stairs and what was happening in the two TV lounges. But there was no panic button to press or phone system in the office to use in case of trouble. At the time I didn’t own a mobile phone. The only phone available was a few feet away, outside the office, in a coin-operated phone booth. Not very convenient if I needed to summon help.

The nerve-wracking part of the job included being on the lookout for phony bills a customer would knowingly or unknowingly hand us, checking people in and out, notifying patrons to renew their time when they stayed past eight hours (or, again, 12 hours on the weekend), refunding money lost in of one the vending machines, distributing condoms and lube, etc. At the end of the shift, I had to tally all the money in the cash register and deposit it in a manila envelope in a drop box behind me for later pickup by Walter, the owner. As you can see, the job required me to be on my toes at all times.

Despite these headaches and the rundown condition of the bathhouse, I still miss Mount Morris and its interesting, sometimes bizarre cast of characters fit for a TV sit-com.