Director Chris McKim’s outstanding documentary “Wojnarowicz: Fuck You Faggot Fucker,” about David Wojnarowicz, uses the late gay political activist and multimedia artist’s journals, cassettes, photographs, paintings, and super-8 films to recount his life and work. The film is a remarkable testament to the downtown artist as an angry young man.

Wojnarowicz grew up in an abusive home and spent time on the streets as a hustler before he developed a career in the 1980s art world alongside contemporary graffiti artists, including Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Yet he had justifiable contempt for both the gallery system that served rich, white culture, as well as the politicians and conservatives who condoned homophobia in their efforts to stop federal funding for controversial artists like himself. He was the subject of various lawsuits regarding politics, funding, and art, and even won one against Donald Wildmon, who used the artist’s work inappropriately to send messages of hate.

Diagnosed with AIDS, Wojnarowicz pointedly observed, “I contracted a diseased society as well.” He became a member of ACT UP, and penned an incendiary essay, “Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell,” as part of the catalog for the 1989 exhibition “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing” as a response to the AIDS crisis. (Alas, the documentary does not feature much of its subject’s writing. It briefly mentions his efforts to get “Sounds in the Distance” published, but nothing about his memoir, “Close to the Knives.”)

Wojnarowicz’s work was extremely influential, and as an early clip in the documentary shows, he talked about the inability to separate art from politics. His work was never polite and always confrontational. McKim features a significant portion of his drawing and painting in the film, emphasizing the point that his art was a way for him to process his life. (A film clip of Wojnarowicz with a rabbit stems from a shocking incident from his childhood when his father fed the family’s pet rabbit to David and his siblings).

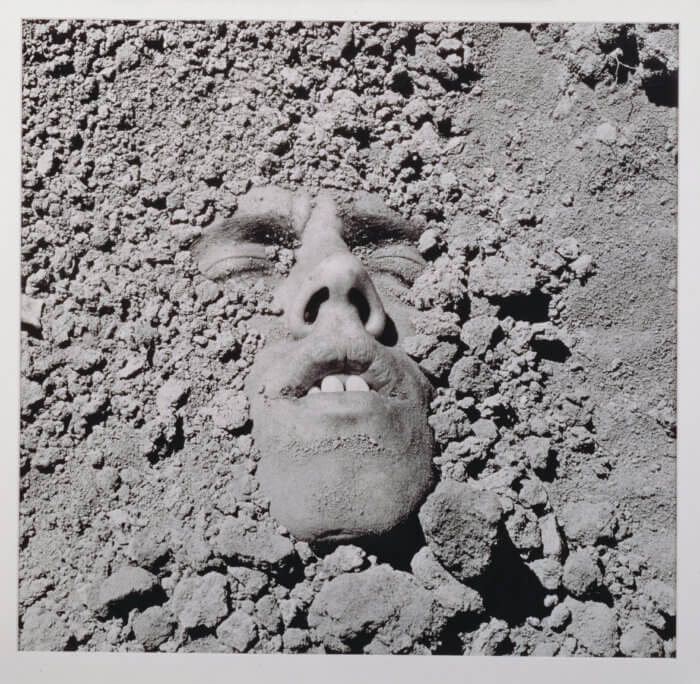

His early work featured images of Rimbaud and Genet, two of his outsider idols. He also created content with Peter Hujar, who was Wojnarowicz’s greatest influence, friend, father figure, and, briefly, his lover. Hujar told him not to compromise or adapt to other people’s tastes — and that was advice he took to heart. Wojnarowicz’s photographs of the Hujar’s head, hands, and feet from his deathbed are among his most poignant images.

McKim’s documentary traces its subject’s career, from performing songs about the underclass with the band “3 Teens Kill 4” to his “action installation” with Julie Hair — involving cow bones, blood, and stencils in Leo Castelli’s gallery — until his breakout in the East Village art scene in 1982. He also established an illegal, surreptitious artists’ space in the Hudson piers, which was quite successful until the police shut it down.

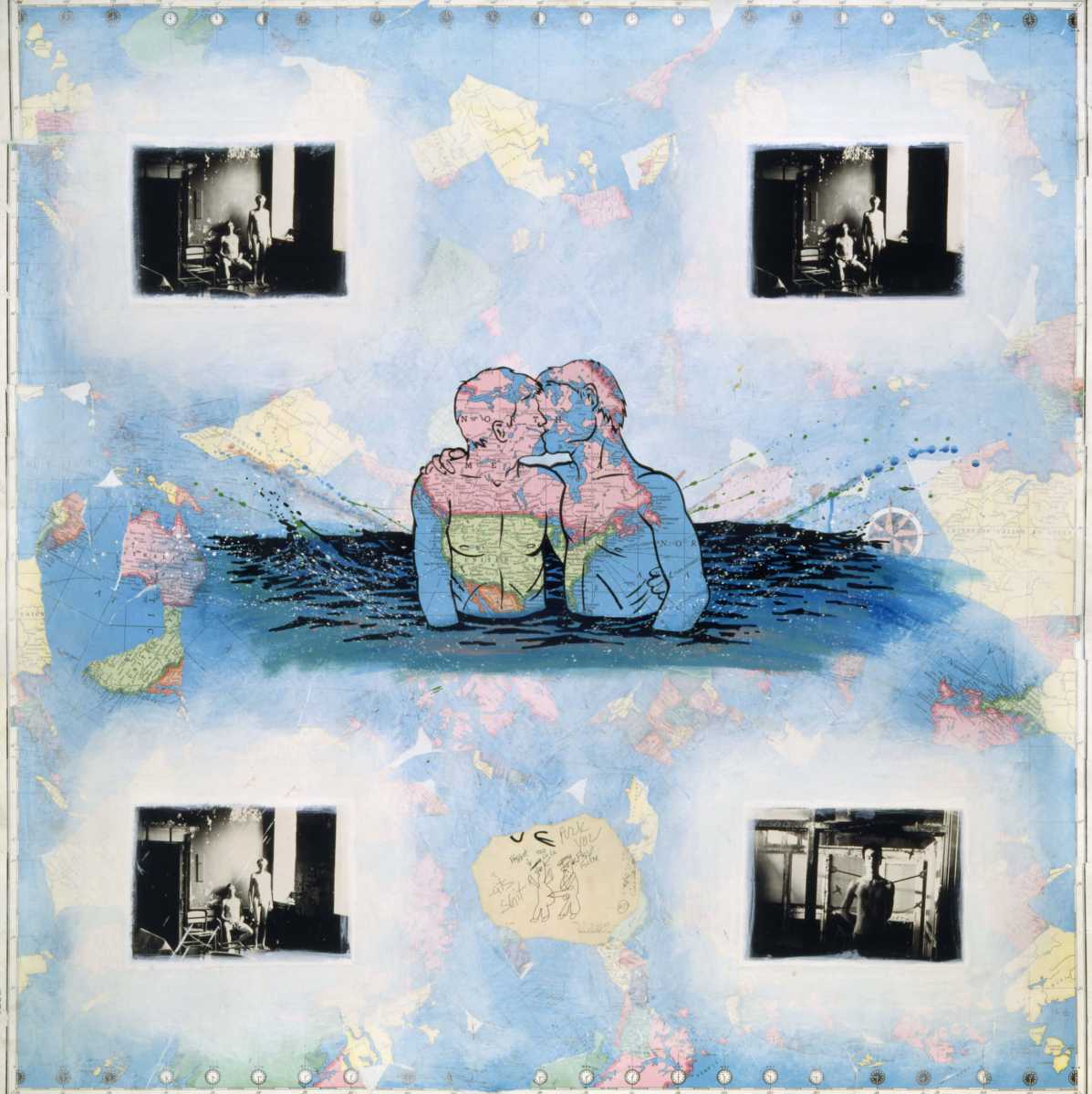

When Wojnarowicz’s work was shown at the Gracie Mansion gallery, Grace Glueck, a New York Times arts reporter, wrote about it and the emerging queer sensibility. Suddenly, Wojnarowicz started getting noticed. And his paintings, “Fuck You Faggot Fucker” and “Prison Rape,” expressed, in no uncertain terms, what being queer in America was like.

The film celebrates Wojnarowicz’s raw, uncompromising politics and consciousness and McKim emphasizes the artist’s claim that his work was not a product. When two of his paintings were selected for the 1985 Whitney Biennial, Wojnarowicz practically shrugged; he did not look for acceptance in the larger art world. Viewers will likely snicker when Wojnarowicz is commissioned to make an installation for Robert and Adriana Mnuchin, which he filled with the dirtiest trash he could find — and bugs.

McKim does focus on Wojnarowicz’s personal life. There are exchanges he had with his sister Pat and his brother Steve, the latter of whom has a very tense conversation with him when Wojnarowicz is dying of AIDS. There is a discussion of his using heroin — and stopping when Hujar insisted. And there are also some very revealing interviews with Tom Rauffenbart, who was the artist’s boyfriend. Rauffenbart wistfully describes Wojnarowicz prioritizing Peter first, his art second, and his lover third, acknowledging, grudgingly, that it made sense.

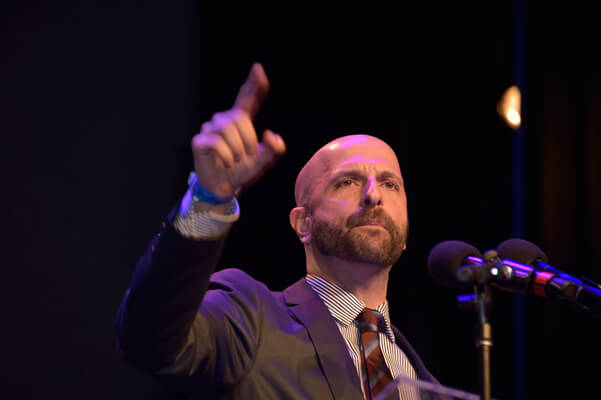

“Wojnarowicz” does not coddle its subject or viewers. There are graphic images that disturb or may offend, such as the iconic image of the artist with his mouth sewn shut, or depictions of graphic sexuality, but McKim is not looking to shock or exploit. He is assembling the work to show the rage Wojnarowicz felt. Watching clips from the ACT UP demonstrations he attended are galvanizing. At the St. Patrick’s Cathedral protest, the artist wore a jacket that read, “If I die of AIDS — forget burial — just drop my body on the steps of the FDA.” And at Wojnarowicz’s political funeral, men carried a banner that read, “Wojnarowicz died of AIDS due to Government Neglect.”

One can, of course, only wonder what the artist would have created had he lived. Retrospectives of Wojnarowicz’s work at Illinois State University in 1990, while he was alive, and a more recent one at the Whitney in 2018, show the lasting impact of his work. They also magnify a cogent point made in the film about “expressing ideas that may change yours.” Such is the power of the artist, and the takeaway from McKim’s excellent “Wojnarowicz.”