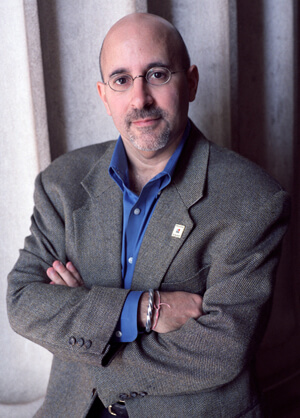

Freedom to Marry’s Evan Wolfson is among the critics of the current religious exemption language in the proposed Employment Non-Discrimination Act. | FREEDOM TO MARRY

BY DUNCAN OSBORNE | When the federal Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) was proposed last year, leading LGBT legal groups said the religious exemption in that legislation was too broad and would allow discrimination by too many employers.

Proponents of ENDA, which bans employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, were silent and refused to engage in that debate as the legislation won a 64 to 32 vote in the US Senate, then went on to likely death in the House.

This year, a bill that passed the Arizona Legislature granting protection from lawsuits for people and businesses that deny services to others based on their religious beliefs prompted furious opposition across America and was quickly vetoed by Jan Brewer, Arizona’s Republican governor.

The groups that opposed ENDA’s religious exemption are now pointing to the furor over the Arizona law and saying that Americans do not support such broad religious exemptions to anti-discrimination laws and ENDA must be changed.

LGBT legal advocates warn of dangers in broad language, but key ENDA backers remain mum

“While the scope of the religious exemption language in the current draft of ENDA is nowhere near as all-devouring as the bill we just defeated in Arizona, it still is far broader than the comparable language in the Civil Rights Act and most state laws, and must be fixed,” Evan Wolfson, the president of Freedom to Marry, a gay civil rights group, wrote in an email. “There should be no license to discriminate when it comes to employment, other than in truly religious offices on the part of truly religious entities. And discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity should get no greater leeway than other forms of discrimination.”

The Arizona bill changed the definition of a “person” in an existing religious exemption law to “any individual, association, partnership, corporation, church, religious assembly or institution, estate, trust, foundation or other legal entity.”

If sued, a person or one of these entities could assert in a defense that their religious beliefs were burdened by having to, for example, serve a same-sex couple. Proponents of the Arizona law said it was intended to protect religious liberty, but opponents said it targeted LGBT Americans.

While ENDA’s language does not go as far as the Arizona law, those groups concerned about it said it goes beyond the religious exemption in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and allows religiously affiliated hospitals, schools, and other entities to discriminate.

“We’ve been very critical of the scope of ENDA’s religious exemption,” said Ian Thompson, a legislative representative in the ACLU’s Washington, DC lobbying office. “We’ve repeatedly pointed out that this exemption would be unprecedented in federal law.”

ENDA’s religious exemption was also opposed by Lambda Legal, the National Center for Lesbian Rights, and the Transgender Law Center.

A number of state legislatures are weighing laws that are similar to Arizona’s, though several appear to have abandoned the bills in light of the ferocious response to Arizona’s law.

“If there’s one thing that the uproar over [the Arizona law] tells us, it’s that the American public does not see discrimination against LGBT people as acceptable,” Thompson said. “I think it’s time that ENDA’s religious exemption reflects that reality… I do not think that the American public favors blank checks to discriminate against LGBT people.”

The Human Rights Campaign (HRC), the country’s leading gay rights lobby, supported ENDA and called for a veto of the Arizona legislation. HRC saw a world of difference between the Arizona law and ENDA.

“Bills like Arizona’s go far beyond the exemption in ENDA and many similar state nondiscrimination laws to provide any individual the ability to undermine nondiscrimination protections and refuse employment and services to anyone, including an LGBT person or family, based on his or her private religious beliefs,” HRC said in a statement. “This would make a law like ENDA, with or without an exemption for religious groups, vulnerable to any person who expresses a religious objection to being bound by it. That is an incredibly dangerous precedent to set.”

Tico Almeida, who heads Freedom to Work, also an LGBT civil rights group, authored ENDA’s religious exemption while a congressional staffer. He has defended the exemption as no different from the language in the Civil Rights Act, though he conceded at a forum last year that it would allow discrimination by some religiously affiliated non-profits. He did not respond to an email seeking comment.