BY DOUG IRELAND | Florida is once again a key state in deciding the presidential election and also among the states where conservatives have recently put in place racist laws designed to suppress the black vote, so it is crucial to understand how deeply entrenched 60 years ago the resistance to racial integration was in the Sunshine State. And, in a timely new book from the University Press of Florida, “Communists and Perverts Under the Palms: The Johns Committee in Florida, 1956-1965,” Stacy Braukman, a young, independent queer scholar, has done a masterful job of dissecting how the weapons arrayed to preserve segregation in that era were turned on Florida’s emerging, though still largely closeted, gay community in an anti-homosexual witchhunt that lasted more than a decade.

BY DOUG IRELAND | Florida is once again a key state in deciding the presidential election and also among the states where conservatives have recently put in place racist laws designed to suppress the black vote, so it is crucial to understand how deeply entrenched 60 years ago the resistance to racial integration was in the Sunshine State. And, in a timely new book from the University Press of Florida, “Communists and Perverts Under the Palms: The Johns Committee in Florida, 1956-1965,” Stacy Braukman, a young, independent queer scholar, has done a masterful job of dissecting how the weapons arrayed to preserve segregation in that era were turned on Florida’s emerging, though still largely closeted, gay community in an anti-homosexual witchhunt that lasted more than a decade.

The federal government’s purge of homosexuals, which began under President Harry Truman in 1947 and gained startling momentum as Senator Joe McCarthy came to dominate national politics, is well-documented and widely known among the gay reading public. At the height of the nation’s domestic Cold War, paranoia about a non-existent internal “Red menace” lumped sexual deviants and Communists together as a subversive threat to the nation. (David K. Johnson’s seminal 2006 history “The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government,” available in paperback from the University of Chicago Press, documents how the era’s political demagoguery “sparked a moral panic within mainstream American culture.”)

Less well-known is the story of how a skein of “little McCarthy committees” were established in numerous states to root out “subversives” — and especially of how, in the states of the old Confederacy, these institutions became a front-line weapon against the nascent civil rights movement for blacks.

Stacy Braukman’s new book demonstrates how the legacy of racism and homophobia in Florida state government 60 years ago remains timely today. | UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA

Braukman’s book shows us how “race and sexuality” are “central rather than peripheral to our understanding of domestic anti-Communism.” In the South, political subversion and sexual deviance were seen as dangerously related to each other, a notion that “converged with whites’ ideas about black sexuality to create a discourse on deviance through which they articulated their opposition to integration as well as to communism, liberalism, or progressivism in virtually any form.”

The Florida Legislative Investigative Committee (FLIC) was set up in 1956 as the state’s response to the US Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education ordering integration of the schools. FLIC was known as the Johns Committee after its founder, Charley Johns, a militant segregationist and the State Senate president who had narrowly lost his gubernatorial reelection campaign two years earlier.

Modeled explicitly on both the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that made Richard Nixon a national figure and the equally nefarious anti-integration Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, the Johns Committee’s first target was the NAACP, which had led a bus boycott against segregation in public transportation in Tallahassee.

By 1958, however, the Johns Committee had failed to prove that the NAACP was dominated by Communists and had also been denied its membership lists in a series of court victories by the civil rights group. As a result, Johns next turned FLIC’s attention to a full-scale investigation of homosexuality at the state’s flagship school, the University of Florida at Gainesville. As Braukman writes, Johns calculated that “the investigation of gay professors at the University of Florida [would] save face and redeem his committee’s name at a time when the NAACP investigations were flagging.”

Working closely with both local and university police, the committee’s chief investigator, R.J. Strickland, set up entrapment stings in public bathrooms not only at the university but as well at the county courthouse in Gainesville, where the toilets had for decades been known as a homosexual cruising site. These stings apprehended not just students and faculty from the university, but also truckers, teachers, traveling salesmen, local businessmen, and day laborers.

“Virtually none was openly gay or even comfortable in acknowledging his homosexual behavior,” Braukman writes.

Finding that it was easier to expose queers than to find Communists in the NAACP, Johns quickly expanded his anti-homosexual purge to other universities, to public schools, and to state agencies. In 1961 Johns got an ally in the newly elected segregationist governor, C. Farris Bryant, who proclaimed, “Recent crime investigations in our state clearly indicate that homosexual activity is widespread. The true impact of this menace to our society is not fully felt until we realize that our youngsters, the youth of our state, are prime targets for homosexuals who continually seek to proselyte [sic].”

The Johns Committee subsequently cosponsored a series of educational conferences around the state in cooperation with Bryant’s Florida Children’s Commission, designed to root out “indecency and homosexuality” in Florida, particularly in the schools — prefiguring by more than a decade and a half the “Save the Children” crusade of another Bryant, Anita, who led the successful 1977 effort to repeal through a referendum a Dade County ordinance banning discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation.

Through these public conferences, citizens across Florida were asked to join in unmasking suspected homosexuals, and FLIC was soon inundated with complaints and accusations naming suspected queers in university faculties and among the teachers in the state’s public schools.

These putative queers and others entrapped by FLIC’s stings were hauled before secret hearings of the Johns Committee and, under threat of public exposure, forced to collude in the obscene ritual of “naming names” of others with whom they’d had homosexual encounters, just as the HUAC investigators had done with suspected Communists and their sympathizers.

The Johns Committee widened its dragnet to include pornography, enlisting local police chiefs to conduct raids on homes that netted private collections. FLIC also targeted teenage prostitutes, who under threat of jail terms were browbeaten into giving the names of their clients.

By the early ‘60s, the triumph of Fidel Castro and his adoption of a Communist ideology in Cuba heightened Cold War anxieties in Florida, and against that background, Johns Committee efforts reaped huge publicity spreading “the ideas that homosexuals preyed upon and recruited children and that gay teachers had to be exposed and removed. Perhaps most of all, they stirred up fear among parents and the public that they were not safe — that, in addition to agitating Negroes and treacherous Communists ninety miles to the south, now Floridians had to fear pornography-wielding deviates.”

Scores of gay teachers from all over the state identified in the committee’s files were targeted and fired.

Strickland, the committee’s chief investigator, appearing at a meeting of the anti-integration Southern Association of Intelligence Agents, said, “Homosexuality is playing a big part in our present racial problems and in the promotion of Communism.”

FLIC’s decline began when Strickland overreached, paying a female informant to lure an Orlando Sentinel reporter to a hotel room where she forced his head down between her legs and gave the signal for the FLIC spies to burst in and “catch” the journalist in an “unnatural act” illegal under the state’s sodomy statute. Strickland had to resign his post with the Johns Committee.

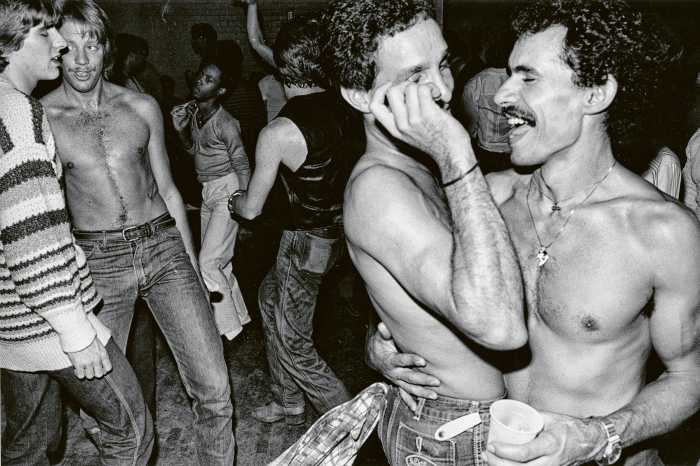

In 1964, the committee issued a lurid report, “Homosexuality and Citizenship in Florida,” which it sold for 25 cents a copy. The report was illustrated with a photo of a teenage boy clad in a g-string and bound with ropes “taken from a homosexual’s collection” and another showing a man being fellated through a glory hole in a public toilet. The cover showed two men stripped naked to the waist and engaged in a passionate lip-lock. The pamphlet was deemed so prurient that the Dade County state’s attorney called it “obscene” and threatened legal action to halt its sale.

Braukman does a brilliant job of showing how anti-Communism “allowed Southern conservatives to construct other enemies” characterized by the same baleful attributes as the supposed Communists targeted in the Red Scare. They were successful in casting “homosexuals as secret infiltrators, polluters, and corrupters, and integrationists as secret race mixers and statists.”

She also shows how the public discourse established by Johns Committee activities was the linear predecessor of the “culture war” rhetoric advanced by the Christian right in the late 1970s and ‘80s — whose effects we are still feeling today. One member of the Johns Committee was the grandfather of Katherine Harris, the Florida secretary of state who led the Republicans’ successful stealing of the 2000 presidential election outcome in Florida that put George W. Bush in the White House.

The Johns Committee quietly went out of business in 1965, leaving behind it a legacy of hundreds of broken lives and an ideology that impeded the progress toward gay and racial equality in Florida for decades afterwards. The same conservative forces that brought it to power and prominence are at work today in that state — whose Republican Legislature and governor this year abolished Sunday voting, used by black churches to assemble voters among their congregations and bus them to the polls. This makes Braukman’s meticulously researched and penetratingly told history of the Johns Committee’s war on sexual, gender, and racial equality as relevant as today’s headlines.

“Communists and Perverts Under the Palms” is thus a sterling piece of gay historiography that helps us understand how we got to where we are . It is a fascinating, hitherto hidden part of the story of politics in America that deserves to be widely known.

COMMUNISTS AND PERVERTS UNDER THE PALMS: THE JOHNS COMMITTEE IN FLORIDA, 1956-1965 | By Stacy Braukman | University Press of Florida | $69.95 | 250 pages