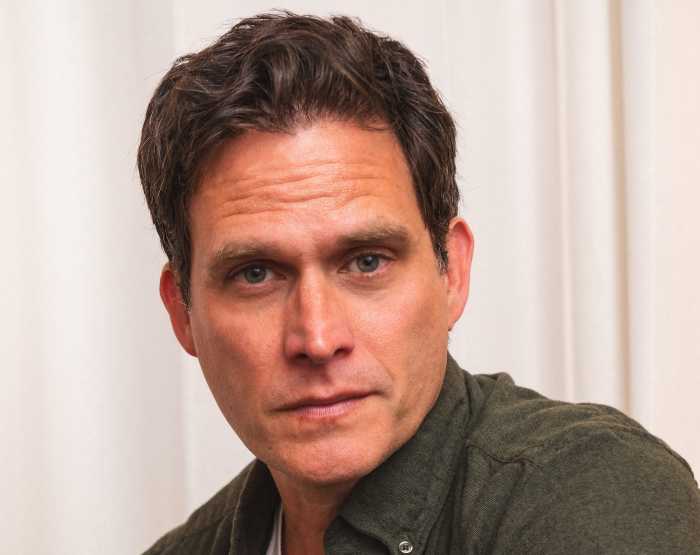

Growing up in affluent Sussex County, New Jersey, Rich Roy had a cushy life. He spent weekends playing golf and got a Camaro when he was 17. At age 19, he became a pro boxer mentored by Muhammad Ali, and later a thriving actor sharing the stage with Denzel Washington. He freely admits being “born a privileged white man.”

But one night in his 20s his luck ran out, and he found himself locked up in a holding cell with a cement floor that was covered in piss and excrement. Eventually he was shipped to the correctional facility at Rikers Island, which was 92 percent black and Latinx, where his “melanin-deprived” country club good looks made him a target. He was brutalized regularly. For the first time in his life, he learned what it was like to be a powerless minority.

The crime? A DUI — shots of Jack Daniels supercharged with a pile of coke — that resulted in the death of a young motorcyclist. One momentary lapse in judgment caused his life to spin horribly out of control.

Roy’s experience was so traumatic that he was compelled to write a theater piece titled “A White Man’s Guide to Rikers Island” (with an assist from Eric C. Webb) as a form of catharsis. The title is also the name of the tongue-in-cheek column he wrote for the prison newspaper, which proved a big hit with inmates of every stripe.

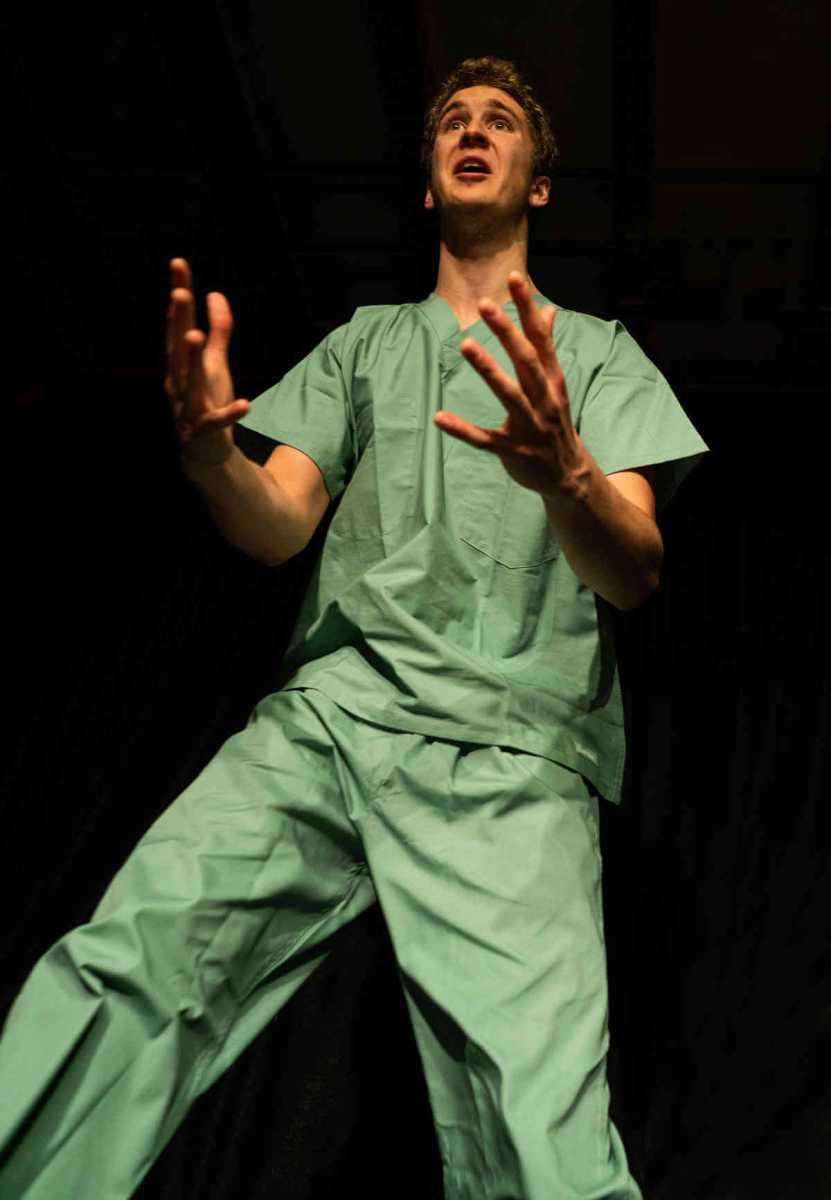

This extraordinary triumph of storytelling, now at the Producers Club theater, is a solo show of sorts where, for the bulk of the 90-minute proceedings, Connor Chase Stewart plays young Roy, recounting in gut-wrenching, lurid detail the story of how he landed in and survived one of America’s most notorious prisons. His turn is bookended by none other than Rich Roy himself, who delivers an expository intro and poignant coda to the piece.

The highly appealing, towheaded Stewart does a fine job embodying the tortured convict, wracked with guilt not just over taking an innocent life, but also about his privilege. Most inmates are at Rikers because, due to a disadvantaged background, they can’t afford bail. Roy was out on bail within 24 hours and enjoyed two years of freedom before serving time. His sentence was only several months, while most inmates are shuffled around the system for years.

The script does its best to come to terms with the race issue and Roy’s guilt.

“Even though you’re a minority in here, you get to hold onto the saving grace that you’re still a majority out there. And that means… you’re probably going to be out of this hell hole in due course. And that empty, unearned privilege is what makes everyone rightfully hate your guts just by looking at you.”

Stewart also portrays the secondary characters, though by design they are one-dimensional. There’s Shivon, his feisty heroin-addicted transgender cellmate with “great tits”; Saddam, his drug-dealing buddy; Amir, leader of the so-called Muslim Brotherhood; and his pretty wife, who ends up leaving him.

Throughout the proceedings Roy offers a shrewd glossary lesson for jailhouse neophytes, defining lingo like “flavors” (menthol cigarettes), “fish” (new guy), “shiv” (improvised stabbing weapon), and “catch some money” (ejaculate). He scrawls these key terms on a large pad of paper as if giving a college lecture.

Under the lucid direction of Thomas G. Waites, this raw, insightful drama moves at a brisk clip, and I found myself riveted on the edge of my seat. No need for elaborate sets, just a couple of chairs, an easel with a pad, an old autographed photo of Roy and Ali, and a golf club.

“I’m not supposed to be here,” Roy laments over and over.

Once he accepts that, yeah, he does belong there, he can begin to heal.

In a recent interview Roy admits he still has not fully healed. Yet he’s comforted knowing that his cautionary tale may prevent others from making the same horrific blunder. Grateful theatergoers rush up to him after the play vowing to never again drive after drinking.

A WHITE MAN’S GUIDE TO RIKERS ISLAND | The Producers Club, 358 W. 44th St. | Through Aug. 31: Thu.-Sat. at 8 p.m., Sun. at 3 p.m. | $18-$25 at awhitemansguidetorikersisland.com | Ninety mins., with no intermission