I joined the United Nations Development Program in 1973. It was the dream job I had always wanted: I would travel, live in fascinating countries, and help to make the world a better place. I couldn’t have asked for more.

The only glitch in this perfect picture was my sexual orientation. I relegated my gay sexuality to a private realm, the “closet,” but eventually my persona would emerge. How would I deal with this “abnormal” orientation? Or, more precisely, how would I be dealt with by the United Nations and my colleagues?

My first three assignments — Thailand, Myanmar and Indonesia — were “safe” posts with large offices where I was a junior staff member. With safety in numbers playing to my advantage, I could work hard during the day at the office, then disappear in the evening, enjoying my personal life.

One straw in the wind, however, was my farewell party in the United Nations Development Program’s Bangkok hub when a speech was given that ended with a humorous play on words in Thai language saying I never flirted with women. The assembled staff roared with laughter at the punch line, and although I smiled appropriately, I felt my face turning red with shame. I somehow hoped that ignoring awkward situations would cause them to go away.

Subsequent assignments in Myanmar and Indonesia were rewarding gigs — especially Indonesia, where I met the man who would become my life partner of 38 years and eventually my husband. But even in Indonesia there were uncomfortable moments in the office, reminding me that I was “different” and that even “liberal” UN crusaders could be homophobes. At an interview panel, on which I was a senior participant and interviewer, I was shocked when a colleague, also on the panel, posed a question to the interviewee, the job applicant, saying, “I see that you are 35 years old and that you are single. Can you explain WHY you are single?”

I cringed and wanted to lash out at my “fake-liberal” colleague who was often beating the liberal drum on predictable issues like anti-apartheid. But I bit my tongue and said nothing. It was a bitter lesson that told me one could be politically correct on all of the “right” issues, but still be homophobic. Back then, in the early 1980s, being gay was to be a member of a “swamp” that didn’t merit dignified consideration. Being gay was a “dirty” sexual thing.

In 1986, my next assignment as deputy resident representative in The Kingdom of Bhutan was a promotion and should have been cause for celebration, but it was where my career took a downturn. In a small post, I was now a high-profile, 46 year-old bachelor with a male partner. It was the wrong place at the wrong time. Menacing incidents began shortly after my arrival in Thimphu, the capital. My male housekeeper was brutally beaten by a Bhutanese who also happened to be a United Nations staff member. To me, this signaled a direct threat, a “warning” and a gesture of deep disrespect to my person and my official position. Not long after this beating, another insulting slight occurred. Representing the UN, I approached the Bhutanese Foreign Minister at an official reception, extending my hand to him in greeting. Without speaking a word, he turned his back to me and walked away.

I was still reeling from these incidents when my boss called me into his office saying he had received a call from our New York Headquarters. Our big boss, the director in New York, said he had received information from Bhutan that due to my promiscuous homosexual behavior, I was spreading AIDS in Bhutan. An investigation regarding this hideous rumor revealed that another staff member, disgruntled at my having disciplined him for a professional shortcoming on the job, took it upon himself to seek revenge by spreading this ugly lie about me. The upshot of the investigation resulted in my being totally cleared of any charge and the staff member terminated from his position. Even so, guilty or innocent, it was felt that my “image” had been damaged beyond repair and that my ability to hold a senior position compromised.

My Bhutan assignment was ended prematurely and I was transferred to UNDP headquarters for my final UNDP posting. My career and any further advancement were effectively dead in the water. I was not guilty of anything, but I was still tarnished by an evil, mendacious rumor.

Are there lessons to be learned from my sad, career-crushing experience? One lesson, for sure, is that “vulnerable” people, and gay people were indeed vulnerable 35 years ago, were at high risk in positions of authority when they had to exercise their power in what were often punitive situations — disciplining somebody who might lash back. There is no question, back in the day, that gay people were more subject to revenge than their straight colleagues. How “squeaky clean” does one have to be as a boss who metes out both punishment and reward? Hopefully, that was a bad old world that no longer exists, but I fear being a gay boss today still carries vulnerabilities not common to straight supervisors.

Nearly 40 years after my sad experience, it is good to see that LGBTQ people in the UN are no longer as alone and helpless as they were when I first joined the organization. Founded in the 1990s, UNGLOBE is a UN employees’ association that is active and supportive in giving LGBTQ staff members voice and greater hope for equality.

Now there is another more recent issue crucial to our financial survival. My case is currently before the UN Secretary-General and the UN General Assembly to approve pension benefits for my husband should I pre-decease him. Let’s hope that the UN will do the right thing in this case, remembering that the UN Declaration on Human Rights states that “all people have the right to marry and to equal rights as to marriage.”

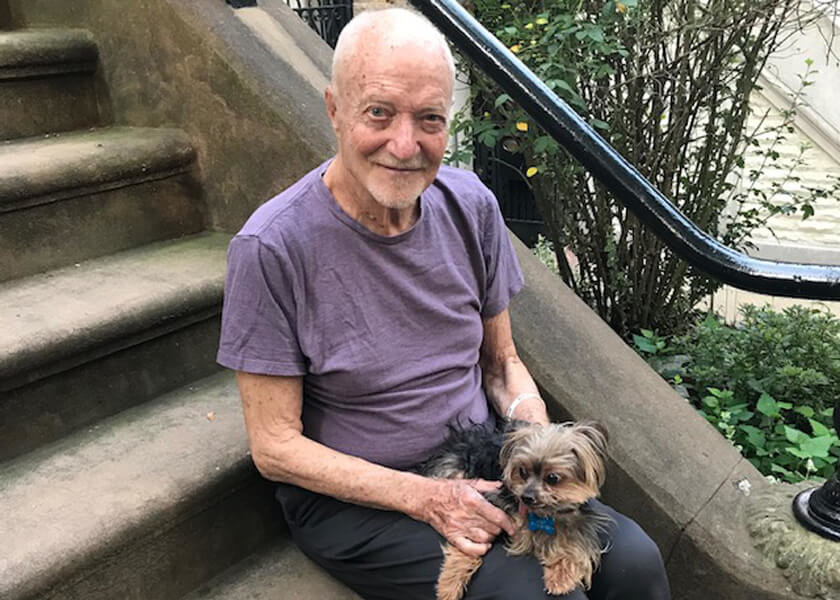

Sam Oglesby is a longtime Contributor to Gay City News and lives in the Bronx. He is an 81 year-old award-winning journalist who focuses on LGBTQ issues as they relate to older people.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter