ILLUSTRATION BY MICHAEL SHIREY

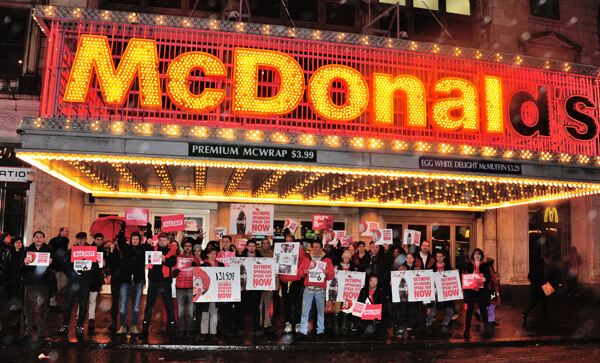

In what has become an annual tradition coinciding with the observance of International Human Rights Day at the United Nations, nearly three dozen LGBT rights advocates from across the globe traveled to New York in early December for several days of meetings and presentations coordinated through the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission.

In a Manhattan press briefing on December 9, one day ahead of the formal UN event, IGLHRC’s executive director, Jessica Stern, framed the international drive for equal rights, personal safety, and dignity as one marked by impressive progress as well as crushing episodes of backlash. The challenges around the world, she said, are diverse, complex, and often subtle.

Opening the briefing by noting the “extraordinary growth in acceptance of LGBTI rights,” Stern explained the value of activists from around the world gathering together by saying, “There are solutions. There are people who know how to end discrimination, who know how to end violence.”

For International Human Rights Day, IGLHRC convenes dozens of on-the-ground experts

But during a discussion in which representatives from Africa, the Middle East, Russia, Asia, and Latin America talked about the backlash they face at home, Stern also said, “The result of our collective audacity can be a crackdown on civil society.”

With the LGBT rights movement in the US so focused on marriage in recent years, Stern took pains to emphasize that globally “concerns are very diverse.” Activists on the ground warn their Western allies about the dangers of making aid conditional on human rights progress, they face the turmoil of civil wars and regime change, and before the legal status of couples can be broached, they must often tackle more fundamental issues such as sodomy law repeal, basic healthcare, and reproductive rights.

“We need to bring more ambition and more nuance to the work,” Stern said. “Only calling for marriage can actually hurt us.”

Chalwe Mwansa, an activist from Zambia, talked about the way backlash can become something of a contagion. His work focuses on documenting human rights abuses as well as combatting the stigma and marginalization that compromises many LGBT Zambians’ access to healthcare. Noting Zambia’s long history as a peaceful society, he said that as anti-LGBT laws and persecution have swept other African countries such as Zimbabwe, Uganda, and Nigeria –– not only at the behest of government leaders but often with the encouragement of Western religious conservatives, as well –– backlash has become a threat in his nation as well.

Humphrey M. Ndondo, who directs Zimbabwe’s Sexual Rights Centre, cautioned that the anti-gay climate in his country cannot be laid solely at the feet of its longtime president, Robert Mugabe.

“After Mugabe dies, the situation is not going to change, because homophobia has worked and has worked for years,” he said. “What works is being anti-homosexual. It sells like hotcakes.”

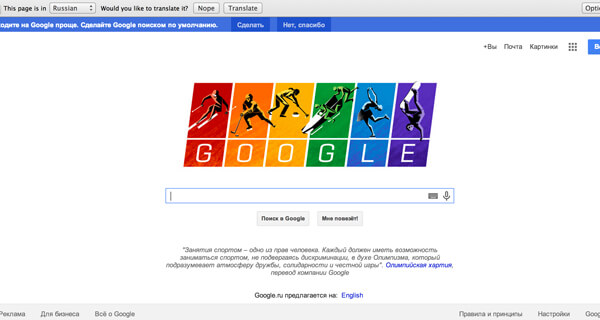

In Russia, the current crackdown on gays follows the missed opportunities of the immediate post-Soviet period, according to Daniil Khaymovich, an attorney there who works with the Transgender Legal Defence Project.

“Prior to Putin, there were 10 years or so of an independent media,” he said. “But there was no real time to create civil society institutions.” He added, “I have video from that period, where LGBT issues were discussed in a very progressive way. All these questions were then removed from media space.”

In contrast to Russia, an Egyptian activist, who cannot be named because of dangers he would face back home, challenged the notion that life for LGBT people there has changed with the succession of recent governments.

“The Mubarak regime was not secular,” he pointed out. “By constitution, Egypt is an Islamic state.”

Speaking about the recent episode in Cairo in which “33 men were arrested in a Turkish bath, beaten, and dragged outside naked” –– 26 of whom now are facing prosecution for “debauchery” –– he said it represents an effort by the government to “distract attention by claiming we challenge public morality.”

Public activism is beyond reach for now, he said. “It is not possible for anything to happen on the street because you will be killed.”

Turkish activist Sedef Çakmak. | GAY CITY NEWS

Public demonstrations for LGBT rights are also not a viable route in Turkey, though individual visibility is a path some activists are now pursuing. Sedef Çakmak talked about how she was one of a group of nearly a dozen out LGBT candidates who ran in recent local elections. Though she did not win, she now serves as an advisor on LGBT policies to the mayor of Besiktas, a municipality of nearly 200,000 within Istanbul. Though there is public debate about gay issues, there are no constitutional protections in Turkey based on sexual orientation or gender identity and a hate crimes law proposal under consideration also fails to address these categories.

Çakmak spoke movingly about the personal toll activism can take, even in a society where LGBT life is not completely hidden.

“Wherever I go I say I am an openly lesbian, but I am so afraid,” she said, her voice cracking. “ I am doing this because I am so afraid. Two weeks ago, a transgender was killed. Another friend came to my house after being beaten for being transgender. My girlfriend, who was beaten earlier, gets angry when I try to hold her hand, put my hand on her shoulder in public. It’s ironic that we talk about political representation of the LGBTI community, but we are afraid to walk on the street. We are particularly afraid of the government.”

Backlash is also apparent is countries such as Colombia, where activists are working on family issues such as partner recognition and adoption.

“We are facing very strong opposition that we did not face 10 years ago, that we need to take into account in doing our work,” said Marcela Sanchez, director of Colombia Diversa.

In Taiwan, the challenges are not so much in the public sphere, where LGBT people remain largely invisible to a public that chooses not to see them, said Jennifer Lu, director of public affairs for the Taiwan Tongzhi Hotline Association, but within their homes.

“There is violence in families,” she said, “and that is ignored because it is seen as normal. There is a family obligation to get married. There are negotiated marriages between gay men and lesbians. It happens all the time.”

Lu and her partner want to have a child and want recognition of their family. Asian LGBT groups, she said, lack resources to advance their advocacy much beyond volunteer efforts.

When asked what Western activist can do to support human rights efforts in their countries, Zimbabwe’s Humphrey M. Ndondo warned against making economic aid contingent on progress.

“Aid conditionality means Zimbabwe gets closer to China, which will not press Mugabe on this issue,” he said. “Threats from the UN and elsewhere to withdraw aid can hurt HIV prevention. Aid conditionality does not work. We have talked about this among many African activists.”

The Egyptian activist offered a different perspective on what the people in his country need from the West and the UN.

“I want member states to act strongly against Egypt,” he said. “There have been many accommodations. The UN should protect the Egyptian people.”

Russia’s Daniil Khaymovich spoke for many of the activists in saying the West can be most helpful in supporting the development of non-government civil society institutions. Russian law forbids political groups from taking money from outside the country, but support for education efforts on issues such as transgender health, in contrast, faces no such constraint.

“Educating doctors is not political,” he said, “and is invisible from the standpoint of the state.”