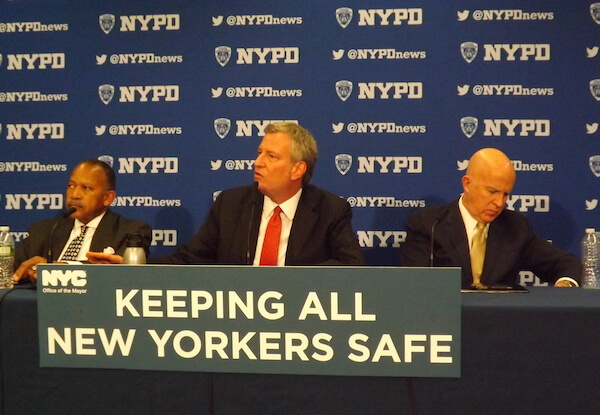

Nick Porto addresses the May 20 rally, while partner Kevin Atkins looks on. | DONNA ACETO

In the wake of the anti-gay murder of Mark Carson on May 18 and at least seven homophobic assaults across Manhattan this month, proposed initiatives to fight back have found their way into the mix along with plenty of heated rhetoric from LGBT leaders and elected officials that this “will not stand.”

At a West Village march and rally on May 20, ideas were put forward from the platform and discussed among participants in the crowd. And a new initiative to combat hate crimes has been ordered in the schools to take place before classes end for the summer in June.

It ain’t enough to chant “Hey hey, ho ho, homophobia’s got to go” and “Whose streets? Our streets!” as more than 1,500 did at Monday’s march, but a diverse turnout such as occurred does send a signal that the community is not going to slink away in fear in the face of these attacks.

Activists, government struggle to stem anti-gay crime wave

Florine Bumpars, Carson’s aunt, stirred the crowd by declaring, “We want justice served so that Mark’s death will not be in vain,” describing him as “a loving and caring person, truly loved by his mother, father, friends, and co-workers.”

Marjorie Hill, CEO of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, said, “We deserve to be out and proud on Staten Island,” likely still a tall order for those who want to walk the streets hand in hand — despite the emergence of the LGBT community there and the election of an out gay member of the Assembly, Matt Titone.

Ira Manhoff, an ACT UP veteran, wants to revive a variation of the Pink Panther community patrols that came out of Queer Nation in 1991, monitoring the East and West Village and the Ramble in Central Park after an rash of anti-gay assaults then.

Jay Kallio, a transgender man who has been an activist since 1972, attributed the current backlash to the fact that the community is “winning” the fight for equal rights. “The tragedy is that some of us are going to get hit,” he said. Indeed, Kallio called police about one bias attack he suffered on April 23 but didn’t both reporting a second one that happened this past week.

“I’m lucky to be alive,” he said. “I’m going to go out with friends more than I did before.”

For 15 years, Kallio was a member of the auxiliary police force where “I could be out there on my own behalf.” He urged others to follow suit.

Sharon Stapel, executive director of the New York City Anti-Violence Project (AVP), said “all options are on the table,” but hastened to rule out a return to the West Street Gang, immortalized by the late gay Doric Wilson in a 1977 play of that name about the true story of gay men who organized to bash gay-bashers in order to get them to stop.

“Look at how strong we are,” Stapel said. “We will not tolerate this kind of violence. You are saying you won’t take it either.”

This kind of rhetoric of community empowerment dominated the rally. Practical solutions were less in evidence.

AVP has scheduled Friday Community Safety Nights Out starting May 24 and running through LGBT Pride Month, when anti-gay violence often spikes.

A release from Speaker Christine Quinn’s office said, “AVP will conduct outreach in the affected neighborhoods to raise awareness and provide people with information and safety tips.”

The NYPD has committed to an increased police presence in the areas of the seven recent Manhattan attacks, including “setting up temporary headquarter command vehicles,” the speaker’s release said.

Quinn also announced a hate crimes public awareness campaign and a “Speak Out Against Hate Interfaith Weekend” at 50 houses of worship to take place in the near future. Some religious leaders spoke at the rally, though none were of the stripe who claim to condemn anti-gay violence even as they teach that homosexual activity is evil.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, called out by some in the crowd at the Monday rally for not being there, said the following day, “The NYPD, however, can only do a certain amount to protect New Yorkers from violence. We’ll do everything that we can and we’ll prosecute, to the fullest extent of the law, anyone who commits hate crimes. But all of us can do our part as well to end hate crimes and spread tolerance — as parents, as teachers, as friends, and as members of the community.”

Comptroller John Liu issued a statement that read, “The recent spate of anti-gay crimes tarnishes our city's reputation as a beacon of diversity and tolerance — and we must fight back by working even harder to achieve equal rights and treatment for all.”

But New York City has passed essentially all the sexual orientation and gender identity protections possible under municipal law. The key issue is implementation and on that score, the city is often found wanting.

At a press conference on May 20, hours before the West Village march, Quinn stood with Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott to announce an emergency “anti-hate crime initiative.” According to Quinn, every school is mandated to “take time out of their day and organize an event” before the end of the school year that teaches that “hate violence is unacceptable.”

“We are committed to doing what we can beyond Respect for All,” the current anti-bullying program in the schools, Walcott said. “We need to take it to the next level.”

However, details of that new program promised by the Department of Education in response to a follow-up question from Gay City News had not delivered as of press time the following evening.

Others spoke to the problems that continue on the ground in the schools.

City Councilman Daniel Dromm of Queens, an out gay former teacher, said, “I’m glad the Department of Education is doing this, but unless they tell everyone to use the words lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, the message is not clear to the students that homophobic remarks are wrong.”

Dromm also said that even today only a “handful” of LGBT teachers in the system are out to their students — a characterization Walcott disputed, noting that teachers are protected under the law no matter what their “sexual persuasion.” But teachers often shy away from being honest about their lives in ways that heterosexual teachers take for granted for fear of losing control of their classrooms and not being backed up by administrators.

Frank Jump, who teaches at PS 119, an elementary school in Brooklyn, said that while “it rarely comes up,” he will be out when a student presses him. Teaching since 2000, he was pictured on the front page of the New York Post after marrying his husband, Vincenzo Aiosa, in 2004. “They wanted to fire me at my old job,” he said. “The principal called the district office and said, ‘One of my teachers went to Canada to get married. What should I do?’ The district rep said, ‘You should congratulate him.’”

In his current job, Jump feels supported by his principal. “But I live in a bubble,” he said. “We have a great school. I imagine it is very hard to come out for most teachers.”

And, he explained, “I don’t have time to become a full-time gay teacher. I teach by example. If the Board of Ed wants to hire me to be a spokesperson for gay teachers, fine.”

Homophobia, Jump said, “has to be targeted from Day One in schools — spoken about very publicly, as embracing us the way President Obama does. We are part of the fabric of the community and not just any thread. We hold the community together.”

Marie Baker of the Lesbian and Gay Teachers Association is a librarian at Bronx In-Tech Academy and said that in 1991, when she started in the schools, telling a colleague she was a lesbian was unthinkable. She now feels “the atmosphere is better,” at least in her school, and that increasing numbers of students are also out.

Randi Weingarten, the out lesbian former head of the United Federation of Teachers, issued a directive that gay and lesbian teachers would be supported by the union, and Baker said “a statement from the chancellor would be useful — to help students and teachers come out safely.”

She complained that in the school system’s anti-cyberbullying program, “there wasn’t a specific reference to gay kids in it.” Similarly, Jump said, the mandatory AIDS curricula is woefully lacking in gay content, despite the fact that isolated LGBT youth are at highest risk for HIV.

Thomas Krever, executive director at the Hetrick-Martin Institute for LGBT youth, told me at the rally that in the schools, “I tend to think there is more of a climate to broach the subject. Now the challenge for us as adults and young people is to come out” to make it safer.

The other challenge, of course, is following through on the expectations that marches and rallies like May 20’s create. Nick Porto, who survived a May 5 attack by Knick fans outside of Madison Square Garden, worries that the sense of urgency around his case is already fading. “We don’t know what’s going on,” he said, though AVP’s Stapel, standing nearby, chimed in, “We’re going to do everything we can to follow up.”

Two years ago, at the LGBT Pride March in June, the community exploded in joy at the passage of marriage equality. When Porto had the mike at the rally, he said, “Gay rights is a lot more than just marriage.”