Aaron Blake and Andrew Garland in the New York City Opera production of Péter Eötvös’ “Angels in America,” with a libretto by Mari Mezei. | SARAH SHATZ

Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America” diptych, as I noted in a preview last month , was operatic in scale and theatrical voice to begin with. For their 2004 operatic adaptation, composer Péter Eötvös and his librettist Mari Mezei cut the massive play down from epic size to a digestible two and a half hours of music drama.

The New York City Opera local premiere production of “Angels in America: the Opera,” seen June 12 at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater, was a worthy effort and showed how far this fledgling company has grown in a few years.

Still, in my estimation, where Kushner’s play sings in soaring prose elegies, Eötvös’ opera just scores background music to a reduced text.

NYCO lends its best to problematic adaptation of Kushner classic

In an opera, music and poetry should combine to carry the story and the emotional content forward with the human voice as the leading instrument. Sometime in the early 20th century, operatic composers lost this art. Eötvös’ intricate, layered orchestrations feature unusual combinations of instruments — electric guitar, saxophones, marimba, Hammond organ, and celesta along with the usual string and woodwind instruments. Electronic amplification and sound effects augment the soloists, and a vocal trio adds commentary and atmospheric background music from the pit.

But Eötvös’ busily animated music functions as background scoring to the story like film music for a psychological thriller. Mezei cuts down Kushner’s long arioso speeches into shorter fragments, and Eötvös underscores the text rather than setting it aloft with melody. The vocal writing allows the text to come through with clarity but the melodic units are short and staccato — never developing into expressive musical structures. Likewise the vocal lines are fragmented, veering from middle register declamation to falsetto keening, from Sprechstimme and spoken lines to octave-jumping vocalise. The music works parallel to the libretto, not as its manifestation and embodiment in sound.

Mezei’s first act expertly streamlines “Millennium Approaches” to a well-constructed 85-minute drama that efficiently introduces the characters and situations. Act II, however, is a mutilated 55-minute torso of “Perestroika.” The characters of Louis Ironson and Joe, Harper, and Hannah Pitt are abruptly dropped after the death of Roy Cohn. We never see the dissolution of Joe and Louis’ affair, Harper’s recovery and rejection of Joe, or Hannah’s friendship with Prior and her personal evolution. Scenes that cry out for musical setting, such as Louis in the hospital room singing the Kaddish over Roy Cohn’s corpse while Belize steals Cohn’s hoard of AZT for Prior, are absent.

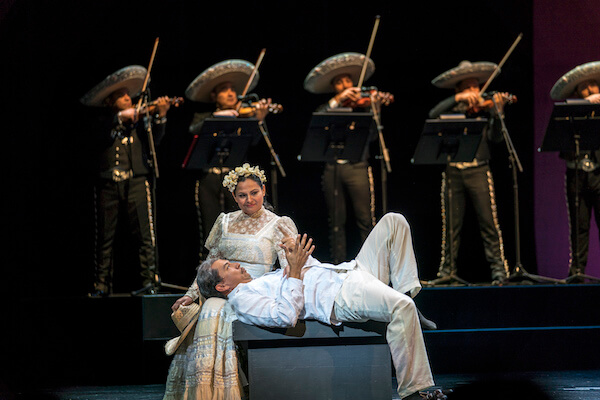

Kirsten Chambers and Andrew Garland. | SARAH SHATZ

The final two scenes include Prior’s visit to Heaven to return the book and confront the Continental Angels then skips ahead five years to Prior’s final Central Park soliloquy on the Angel of Bethesda. The ending feels abrupt, and key relationships are unresolved. The final soliloquy likewise sounds unresolved and diffuse, failing to build into a culminating musical summation of the opera’s themes and musical ideas.

City Opera, on the other hand, did itself and the work proud with a powerfully realized original production. Director Sam Helfrich’s customary use of a unit set was efficient and John Farrell’s set design — a black-tiled multi-level space — was evocative and versatile enough to suggest the wide variety of locations required by the libretto. Helfrich elicited expert acting from a group of wildly talented young American singers evoking the best New York City Opera tradition.

Two performers (both playing AIDS victims) stood out in a strong ensemble. Baritone Andrew Garland’s Prior Walter (despite a rather healthily toned physique) grew from desperation at his AIDS diagnosis to spiritual revelation and finally to strength and hope in survival. Bass-baritone Wayne Tigges captured Roy Cohn’s manic energy and animal instincts underpinned with the deep self-loathing that enabled his amoral acts. Tigges’ nasal Lower East Side “Noo Yawk” accent was as spot-on as his singing.

Kirsten Chambers’ brightly heroic soprano commanded the sustained high melismas required of the Angel. Aaron Blake found in Louis Ironson the fear, vulnerability, and insecure self-doubt that spurred his abandonment of Prior. His bright silvery lyric tenor handled Louis’ rangy music with the same adroit sensitivity. The excellent work of soprano Sarah Beckham-Turner (Harper Pitt/ Ethel Rosenberg), mezzo Sarah Castle (Hannah Pitt/ Rabbi), baritone Michael Weyandt (Joe Pitt), and countertenor Matthew Reese (Belize) made one wish their characters had been given more opportunities in Act II.

Conductor Pacien Mazzagatti and his well-rehearsed orchestra reveled in the eclecticism of Eötvös’ score, fully realizing its dramatic potential.