Tonya Pinkins embodies the fascinating, remarkable character Tony Kushner created

Tonya Pinkins is the reason to see “Caroline of Change,´ the new musical now playing at the Eugene O’Neill.

Pinkins gives a superb portrayal of Caroline, a black maid in a Jewish household in the early 1960s in a Louisiana still in the cultural throes of Jim Crow. It is a finely rendered performance of tremendous depth and sensitivity of one of the most fascinating characters in recent musicals. Caroline intrigues not merely as an individual woman but because she represents a generation on the cusp of change, as do the rest of the characters in the piece.

The larger world is on the brink of revolution, and as often happens in the midst of a dynamic shift, no one really knows what’s going on. What Pinkins accomplishes through Caroline is a balance of humanity and metaphor that is consistently engaging. More than any of the other performances in the play, Caroline must both be authentic and serve as a literary device for a world in transition. It is Pinkins’ abiding sensitivity and simple truth that allows the role to work so effectively on many levels.

The central plot point on which the entire play turns is the relationship between Caroline and the son of her employers, Noah Gellman. Noah’s stepmother, Rose, has told Caroline that she can keep any change Noah leaves in his pants when he tosses them in the laundry, a bad habit Rose is trying to break. Noah is grieving for his biological mother who died, as his father is distracted and generally distant. The key relationship is between Caroline and Noah, thrown into stark relief when Noah leaves the $20 Chanukah present he has gotten from his grandfather in his pocket. It is such a small moment, but it changes their relationship forever and imposes a distance between the two that is never really mended.

The obvious symbolism relates to the ways in which a dominant culture assuages its guilt about discriminatory practices by making token gestures. Rose says she cannot raise Caroline’s salary, but convinces herself that she is giving Caroline a raise by letting her keep the money she finds. Caroline’s unease is unmistakable, creating the dramatic tension of the piece.

That is, when it works. The book by Tony Kushner is uneven, and the tone of the drama shifts from abstraction to naturalism in ways that are sometimes disconcerting. While this is certainly Kushner’s idiosyncratic style, there are times when it doesn’t work, such as an overly long Chanukah party scene with a political argument thrown in. Such scenes seem heavy-handed and lack the fluidity of the rest of the play, such as the interactions between Caroline and Rose and between Caroline and Noah. Kushner’s lyrics are more simplistic than the rest of the writing, sometimes built on rhyme schemes that are much too obvious and out of keeping with the richer character development in the book scenes.

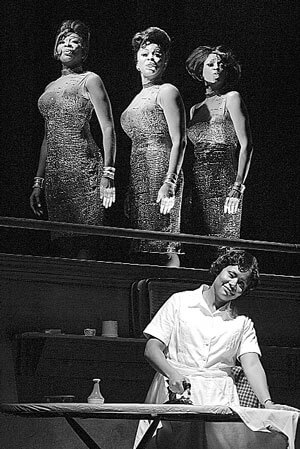

Nonetheless, the show is consistently engaging, and there are some wonderful touches like a chorus of appliances—the washing machine, the radio, and the dryer—and parts for the moon and the bus Caroline rides. All of these are ingenious ways of explicating Caroline’s world and her interior monologues, yet Kushner never achieves the same poetic heights when people are talking to people.

Despite less-than-perfect lyrics, Jeanine Tesori’s score is wonderful. Her expression of character through changing harmonics and some of her melodic lines are haunting. As she did in “Violet,´ Tesori finds musical ways of underpinning emotion and develops a kind of cumulative impression of people and events throughout the evening that is highly dramatic and often quite moving.

The company is strong. Pinkins carries the show, though she was having some vocal difficulties at the performance I saw which did not distract from the excellence of her work. Veanne Cox as Rose is excellent. After Caroline, Rose is the most complex part in the piece—a woman who is taking on fresh roles in an established order: new mother, new wife, new boss—and trying to find her way more or less on her own. Anika Noni Rose as Emmie, Caroline’s daughter, has a magnificent voice. Emmie represents the new awareness of a freer African American community in 1963, and her performance is a combination of barely contained fire, passion, and insecurity. The rest of the company acquits itself well, especially Broadway veterans Alice Playten and Larry Keith, but they, like the rest of the cast, are limited by the writing to one-dimensional roles.

Director George C. Wolfe negotiates the unevenness of the script as best he can, though the occasional bumpiness of the evening seems inevitable.

Like Kushner’s other work, it’s evident that there is a great intellect at work, yet while the end result is intriguing and intermittently affecting, there is still a lack of the sort of coherence that can offer a real emotional experience for the audience. The show ultimately keeps its distance from the audience—like the distance between Caroline and Noah—that is difficult to define, but inescapable and leaves you wanting something more.