How does a Catholic hospital system justify denying health care coverage to their employees' families?

A Manhattan judge has ruled that a woman denied employer-provided health insurance coverage for the same-sex spouse she legally married cannot sue under federal employment benefits law.

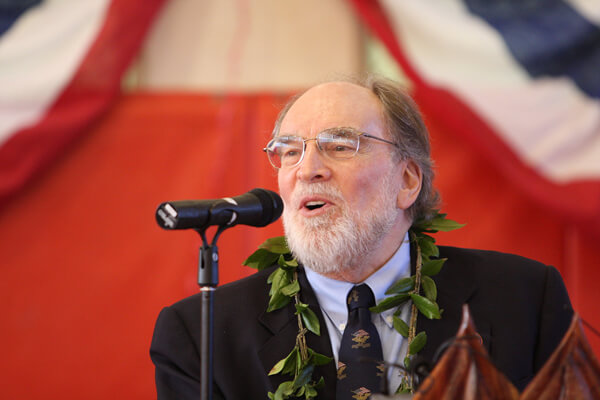

The May 1 decision from US District Judge Nelson S. Roman granted a motion to dismiss the case brought by Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield and St. Joseph’s Medical Center, a Catholic health system.

The plaintiff, identified in court papers as “Jane Roe,” has been employed at the St. Vincent’s division of St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Westchester County since 2007. After marrying her same-sex partner, she attempted to enroll her wife as a dependent, but was told by the St. Joseph’s human resources department that the plan does not cover “same-sex spouses.”

In case involving a Catholic hospital, court finds federal law, not state nondiscrimination protection, governs

In response to grievance letters filed with both St. Joseph’s and the insurer, Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield, Empire responded that “under [the Plan], same-sex spouse and domestic partner is an EXCLUSION under the benefit.”

“Roe” then filed suit in federal court, alleging violations of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), a federal statute regulating employee benefit plans of non-governmental employers. Her main argument was that because of last year’s Supreme Court ruling nixing the Defense of Marriage Act’s ban on federal recognition of legal same-sex marriages, ERISA’s non-discrimination provision mandates coverage for same-sex couples in compliance with New York law.

The hospital system and Empire, in response, argued that New York law is preempted by ERISA, and thus is inapplicable in this case. ERISA has a broad preemption provision, which holds that the federal law “shall supersede any and all state laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan.”

Judge Roman rejected the idea that ERISA would preempt New York’s marriage law, but he also asserted that issue is “irrelevant” in resolving the case.

“The question presented by Plaintiff’s Complaint is not whether ERISA or New York State law applies on the issue of marriage, but whether a private plan violates a provision of ERISA by excluding same-sex couples from beneficiary status,” he wrote.

Roman concluded that the exclusion of coverage for same-sex couples does not violate what is typically viewed as ERISA’s non-discrimination provision, a finding in line with the narrow interpretation of its requirements binding on federal judges in New York under Second Circuit Court of Appeals precedent.

The nondiscrimination provision “Roe” relied on is titled “Interference with protected rights,” and states it is unlawful to “discriminate against a participant or beneficiary for exercising any right to which he is entitled under the provisions of an employee benefit plan or for the purpose of interfering with the attainment of any right to which such participant may become entitled under the plan.”

The typical complaint this provision would cover is a situation where an employer fires somebody in order to prevent them from qualifying for benefits. The Second Circuit has said this section was “designed primarily to prevent ‘unscrupulous employers from discharging or harassing their employees in order to keep them from obtaining vested pension rights.”

Trial courts in the Second Circuit have therefore given a narrow reading to this provision.

Courts in some circuits outside the Second have taken a broader view, but Roman was bound by the Second Circuit precedent. Under ERISA, he wrote, employers are “generally free” to “adopt, modify, or terminate welfare plans” such as health insurance plans. The federal law does not regulate the “substantive content of welfare-benefit plans,” he found. Consequently, unless another federal statute — as opposed to a state enactment — would ban such an exclusion as discriminatory, a federal court would not have jurisdiction over the discrimination claim.

The New York Human Rights Act forbids sexual orientation discrimination in employment and, since 2008, has been interpreted by the state courts to require public employers to allow legally recognized same-sex spouses of their employees to participate in their insurance plans. ERISA, however, preempts the application of that law to a private employer, such as St. Joseph’s.

This gap in protections for same-sex couples could potentially be corrected if a federal Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) were enacted, though there is considerable debate among advocates about whether religious exemption language in the bill approved by the Senate last year would still give St. Joseph’s an out.

Before DOMA’s ban on federal recognition of gay marriages was struck down, ENDA incorporated that measure by reference and specifically stated it would not require employers to provide benefits to same-sex partners of employees. The current version of the bill has dropped that provision but it does broadly exempt corporations deemed to be “religious employers” under the 1964 Civil Rights Act. If St. Joseph’s Catholic affiliation allowed it to assert status as a “religious employer,” it could claim an exemption.

Legal advocacy groups have criticized this religious employer exemption as being broader than required by the First Amendment, but sponsors of the bill, including the Human Rights Campaign, argue it is necessary to secure passage of the measure, which has languished in Congress for more than two decades.

Interestingly, Roman noted that, under a different set of circumstances, ERISA might require recognition of a same-sex marriage. Last year, a federal court in Philadelphia ruled that when an employee benefit plan uses the term “spouse” without a specific definition of that term, an ERISA requirement that surviving spouses are automatic beneficiaries of a pension plan would include legally married same-sex spouses, so long as, at the time of their spouse’s death, they live in a state that recognizes their marriage.

“Jane Roe” is represented by Debra Sue Cohen, Jeffrey Michael Norton, and Randolph M. McLaughlin of the New York City law firm Newman Ferrara LLP.