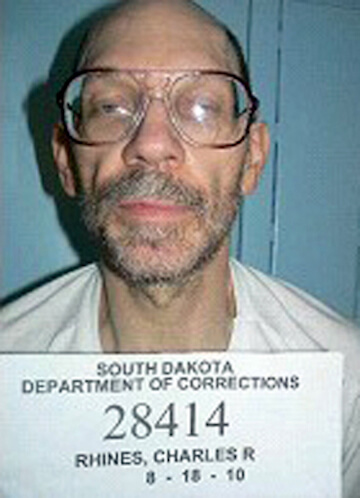

Altitude Express, which had employed the late Donald Zarda, is seeking Supreme Court review of an appeals court victory by the skydiver’s estate in a sexual orientation discrimination case involving his firing. | FACEBOOK.COM

At the end of May, the US Supreme Court had received two new petitions asking it to address the question whether the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s Title VII ban on employment discrimination “because of sex” can be interpreted to apply to claims of sexual orientation discrimination.

Altitude Express — which employed the late Donald Zarda, a skydiving instructor who claimed he was dismissed because of his sexual orientation in violation of Title VII — has asked the high court to reverse a February 26 ruling by the New York-based Second Circuit Court of Appeals that the district court had erred in dismissing Zarda’s claim as not covered under the 1964 Act. The circuit sent the case back to the district court, holding that sexual orientation discrimination is a “subset” of sex discrimination.

Gerald Lynn Bostock, a gay man who claims he was fired from his job as the Child Welfare Services coordinator for the Clayton County Juvenile Court System in Georgia because of his sexual orientation, is asking the Supreme Court to overturn an 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruling that reiterated its holding last year in Evans v. Georgia Regional Hospital that an old circuit precedent requires three-judge panels there to dismiss Title VII sexual orientation claims. As in the Evans case, the 11th Circuit refused Bostock’s request to consider the question sitting en banc with all its active judges.

Both sides of Title VII sexual orientation question seek high court review

The question whether Title VII can be used to challenge adverse employment decisions motivated by the worker’s actual or perceived sexual orientation is important as a matter of federal law, especially since a majority of states do not forbid such discrimination within their own jurisdictions. Although Title VII applies only to employers with at least 15 employee — and so leaves regulation of smaller businesses to states and localities — its applicability to sexual orientation discrimination claims would make a big difference for many lesbian, gay, and bisexual workers in much of the nation where such protection is otherwise unavailable.

Not one state in the southeastern US forbids sexual orientation discrimination by statute. In Georgia, individuals employed outside of a handful of municipalities are, like Gerald Bostock in Clayton County, out of luck unless the federal law can be construed to protect them. An affirmative ruling by the Supreme Court would be especially valuable for rural employees who are unlikely to have any state or local protection.

During the first several decades after Title VII went into effect in 1965, every attempt by LGBTQ plaintiffs to assert sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination claims was rejected by the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the agency responsible for overseeing its enforcement, and by the federal courts.

Two Supreme Court decisions adopting broad interpretations of the meaning of discrimination “because of sex,” however, have led to reconsideration of that old position. In Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins in 1989, the high court accepted the argument that an employer who discriminates against a worker because of that person’s failure to comport with expected sex and gender stereotypes may have violated Title VII.

And in Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services in 1998, the Supreme Court, holding that the interpretation of “because of sex” was not limited to factual scenarios specifically contemplated by Congress in 1964, rejected a Fifth Circuit ruling that Title VII could not apply to a case where a man was subjected to hostile environment harassment of a sexual nature by male co-workers. In that case, the court — speaking unanimously through Justice Antonin Scalia, no less! — said Title VII could be applied to “comparable evils” to those envisioned by Congress.

Taking these two cases together as precedents, lower federal courts began to interpret sex nondiscrimination laws more broadly, first in cases involving transgender plaintiffs and then, more recently, in cases involving lesbian, gay, and bisexual plaintiffs.

The EEOC embraced this movement in the lower federal courts during the Obama administration in rulings reversing half a century of agency precedent to extend jurisdiction to gender identity and sexual orientation claims.

The key sexual orientation ruling is Baldwin v. Foxx from 2015, issued just weeks after the Supreme Court’s marriage equality ruling. EEOC rulings are not binding on the federal courts, however, and the agency does not have the power to enforce its rulings without the courts’ assistance. It does, however, have power to investigate discrimination charges and to attempt to persuade employers to settle cases the agency finds to have merit. That EEOC decision encompassed protection from retaliation against employees who oppose discrimination or seek to enforce their rights.

Plaintiffs bringing sexual orientation cases in federal courts have had an uphill battle because of the weight of older circuit court decisions rejecting such claims. Under circuit court rules, old appellate decisions remain binding not only on the district courts in each circuit but also on the three-judge circuit court panels that normally hear appeals. Only a ruling en banc by an expanded or full bench of the circuit court can overrule a prior circuit precedent, unless the Supreme Court does so.

Some have argued, as the Bostock petition does, that Price Waterhouse and Oncale implicitly overrule those older precedents, including the case that the 11th Circuit cites as binding, Blum v. Gulf Oil Corporation. The Second Circuit ruling in favor of Donald Zarda’s estate specifically looked to Price Waterhouse and Oncale as well as the EEOC’s Baldwin decision to overrule several earlier panel decisions and establish a new Title VII interpretation for the federal courts in Vermont, New York, and Connecticut.

Before the Zarda decision, the only circuit court to issue a similar ruling as a result of en banc review was the Chicago-based Seventh Circuit in Hively v. Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana, in 2017. At the time of Hively, two out of the three states in the Seventh Circuit — Wisconsin and Illinois — already had state laws banning sexual orientation discrimination, so the ruling was most important for people employed in Indiana.

A three-judge panel of the Eighth Circuit, covering seven Midwestern states, most of which do not have state laws banning sexual orientation discrimination, will be hearing argument on this issue soon in Horton v. Midwest Geriatric Management, where the district court dismissed a sexual orientation discrimination claim relying on a 1989 circuit precedent.

Bostock’s petition argues that circuit courts should not treat pre-Price Waterhouse rulings on this question as binding. Under this logic, the Eighth Circuit panel in Horton should be able to ignore that circuit’s 1989 ruling, although it is more likely that success would come only from en banc review.

Altitude Express’s petition, by contrast, relies on the Supreme Court’s general disposition against recognizing “implied” overruling, the company arguing that the Second and Seventh Circuits erred in interpreting Title VII to apply to claims that Congress did not intend to address when it was passed in 1964, and that neither Price Waterhouse nor Oncale has directly overruled the old circuit court precedents. While the Altitude Express petition states sympathy, even support, for the contention that sexual orientation discrimination should be illegal, it lines up with the dissenters in the Second and Seventh Circuits who argued that it is up to Congress, not the courts, to add “sexual orientation” through the legislative process.

A similar interpretation battle is playing out in the circuit courts of appeals concerning gender identity discrimination claims. However, plaintiffs are having more success with these claims than with sexual orientation claims because it is easier for the courts to conceptualize gender identity — especially in the context of transition — as non-conformity to gender stereotypes, and thus addressed specifically by Price Waterhouse. Although only one circuit court — again, the Seventh — has gone so far as to embrace the EEOC’s determination that gender identity discrimination claims can be considered straight-up sex discrimination without resorting to a stereotyping theory, most courts of appeals that have considered the question have agreed that the stereotyping theory suffices to allow transgender plaintiffs to pursue Title VII claims in federal court.

Many have also applied the stereotyping theory under Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 to find protection for transgender students.

If the Supreme Court were to take up the sexual orientation issue, a resulting decision could have significance for gender identity claims as well, depending on its rationale in deciding the case.

The timing of these two petitions, filed late in the current high court term after all oral arguments have been concluded, means that if the court wants to take up this issue, the earliest it could be argued would be after the new term begins on October 1. As of now, nobody knows for certain what the composition of the court will be when the new term begins. Rumors of the possible retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, who turns 82 in July — likely to be the “swing” member on this as on nearly every LGBTQ rights case to date — are rife, and although Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who recently turned 85, and Stephen Breyer, who turns 80 in August, have expressed no intentions of stepping down, they are — together with Kennedy — the oldest members of the court.

Justice Clarence Thomas, a decisive vote against LGBTQ rights at all times, was appointed by President George H.W. Bush in 1991 and is the second-longest serving member of the court after Kennedy (a Reagan appointee in 1987). But Thomas, who was relatively young at his appointment, will turn 70 on June 23 — and most justices have continued to serve well past that age — so the occasional speculation about his retirement is probably premature.

If the justices are thinking strategically about their votes on taking controversial cases, they might hold back from deciding whether to grant these two petitions until they see the lay of the land after the court’s summer recess.

The Altitude Express petition was filed by Saul D. Zabell and Ryan T. Biesenbach of Zabell & Associates, P.C., in upstate Bohemia. The Zarda Estate is represented by Gregory Antollino and Stephen Bergstein of Bergstein & Ullrich, LLP, of New Paltz. The Bostock petition was filed by Brian J. Sutherland and Thomas J. Mew IV of Buckley Beal LLP of Atlanta.

The Trump Justice Department sided with Altitude Express in the en banc argument in Zarda before the Second Circuit, while the EEOC, with the majority still made up of Obama appointees, sided with the Estate of Zarda. The Bostock petition seizes on this divided view from the government representatives in Zarda as yet another reason why the Supreme Court should take up the issue and resolve it once and for all.