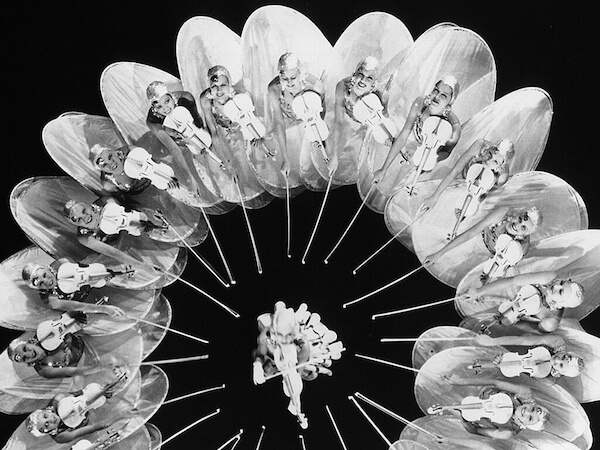

Chorines in Mervyn LeRoy’s “Gold Diggers of 1933.” | FILM FORUM

Although it was said he never had a dance lesson in his life, the most famous choreographer in cinema has got to be Busby Berkeley (1895-1976). As a holiday treat, Film Forum is hosting a festival devoted to him, filled with those signature, splashy, overhead aerial shots – that made his reputation – of kaleidoscopic patterns formed by human bodies (209 W. Houston St., through Dec. 15; filmforum.org/series/busby-berkeley-series).

The child of a single actress mother, he choreographed on Broadway in the 1920s and got his movie start with Samuel Goldwyn, working on the early talkie Eddie Cantor musicals. (Among those being shown is a childhood favorite of mine, “Roman Scandals” (1933; unfortunately already screened on Dec. 7, with its gleaming Deco ancient era look and the delectable young Gloria Stuart, the gay leading man, handsome David Manners, and cherishable torch singer Ruth Etting performing “No More Love” against a background of downcast slave girls, one of them a very young Lucille Ball.)

Berkeley’s most famous films are present and accounted for: “42nd Street” (1933; Dec. 10, 12:30, 4:25 & 8:20 p.m.; Dec. 13, 2:35 p.m.; Dec. 15, 12:30 p.m.), which really made his career, bringing musicals back into vogue after too many of them turned off the public, and remains as compellingly entertaining with its cliché-rife plot – clichés, by the way, that were endlessly repeated in other musicals precisely because they were so fabulous. Besides those famous geometric set pieces and the title song, staged to present a splashy, gritty picture of Times Square, complete with the murder of another Berkeley specialty, the nubile chorine, the film features the sumptuously gifted star Bebe Daniels, who introduces “You’re Getting to Be a Habit with Me,” which she sings twice, each with a glamorous nonchalance that marks a true superstar diva. Harry Warren and Al Dubin wrote the songs as they did for most of Berkeley’s Warners films, filling the screen and audience ears with fecund, irresistibly catchy melody and snappy lyrics.

Movies’ most famous choreographer; a Puerto Rican dancer and national treasure

That other classic, “Gold Diggers of 1933” (1933; Dec. 11, 12:30, 4:30 & 8:30 p.m.), is here, with Ginger Rogers, clad in Orry-Kelly coins, singing “We’re in the Money” in pig Latin, and her gorgeous partners in grift, cherubic Joan Blondell and stately, wonderfully versatile Aline MacMahon.

In the terrific “Footlight Parade” (1933; Dec. 11, 2:25 & 6:25 p.m.; Dec. 12, 12:40 p.m.), James Cagney gets to show off his musical chops, namely his oddly staccato style of dancing, and in “Shanghai Lil,” one of the film’s “prologues,” he plays a soldier off to war, leaving behind his chattering sing-song girl (the always inept, yet somehow endearing Ruby Keeler in yellowface, adrift in a Burbank opium den).

“Gold Diggers of 1935” (1935; Dec. 14, 12:30, 4:15 & 8 p.m.) contains Berkeley’s most justly celebrated number, the dazzlingly Expressionistic “Lullaby of Broadway,” throatily warbled by talented, woefully underused Hawaiian starlet Wini Shaw.

Dick Powell and Dolores del Rio in Douglas Sirk’s “Wonder Bar.” | FILM FORUM VIA PHOTOFEST

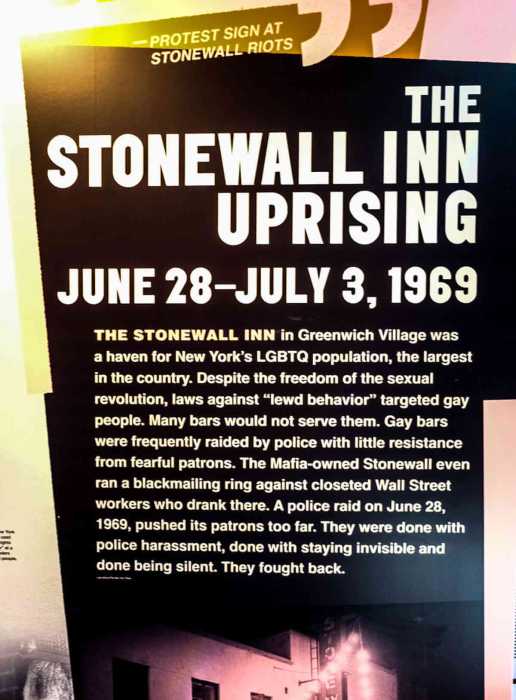

But this festival is awash in rarities, too, like “Wonder Bar” (1934; Dec. 14, 2:25, 6:10 & 9:55 pm.), rarely revived today because of its blatant racial stereotyping, which at one point depicts heaven for black folk as largely a matter of watermelon eating. Apart from that, it’s a pretty splendid entertainment, thrillingly Deco-designed, showcasing Al Jolson at his ebulliently brash – if at times, questionable – best, Dick Powell singing the lovely “Don’t Say Goodnight,” and that always agreeably sleazy sheik Ricardo Cortez (nee Jacob Krantz), two-timing two physically similar brunettes, Dolores del Rio and Kay Francis, both at their most gorgeous. As queer history goes, the film is notable for a scene in which a man asks a couple on the dance floor if he can cut in, only to take up with the man, not the woman, as an observing Jolson flaps his wrist and cries, “Woo woo!”

The beyond-exotic del Rio also stars in “In Caliente” (1935; Dec. 15, 2:35 & 6:40 p.m.), quite negligible apart from the number introducing maybe the catchiest song ever written, “The Lady in Red,” again warbled by the effervescent Shaw.

In “Fashions of 1934” (1934; Dec. 8, 2:20, 5:50 & 9:20 p.m.), you will see why Bette Davis had really no choice but to become the groundbreaking, mannerism-wielding, always slightly bizarre great actress that she evolved into, for here a clueless Warners tried to turn her into Garbo. As a piratical designer for a New York dress house, surreptitiously snapping shots of the latest haute couture in Paris for knock-offs, she wears a shoulder-length platinum blonde bob, with her eyelashes caked in mascara and mouth an emphatic scar (which she would later retain). It’s really a nothing part, otherwise, in a nothing froth of a movie, in which even the great designer Orry-Kelly came a cropper as did so many other costumers when called upon to do fashion shows – see Adrian in “The Women” or Bernard Newman in “Roberta,” as well. They can’t help but overdo it, and their onscreen collections slide into the vulgar or outlandish.

“Night World” (1932; Dec. 12, 2:45, 6 & 9:10 p.m.) is a very satisfying, raunchy Pre-Code romp, all of it taking place, Grand Hotel-style, in a Prohibition nightclub. Talented Mae Clarke and Lew Ayres lead the cast, which also includes Boris Karloff playing a pivotal character ironically called Happy MacDonald.

After his Warners stint, Berkeley moved over to MGM, where he directed the engaging “For Me and My Gal” (1942; Dec. 13, 6:45 p.m.), some Mickey Rooney-Judy Garland musicals, as well as Esther Williams’ soggy vehicles, and his sometimes-abusive taskmaster directorial style rubbed some stars the wrong way (Garland had him removed from “Girl Crazy.”) At Fox, he made “Down Argentine Way,” with perhaps the single campiest musical number of all time, “The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat,” revealing Carmen Miranda, flanked by every size of Technicolor phallic bananas imaginable.

With the demise of the big studio musical genre in the 1950s, work dried up for him, with “Jumbo” being his last choreographic movie credit. But in the 1960s, revivals of his films in a nostalgia craze brought his name into the limelight again and, in 1972, he choreographed the Broadway show “No, No Nanette,” with two Warners alumni, Keeler and rambunctious Patsy Kelly.

Personally, Berkeley was a complex guy, married six times and a heavy drinker. He suffered from manic depression and tried to commit suicide on at least one occasion. In 1935, he was the drunk driver responsible for an automobile accident in which two people were killed and five seriously injured. After the first two trials for second-degree murder ended with hung juries, he was acquitted in a third trial.

Debbie Reynolds worked with him and recently recalled, “He would drink a little bit, to say the least. He’d shoot these wonderful shots where they’d put him on a camera and send him 100 feet in the air, and they would tie him on, because he often fell off, and of course almost killed himself. But he’d get back up and have another bottle, and so we finally learned to sing, ‘Somewhere there’s Busby, how high the boom!’ So it just became a joke, after a while. We didn’t pay any attention to him. If he fell off, we’d just run forward and catch him.”

Let’s let the man I consider the greatest director of film musicals, Stanley Donen, have the final say here: “The funniest thing is not who influenced me positively, but who influenced me negatively. I had such an aversion to what Busby Berkeley did; in my early formative years, I thought it was terrible. Now, I think it’s wonderful. But then, I wanted to do anything but what Busby Berkeley did.”

Chita Rivera, at 83, had her Carnegie Hall debut on November 7. | CARNEGIEHALL.ORG

Another seminal dance figure, Chita Rivera, made her solo debut at Carnegie Hall on November 7. It seemed like every gay man in New York packed the place, greeting this ultimate Broadway veteran with the kind of nigh-hysterical love that only divas of the very highest order can elicit. Looking almost monotonously spectacular at age 83, Rivera worked that Carnegie stage six ways from Sunday, singing and dancing her heart out in what was basically an enlarged version of her act I caught at the Carlyle earlier this year.

Joined at times by Andy Karl, the ubiquitous Alan Cumming, Stevie van Zandt, and the New York Gay Men’s Chorus, she really rang in the holiday season with style, and I have only kudos for her and Daniel Nardicio, who has made the most amazing impresario progress, from throwing the funnest Underwear Parties ever to producing A-list spectacles like this. Bravi!