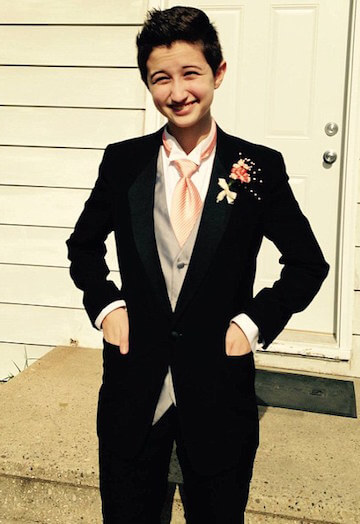

Plaintiff Ash Whitaker. | FACEBOOK.COM

Within days of each other, two federal district judges issued preliminary injunctions requiring public schools to allow transgender students to use restrooms consistent with their gender identity.

Judge Algenon L. Marbley of the Southern District of Ohio, based in Cincinnati, issued his order on September 26 against the Highland Local School District, near Akron, on behalf of a “Jane Doe” 11-year-old transgender student.

Judge Pamela Pepper of the Milwaukee-based Eastern District of Wisconsin, issued her order on September 22 against the Kenosha Unified School District on behalf of Ashton Whitaker, a transgender male high school student.

Ruling out of Ohio sharply challenges Texas court’s nationwide halt to Obama administration policy

Although both cases are important — producing essentially the same results under Title IX of the 1972 federal Education Amendments and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment — Marbley’s ruling is more significant because he sharply questioned whether Judge Reed O’Connor of the Northern District of Texas had jurisdiction when he issued a nationwide injunction on August 21 ordering the Obama administration to refrain from initiating investigations or enforcing its Title IX interpretation of gender identity discrimination.

O’Connor ruled in a case initiated by Texas in alliance with many other states challenging the validity of the federal government’s “rule” that Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination by educational institutions receiving federal funds, prohibits gender identity discrimination and requires schools to allow transgender students to use bathroom facilities consistent with their gender identity.

Neither the Highland nor Kenosha cases were affected by O’Connor’s order in any event, since they involved complaints filed by the individual plaintiffs, not by the Department of Education, which was the among the federal government targets of the Texas court’s injunction.

In the Highland case, the dispute arose when the school refused to allow the 11-year-old transgender girl to use the girls’ restrooms and the federal Department of Education became involved. The school district, abetted by Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), the Christian law firm providing representation in a number of cases challenging the administration’s position, rushed into federal district court to sue the DOE.

As the case progressed, Jane Doe’s parents moved to intervene as third-party plaintiffs against the school district. ADF sought to include many of the states that are co-plaintiffs in the Texas case and a clone case brought in Nebraska as amicus parties. Meanwhile, pro bono attorneys from Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, a Washington, DC, firm, organized an amicus brief by school administrators from about 20 states in support of Jane Doe.

Allowed to intervene, Doe sought a preliminary injunction requiring the Highland schools to treat her as a girl and allow her to use appropriate restrooms.

Marbley agreed with the federal government’s argument that the Highland school district was not yet in the position to challenge the administration’s policy because there had been no final ruling that it faced a cut-off in federal funding for violating the gender identity nondiscrimination requirements mandated by the Department of Education. A school district is in no position to file a lawsuit directly in federal district court challenging the administration’s interpretation of Title IX, Marbley found.

In reaching this conclusion, Marbley rejected O’Connor’s finding that he had jurisdiction to hear the Texas case.

“The Texas court’s analysis can charitably be described as cursory,” Marbley wrote, “as there is undoubtedly a profound difference between a discrimination victim’s right to sue in federal district court under Title IX and a school district’s right to challenge an agency interpretation in federal district court.”

Marbley also rejected the Highland school district’s argument that once Jane Doe intervened, that provided a basis for the court to assert jurisdiction over the school district’s claim. The school district, he found, could raise its arguments against the Obama administration’s Title IX interpretation in response to Jane Doe’s lawsuit, and need not maintain a lawsuit of its own.

The school district’s complaint, he concluded, should be dismissed on jurisdictional grounds — as it should have been in Texas.

In both the Highland and Kenosha cases, transgender students’ attorneys argued alternatively under Title IX and under the Equal Protection Clause. Because gender identity discrimination is a form of sex discrimination, they asserted, their Equal Protection claims should receive the “heightened scrutiny” courts apply to sex discrimination claims, which throws the burden on school districts to show they have an exceedingly important interest substantially advanced by their bathroom bans.

Both federal judges found that the transgender plaintiffs were likely to succeed on the merits of their claims under both Title IX and the Equal Protection Clause and that they were suffering harm that outweighed any the school districts might claim. While Marbley applied heightened scrutiny to his analysis, Judge Pepper, more conservatively, reached her conclusion by applying the more deferential test that required the school district merely to provide a rational basis for its policy. Even so, that policy was found lacking in merit.

Significantly, in applying heightened scrutiny, Marbley looked to the 2015 Supreme Court marriage equality ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges and its “emphasis on the immutability of sexual orientation and the long history of anti-gay discrimination.” He concluded that immutability and a history of discrimination were significant factors in the Highland case, as well.

Both the Ohio and Wisconsin judges also accorded great weight to the Obama administration’s guidance on gender identity discrimination and the Richmond-based Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling in the Gavin Grimm case that district courts should defer to it. Marbley and Pepper both rejected the argument that because Congress in 1972 did not intend to ban gender identity discrimination, administrators and judges decades later could not adopt such an interpretation of the phrase “discrimination because of sex.”

The Supreme Court has stayed the injunction that Grimm won while it decides whether to review the case, but Marbley rejected the school district’s argument that the stay “telegraphed” that the Supreme Court would take it up.

“Even if Highland has somehow been able to divine what the Supreme Court has ‘telegraphed’ by staying the mandate in that case, this Court unfortunately lacks such powers of divination,” he wrote.

Marbley also credited the arguments made by the school administrators who signed the amicus brief saying they have allowed transgender students to use appropriate facilities — something they see as necessary for their mental and physical health — without creating any problems.

Marbley’s in-depth analysis of the jurisdictional issues provides a roadmap for a challenge to Judge O’Connor’s nationwide injunction on the Obama administration’s Title IX guidance before the Houston-based Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Marbley was appointed to the district court by President Bill Clinton, while Pepper is an appointee of President Barack Obama.