Tere Connor’s uses a childlike metaphor to press a mature point

If there’s a notable trend in so-called downtown dance, it would be the exploration or questioning of ontologies. Pressed up against the glass of the media screens, we have involuntarily become aware of how our own physicality resists—and desires—simulation. Questions arising from that awareness are now pouring into live performance, which traditionally has shown peculiar resistance to hegemony and media hype. Where does being end and performance begin? In an age when everyone has their own reality show, the answer becomes much more elusive. We are way beyond Erving Goffman now.

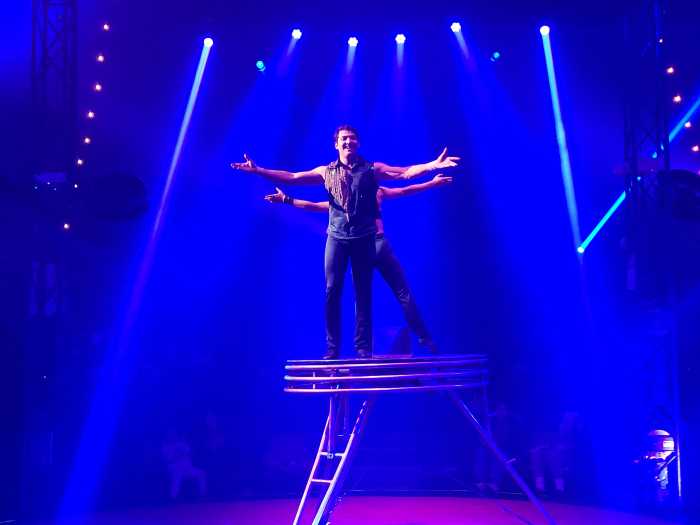

“Frozen Mommy,” Tere O’Connor’s wonderfully childlike new work of art, performed December 2 to 11 at the Kitchen, begs the question in a manner that is humorous, poignant and intellectually stimulating—the way that you think about a punch in the stomach or severe head trauma after it’s happened to you. This brilliant, moving piece mixes reality with performance and blurs the line with outstanding dancing and sincerity from Christopher Williams, Matthew Rogers, Hilary Clark, Heather Olson and Erin Gerken. They are real people in an exaggerated space, and they are faking it at least some of the time—fake smelling, fake laughing and the like.

The dancing is almost a parody of itself, balletic but with a marionette-like quality, as if the dancers do not control their own actions when they dance. Indeed, they have been directed to do so. In one repeating phrase, they move with zombie arms, while their shoulders and hips all loose give this universal motif a kind of Charlie Brown lightness.

The score by O’Connor and James F. Baker is a blend of sounds and music that is out of synch, connecting distantly with the action. Vocal interjections—expletives, names, screaming, poetry, singing, much of it madcap—couple with repetitive movement and phrases in rich and meaningful ways, always shifting and pasting together the terrain of the real and the presentational. Unison sections are particularly lush with a rhythmic one-two punchiness expressed with long balletic lines, odd, functional gestures and verbal beats.

Sometimes the humor pushes itself too far, but in the end the 180-degree flip dares you to deny a single moment of what has gone before. If performance is a shield against vulnerability and fear, it is a shield that cannot hold forever. The dancers stand in their obviously final pose for what seems like an eternity, their realness becoming ever more apparent every second even as our own discomfort surges. Rogers embodies their vulnerability falling to the floor, sobbing, as the lights finally begin to fade.

Applause seems like the wrong response. You want to hug them, kiss them, wash their feet with your hair.