New book completes the Hepburn portrait A. Scott Berg left sketchy

Thirteen days after the death of Katharine Hepburn last year, celebrity biographer A. Scott Berg published “Kate Remembered,” reflecting 20 years of interviews with the legendary screen luminary. Almost immediately, The Advocate labeled the tome, “a mixture of cautious disclosure and obsequious deference” and threw down the gauntlet for someone willing to go behind the carefully constructed public persona Hepburn protected throughout her eight decades in film.

Celebrity exposé author Darwin Porter accepted the challenge, and this Valentine’s Day, released “Katharine the Great: A Lifetime of Secrets Revealed,” a mammoth volume presenting a wealth of evidence that the late, great Kate was not necessarily straight.

In this 570-page unauthorized biography, Porter delves into the spicy sexual conquests of the Connecticut born and bred actress and her cadre of high-profile companions.

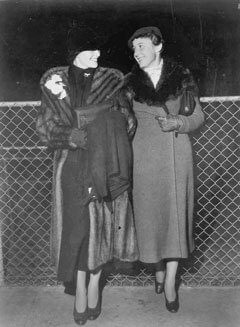

Although Porter looks at Hepburn’s early childhood, the suicide of her brother Tom, her marriage to “Luddy,” Ludlow Ogden Smith, and her career, he focuses largely on the relationship between Hepburn and American Express heiress Laura Harding. The wealth of evidence he provides indicates Hepburn was indeed bisexual, or a “double-gater” as it was called then, and that she and Harding conducted a closeted, long-term relationship from 1928 until Harding’s death in 1994, a relationship that overlapped with her seven-year “lavender marriage” to Luddy that began the same year.

It is difficult to imagine that, even in the 1930s, it was customary for a new bride and groom to bring companions on their honeymoon, as did Hepburn with Harding, and Luddy with his longtime companion Jack Clark.

Even Berg’s more discrete bio mentions Harding, noting that, after her marriage to Luddy, Hepburn moved to Hollywood and “continued to live quietly in the hills with Laura Harding (furthering speculation of a lesbian relationship).”

Hepburn’s longtime relationship with Spencer Tracy seems to have found her in more of a caretaker role than that of a lover. Berg notes that, “As she told me that first night in Fenwick [where her Connecticut home was located], ‘I never wanted to marry Spencer Tracy.’”

But then Hepburn, her first marriage notwithstanding, was not much the marrying kind, reputed instead to be partial to 10-day, whirlwind relationships with her peers in the film industry. Among those Porter names are film editor Jane Loring, actresses Greta Garbo, Billie Burke, and Elissa Landi, writers Suzanne Steele and Ernest Hemingway, and directors George Stevens, Jed Harris, and John Ford, as well as more lengthy relationships with her agent, Leland Hayward, millionaire playboy Howard Hughes, and Tracy.

Hepburn’s liberal view of relationships likely originated in her upbringing, as the child of Dr. Thomas Hepburn, a specialist in venereal diseases and an unapologetic nudist, and Kit Hepburn, an outspoken advocate for birth control.

Berg also concedes evidence of Hepburn’s bisexuality. During a visit to Hepburn’s Turtle Bay residence, Irene Selznick, David O. Selznick’s wife and Louis B. Mayer’s daughter, encountered a young woman staying there, and “her eagle-eyes witnessed an exchange between the two of them that suggested a level of intimacy she had never allowed herself to believe. ‘Now everything makes sense to me… Dorothy Arzner, Nancy Hamilton—all those women. Laura Harding. Now it all makes sense. A double-gater.’”

But Hepburn was among the most private women in Hollywood. Porter recounts a conversation between her and producer Pandro S. Berman, during which he warns her to keep her orientation quiet, saying, “If there’s a lesbian scandal about you, it could sink our ship.” According to Porter, Hepburn responded, “‘Trust me Pandro… I am not a lesbian,’“ to which he reportedly responds, “‘Perhaps you are not a lesbian. But you didn’t deny that you’re bisexual.’”

“Katharine the Great” takes an in-depth look at a Hepburn the public never knew, presenting information gleaned from interviews with Joan Crawford, Tallulah Bankhead, Patricia Peardon, Truman Capote, Garson Kanin and his wife Ruth Gordon, Hepburn’s “deflowerer” Kenneth MacKenna, and set designer Stanley Haggart.

The conclusion that Hepburn set the terms of Berg’s biography is inescapable. But we must also concede that the work of a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer who spent weekends with Hepburn from 1983 until her death offers more than a few insights about her nevertheless.

But where Berg keeps silent, Porter revels in exposing the colorful underbelly of Hollywood at its most exclusive heights, and he does not disappoint in “Katharine the Great.”

It is sobering to think that a woman who used her fame to make incredible strides for the female sex would do nothing for the gay rights struggle. But stars of the silver screen have been historically silent on matters of homosexuality, and the much maligned and misunderstood bisexual has often been made to feel the outsider.

For fans of Hepburn, both “Kate Remembered” and “Katharine the Great” have a lot to offer. Taken in tandem, the two paint the most complete —if not always the most flattering—picture of this legendary recluse to which the public has ever been privy.