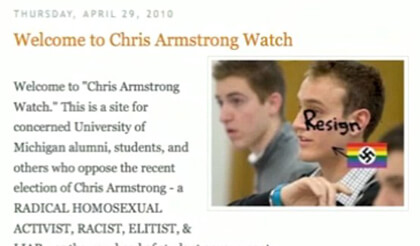

While an assistant attorney general for the State of Michigan, Andrew Shirvell took aim at Chris Armstrong, then a gay student leader at the University of Michigan.

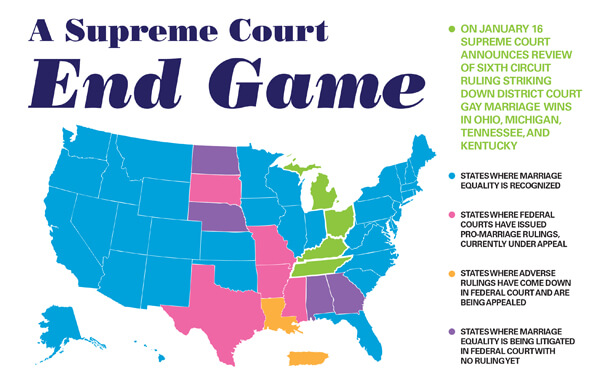

BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD | Just weeks ago, Michigan’s Court of Appeals dealt two strikes against former Assistant Attorney General Andrew Shirvell, rejecting his challenge to his dismissal by the state’s former attorney general, Mike Cox, and denying his claim for unemployment benefits. On February 2, he suffered a third strike at the hands of the US Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, based in Cincinnati.

Shirvell — who, while in the state’s employ in 2010, undertook an obsessive campaign to discredit the out gay president of the student government association at the University of Michigan, his alma mater — was found, in a ruling from the state appeals court, to lack any First Amendment free speech claim in connection with his firing. The federal appeals court, meanwhile, upheld a substantial damage award for his attacks on Christopher Armstrong, who was the first openly LGBT student government president at Michigan.

The court approved a damage award of $3.5 million against Shirvell.

Sixth Circuit upholds substantial damage award against obsessively anti-gay former Michigan official

Armstrong sued Shirvell on claims including defamation, “false light” invasion of privacy, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and stalking. The trial judge rejected Shirvell’s motion for a summary judgment dismissal, Shirvell formally refused to retract various statements he had made about Armstrong, and the case went to trial in August 2012. The jury found Shirvell liable in connection with Armstrong’s claims, awarding him $4.5 million in total damages.

Shirvell’s appeal attacked every aspect of the verdict, arguing his conduct and speech were protected by the First Amendment, that the evidence did not support the jury’s conclusions, and that the trial judge’s instructions misled the jury into awarding excessive damages. Writing for the Sixth Circuit panel, Judge Julia Smith Gibbons found merit in only one of Shirvell’s objections — that inaccuracies in the trial judge’s jury charge led the jury to impose duplicative defamation damages.

On the merits of the case, the appeals panel found that the trial record fully supported the jury’s conclusions. Regarding the defamation claim, for example, Gibbons wrote, “The evidence in Armstrong’s favor — demonstrating harm caused by statements that were properly submitted to the jury as defamatory — was immensely one-sided. Through a special verdict form, the jury found over 100 statement by Shirvell defamatory and over 60 of those defamatory statements were made with actual malice.”

“Actual malice” is a legal term of art indicating the jury found that Shirvell knew the statements were false or acted with reckless disregard about whether they were true. The court found plenty of evidence in the trial record to support the jury’s conclusion on this score.

“A reasonable jury could conclude from the evidence that many of Shirvell’s statements were pure fabrications,” Gibbons wrote. “For example, he claims that police ‘raided’ Armstrong’s house during a party, but the evidence contradicted this. A reasonable jury could conclude that Shirvell — who was standing outside, filming the house — simply fabricated his story.” She described Shirvell’s attempts to minimize some of the evidence as “disingenuous” and “implausible.”

The court also rejected Shirvell’s attempt to argue that Armstrong, as the Michigan student government president, was a public figure. Supreme Court precedents make it extremely difficult for a public figure to win damages for defamation, requiring a finding of “actual malice” — which the jury did, in fact, find here. In any event, the appeals court disagreed with Shirvell’s characterization of Armstrong. A student body president is not a public official or a government spokesperson, and the court concluded that Armstrong even fell short of the category of “limited public figure” — for having thrust himself forward into a public controversy. The only controversy in this case, the panel found, was created by Shirvell, not Armstrong.

Shirvell also claimed Armstrong failed to prove he suffered any real injury as a result of Shirvell’s actions, but the court found plenty of evidence to support the jury’s conclusion that Armstrong was entitled to compensatory damages. Having found that some of Shirvell’s statements fell into the category of per se defamation — statements presumed to inflict injury, such as, for example, tarring Armstrong as a racist, a liar, and a Nazi — the jury could award compensatory damages without specific evidence that Armstrong had suffered physically, emotionally, or financially.

Beyond that, wrote Gibbons, the jury could have found that Armstrong did suffer actual losses. It appears possible that Shirvell’s activities contributed to Armstrong’s rejection by the Teach for America program, and distracted him sufficiently during his job search to interfere with his obtaining employment after graduation. Armstrong ended up taking unpaid internships while continuing to look. Although he had a modestly-compensated job by the time of trial, Armstrong testified about his concern that the case’s notoriety would adversely affect his future job searches.

There was also “significant evidence of the emotional harm that Armstrong suffered,” Gibbons wrote, so the court upheld the award of both compensatory damages and punitive damages.

The appeals panel, however, agreed with Shirvell that the award of damages for defamation and false light invasion of privacy — two theories so highly related that the plaintiff may “have but one recovery for a single instance of publicity” under Michigan precedent — led the jury to incorrectly double up the damages related to certain of the former assistant attorney general’s statements.

As a result, Armstrong’s total award was reduced from $4.5 million to $3.5 million. Neither of those sums seems likely ever to be actually collected by Armstrong, unless the hapless Shirvell suddenly becomes a fabulously wealthy Internet entrepreneur. At this point, the verdict seems more about symbolic vindication.