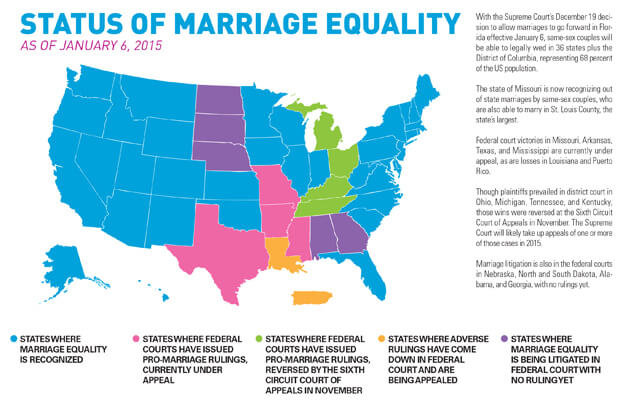

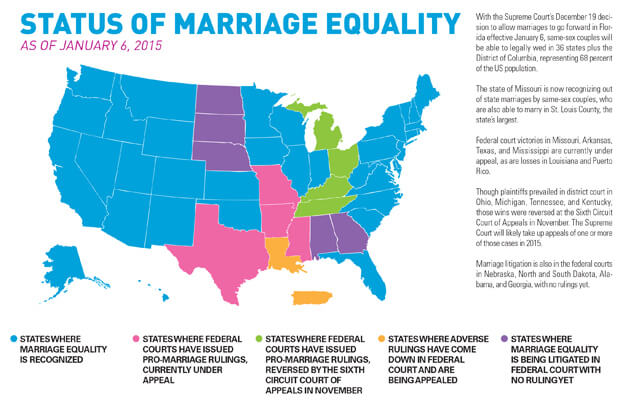

With the Supreme Court's decision to let the stay on a marriage equality ruling in Florida expire on January 5, the map on January 6, 2015 will look like this:

Arthur S. Leonard offers this striking analysis of what the latest development at the high court means:

The Supreme Court’s December 19 denial of Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi’s motion seeking an extension of a stay put in place by the district court that struck down that state’s ban on same-sex marriages was issued with no explanation. The signal it sends, however, seems clear. There is a majority on the Supreme Court to strike down state bans on same-sex marriage.

That is the only explanation for the high court’s ruling that makes sense, and the story of the past year tells why.

Almost exactly 12 months ago, the US District Court in Utah struck down that state’s gay marriage ban, and the trial judge refused to stay his decision pending appeal. The decision relied heavily on the Supreme Court’s June 2013 ruling that nixed provisions of the federal Defense of Marriage Act prohibiting the federal government from recognizing same-sex marriages validly contracted under state law.

Even as the State of Utah scrambled to seek a stay from the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, same-sex couples began marrying there. The 10th Circuit quickly issued its own refusal to stay the decision, and Utah turned to the Supreme Court for relief. Meanwhile, hundreds of same-sex couples from Utah and neighboring states were getting married. By the time the Supreme Court issued a stay on January 6, 2014, more than 1,300 couples had married.

That stay –– another decision the high court issued without explanation –– nevertheless sent a message to lower federal courts. Although there were a few gaps along the way during which same-sex couples were able to marry briefly in several states, on the whole pro-marriage equality decisions were stayed pending review unless state governors decided not to appeal them –– as in Oregon and Pennsylvania.

Then the circuit courts of appeals started weighing in, with three circuits ruling for marriage equality over the summer and the states affected responding by filing petitions for Supreme Court review. On October 6, the high court denied petitions to review the pro-marriage equality rulings from the Fourth, Seventh, and 10th Circuits, which lifted stays in place in states in all three circuits. The following day, the Ninth Circuit ruled for marriage equality in cases from Nevada and Idaho.

Because the Supreme Court would not hear appeals of pro-equality rulings from any of these four circuits, other states under their jurisdictions were also bound by the precedent established and, in snowballing fashion, district courts quickly handed down marriage equality orders in each of them. The high court refused stays in every case where one of those states sought to delay the mandate facing them. In the most recent of those denials, Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas noted their disagreement with the court’s action –– the only explicit insight offered in orders otherwise unaccompanied by any explanation. Other justices may agree with those two but not be saying so given that no written opinion was issued, but it’s clear Scalia and Thomas were not in the majority.

By the time the high court considered Florida’s request for an extension of its stay, the number of marriage equality states had grown to 35.

Florida’s ban on same-sex marriage has been struck down by several state trial courts as well as a federal district court, and in each case Bondi filed appeals. US District Judge Robert Hinkle, who ruled in August, gave the state a temporary stay, mainly to see how the Supreme Court would handle the pending appeals of pro-marriage equality circuit court rulings. When the high court in early October declined to take up any of those appeals, he extended his stay through January 5 to give Florida time to seek a further stay at the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals or at the Supreme Court. After the 11th Circuit turned Bondi down, the high court followed suit, the first time it ever affirmatively allowed a same-sex marriage order to go into effect within a circuit whose court of appeals had not yet spoken on the merits.

Florida will become, then, the 36th state with marriage equality, with marriages also happening in St. Louis County, Missouri (which is in the Eighth Circuit), where no stay has yet been issued in a ruling there.

Petitions for review are pending at the Supreme Court from a ruling by the Sixth Circuit, the first court of appeals in the past year to reject marriage equality claims –– after plaintiff victories in district courts in Ohio, Michigan, Tennessee, and Kentucky. A petition is also pending from an adverse trial court ruling in Louisiana. It seems clear that the Supreme Court will grant review in one or more of the pending appeals, even as the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, on January 9, hears oral arguments in several marriage equality cases –– after wins in Texas and Mississippi and the Louisiana loss.

The Supreme Court’s action in the Florida case makes clear that at least five justices were comfortable with the idea of marriage equality going into effect there without an appellate ruling on the merits, which seems to me a very clear signal of the ultimate outcome of this issue at the high court. That outcome was predicted by Scalia in his harsh dissent from the court’s DOMA ruling last year. He said that the court’s ruling told plaintiffs what to argue and told lower courts how to fashion decisions in favor of same-sex marriage. Scalia’s comments, in fact –– along with similar observations penned as early as his 2003 dissent in the Texas sodomy case –– have been cited over and over again by lower federal courts ruling in favor of same-sex marriage plaintiffs.

A nationwide marriage equality victory now appears overwhelmingly likely at the Supreme Court. The only questions remaining are when the court will decide and which constitutional theories it will embrace. Some lower courts have relied on due process arguments based in the fundamental right to marry, others have ruled on equal protection grounds, and some on a combination of the two. The choice of theory is mainly of interest to legal scholars and pundits. The bottom line is what interests the general population –– and what that bottom line will be is increasingly apparent.

Arthur S. Leonard is a New York Law School professor and the longtime editor of Lesbian/ Gay Law Notes.