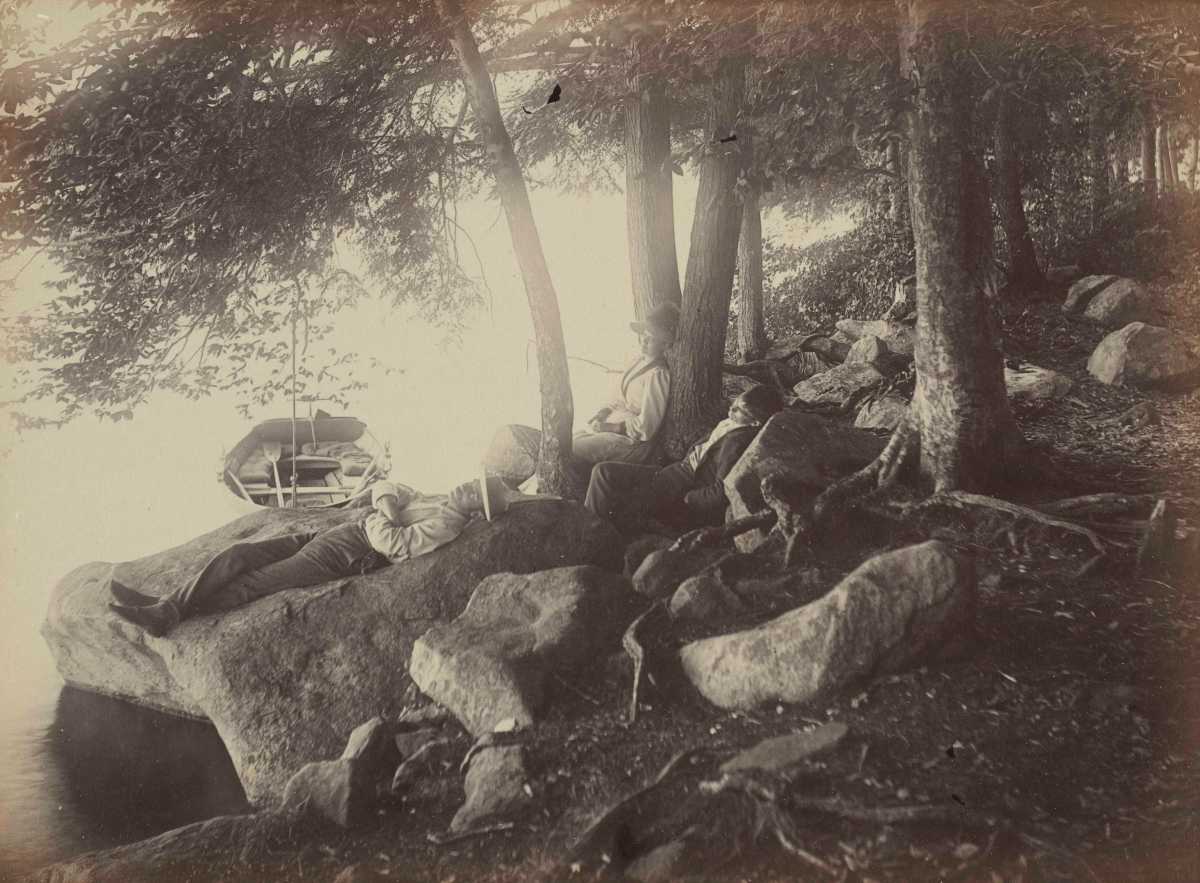

Three friends — one woman, two men, twenty-somethings, all handsomely dressed in late 19th century attire — repose themselves beneath a canopy of trees on a rocky riverside. Their rowboat, oars rested across a built-in banquette (this vessel is evidently designed for recreation, not transportation) idles on the water. The men, reclining, are lost in their own thoughts, but the woman, seated upright, casts a sidelong glance towards the photographer, a then 22-year-old Alice Austen, who in many years yet to come will be lauded, in part due to images like this one, a pioneer of American photography, one of its earliest female and known queer practitioners.

Austen, who came from an elite family and socialized in a wealthy and oftentimes whimsical circle, snapped this scene, which she titled, “Group on Petra, Lake Mahopac,” on August 9, 1888 while on a day trip to Petra Island in Putnam County, New York. The image is one of 275 photographs included in the exhibition, “The New Art: American Photography, 1839–1910” currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While the details behind Austen’s photograph — the identities of its subjects, the biography of the creator, the specific location and historical context — are documented, those of many of the show’s selections are not. In practically all cases, knowledge of the image is limited to that which is pictured — the action, dress, gaze or pose of the subject — and the approximate year of production based on its technical composition.

The mystique of inexactitude is a strong complement to works in the show by celebrated artists such as Austen, Josiah Johnson Hawes, John Moran, and Carleton E. Watkins.

The exhibition traces the chronology of photographic formats, processes, and technologies. Most visitors would be familiar with the daguerreotype, the earliest precursor of the mass-produced photograph, introduced in France in 1839 and named after its originator, Louis Daguerre. “The New Art” explores this and later techniques such as the ambrotype and tintype, forms that, while lesser known, made it increasingly possible for interested practitioners to go out, or stay in, and visually capture moments in the lived realities of Americans.

Elements in and of these photographs expose profundity in mundanity. Included, for example, is a daguerreotype, “Niagara Falls, 1853-58,” created by the commercial photographer, Platt D. Babbitt, a magnificent scene of four men dwarfed by the grandeur of the gushing falls and nature scene behind them. Babbitt, we learn, opened one of the first photo concession booths in the US, making his living by taking touristic photos for people of themselves posing beside Niagara Falls.

“Woman Wearing a Tignon” is a striking portrait of a Black woman. Made in around 1850, the identity of neither its sitter nor photographer is known. But the headwrap the woman is wearing identifies her racial and social position in Louisiana society, where at the time law mandated that free women of color keep their hair covered in public.

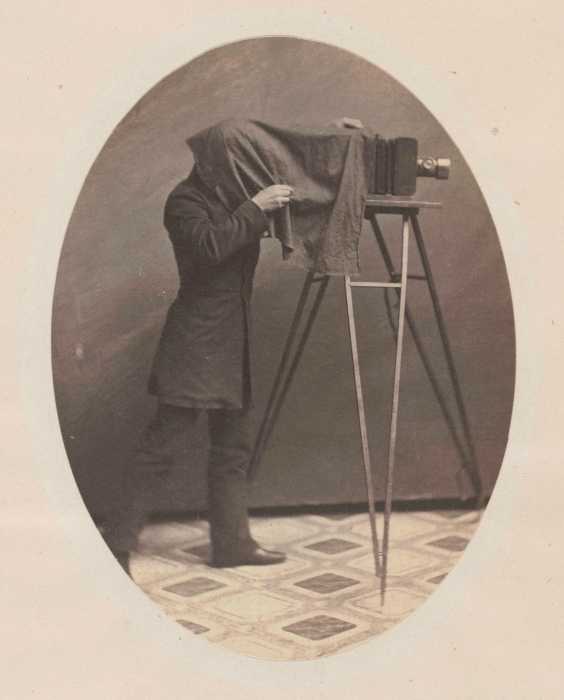

The developing professionalization of photography through the mid-19th century is explicit in the piece, “Studio Photographer at Work,” made in 1855 by an unknown creator. The stark image shows the photographer in the throes of work, his head completely covered by the heavy cloth used to blanket the camera’s viewfinder, the camera suspended to his eye level on a tripod.

This collection of photographs from the medium’s nascence in the United States shows the potential and power of the camera to bear witness.

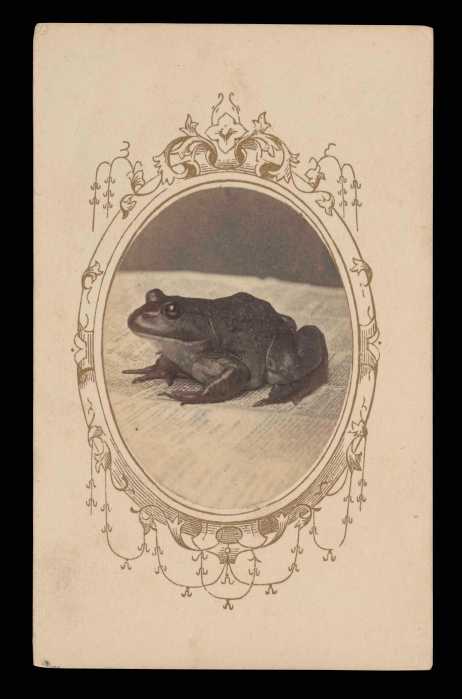

A popular photo format in the 1860s was the “carte de visite” (visiting card). It was about the size of a business card, which meant that it could fit in the palm of the average adult’s hand. Friends and family would exchange such photos for a variety of intentions.

“I’ve seen this a million times on TV, but here’s the actual photograph,” remarked an exhibition visitor when she came across, “The Scourged Back,” a small but devastating image of an African American man exposing his bare back crisscrossed by ropes of raised scars from the whippings he had endured under slavery. The sitter, named Gordon, had escaped a Mississippi plantation and taken refuge in a Union Army camp in nearby Baton Rouge, Louisiana. There, historians say, he was photographed by Wiliam D. McPherson and J. Oliver, a duo of photographers who accompanied Union soldiers around on their deployments, documenting the Civil War as it was being fought. The “Scourged Back” became widely distributed as a horrifying “carte de visite” to spread the argument for abolitionism.

“The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910” | Metropolitan Museum of Art | Until July 20, 2025