Louis Bayard, picking up from Dickens, renders a grownup Tiny Tim

It is a daunting and daring task to pick up where another author has left off and try to elaborate on an already chronicled world and the characters who inhabit it. Consider the fate of “Scarlett,” Alexandra Ripley’s sequel to the classic American novel “Gone With The Wind.” Even though the estate of Margaret Mitchell granted Ripley permission to write “Scarlett,” and the book was a commercial success, it is also, nonetheless, considered a literary failure. This is not because Ripley is a bad writer, but because of the nearly impossible task of taking “Gone With The Wind”’s iconic, beloved characters and expanding on their lives and in the process, for better or worse, tampering with people’s heartfelt attachments to what some consider to be the greatest love story ever told.

Ripley and Mitchell hail from different eras with completely different writing styles. I don’t believe Ripley’s intent was to re-create the cultural settings created by her predecessor or to imitate Mitchell’s writing style, but instead to interpose her personal interpretation of the first novel’s characters by standing on Mitchell’s shoulders, so to speak.

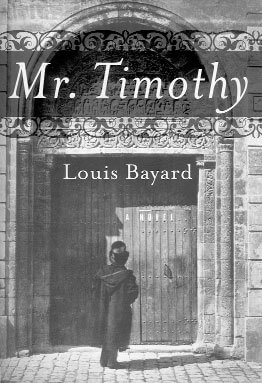

Standing on the shoulders of another literary giant––in this case, none other than Charles Dickens––is Louis Bayard, whose new novel, “Mr. Timothy,” is inspired by Dickens’ ghostly Christmas tale. Mr. Timothy doesn’t pick up where ‘A Christmas Carol’ ends,” but it has the same characters and expands on them skillfully.

Tiny Tim Cratchit, who melted the heart of the miserly Ebeneezer Scrooge in Dickens’s classic, “A Christmas Carol,” is now 23 years old and “not so tiny any more. Nearly five-eight…” Gone are the crutches and the iron brace he once had, leaving in his gait “not a limp but a lilt.” The description is the first of many inferences that had my gaydar in high gear. Of course, Tim swears he isn’t “that way,” but aren’t some of us always the last to know?

Putting that aside, Bayard masterfully creates an 1860s London swirling with drunken sea captains, smart-talking, dispossessed street urchins, ghostly visitations, and rolling brown fogs that bite off the tops of buildings. Like Dickens, Bayard takes his time to tell his story, invests more than adequate description in his characters, pays attention to minute detail, and successfully transports the reader into a London underworld that can only be revealed through the author’s telling. Bayard’s extensive research manifests itself in the sublime and he has pulled off quite an imaginative feat.

Timothy, having dropped the more familiar Tim, lives in a whorehouse teaching Mrs. Sharpe, the landlady, how to read in lieu of paying rent. He has just buried his father, is estranged from “Uncle N,” ruminates on his sickly past, and faces an unknown future with much trepidation. In today’s terms, he’d be considered clinically depressed. He’s so uninspired by life that he can’t get an erection even by his own hand.

“I might as well be making sausage,” he claims.

To give his directionless life some purpose, Tim, with the help of Colin the Melodius, a fast-talking ten-year-old homeless street urchin, takes on the valiant effort of rescuing the illusive Philomena, a twelve-year-old girl he first sees in the alley from his bedroom window, from the clutches of the evil Lord Griffyn.

Bayard has filled his story with lively, colorful, intelligent characters that aid Timothy in his quest to keep Philomena safe. There are plot twists and turns, some of which are a bit predictable, believable characters, and intriguing circumstances to keep one involved in the story’s unfolding, but at times Bayard stretches the narrative beyond an ability to suspend disbelief.

“Mr. Timothy” is an adult-themed novel about child enslavement, murder, kidnapping, embezzlement, and prostitution. However, there is a damsel-in-distress chivalrous undertaking that undermines the intelligence of the writing. Young adults might better appreciate this novel, I considered, but just as I was coming to that conclusion, Bayard, to his credit, succeeded in getting me fully involved in his characters. I continue reading, much to my amusement.

Neither the characters nor the book’s events are shallow or uninteresting. There are Timothy’s ruminations about his future prospects, letters to his dead father expressing his disappointments in their relationship, and the dredging of the Thames in the hopes of finding treasures in the pockets of dead bodies. Bayard seems capable of writing about the deeper nuances of father-son relationships as well as on the fragility and randomness of life, especially when juxtaposed by life-threatening situations.

“Mr. Timothy” is an entertaining, creative novel, in large part a character study with a somewhat interesting plot line and a happy Christmas Day ending. ‘Tis the season.