Leona Lewis in the revival of “Cats,” now at the Neil Simon Theatre. | MATTHEW MURPHY

As Gus the theater cat sings in the splendid revival of “Cats” now back on Broadway, “The theater is certainly not what it was.” Aging Gus’ glory days were a highpoint in art, quite lost in all the modernity of a world that, not incidentally, has passed him by.

When he wrote these words, T.S. Eliot was being satirical. Yet in the case of “Cats,” it’s completely true. When “Cats” first arrived in 1982, the virtually plot-free, dance-heavy spectacle was relatively new, but it changed Broadway and paved the way for the now-common jukebox musical. More significantly, Gillian Lynne’s choreography transformed dance on Broadway in a way not seen since Agnes de Mille integrated dance into storytelling in “Oklahoma.”

This little foray into theater history is relevant because the new production of “Cats” enters a culture where mass market entertainment is less tied to linear narrative, and dance is more mainstream than ever before thanks to successful TV shows that put dance on a par with other competitive sports and, not incidentally, made it acceptable for boys in ways that it previously was not.

Aerial felines and warring Trojans create two exciting — and very different — evenings

In other words, the time seems ideal for “Cats” to come back to Broadway. It arrives looking fresh and exciting with an exuberance and precision that are dazzling. The cast is fantastic and includes stars of the above-mentioned TV shows, a pop star, and more traditional Broadway performers.

The score, largely settings of poems from T.S. Eliot about cats, is still every bit as infectious and tuneful as it always was. You’d think after decades the songs wouldn’t get stuck in your head for days again. But you’d be wrong. The costumes by John Napier are appropriately feline, and his sets litter the stage with oversized rubbish that the cats can slink through and around.

Yet what really transforms this production is Andy Blankenbuehler’s choreography. Based on Lynne’s original work, Blankenbuehler has amped up the athleticism and offers a synthesis of styles and techniques that is thrilling. The result is immediate and contemporary, and suggests that a simple museum-quality reproduction of the original wouldn’t have worked.

Among the excellent cast, Tyler Hanes as Rum Tum Tugger, Andy Huntington Jones as Munkustrap, Ricky Ubeda as Mr. Mistoffelees, Eloise Kropp as Jennyanydots, and Georgina Pazcoguin as Victoria the White Cat are all standouts. British pop star Leona Lewis as Grizabella has the potentially daunting task of making this iconic role her own, and she does. Grizabella doesn’t really have much to do, other than sing the most famous song from the show, “Memory.” In the first act, we get a taste of it, as Grizabella appears for the first time. In the second, though, she gives us the full-throated version. What’s remarkable about Lewis is that although she has the pipes to do it, she doesn’t go all diva on it; she inhabits it. I’ve never really been a fan of “Memory,” but in Lewis’ beautifully rendered performance, the nuances of character are present in ways I’ve never heard before, and, for the first time ever, the song brought tears to my eyes.

If theater is to remain vibrant, it can never be “what it was.” It must accommodate contemporary tastes while pushing beyond them to entertain and astonish. No one could be more surprised than I that the current instrument for this dynamism is a revival of “Cats.”

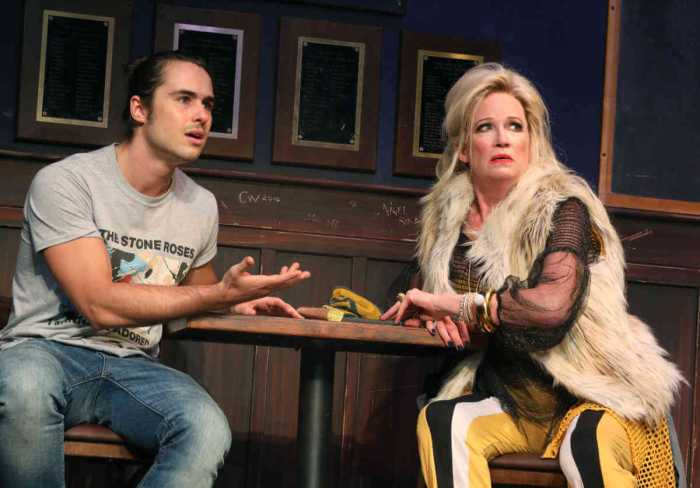

Corey Stoll and Alex Breaux in the Shakespeare in the Park production of “Troilus and Cressida.” | JOAN MARCUS

I have always been fascinated by “Troilus and Cressida” and its awkward, hard-to-define genre. Neither history nor comedy nor tragedy, the play has elements of all three and swings widely back and forth between them. Jaundiced views of love, politics, heroism, and war give the play a dark edge, even when juxtaposed against lyrical poetry about passion and faith. It’s as if Shakespeare is both celebrating and satirizing these concepts, which as challenging as that might be on the page could be daunting in production. That’s probably one of the reasons the play is so rarely produced.

But as Shakespeare has young Henry V says of “sporting holidays,” “When they seldom come/ they wished for come,” and Daniel Sullivan’s recent gripping production at Central Park’s Delacorte Theater was pretty much everything one could wish for from this play.

The play begins well into the war between the Greeks and Trojans, touched off by the abduction of Helen from Greece. Prompted by ego and ginned-up conflict, the war has gone back and forth with tremendous loss of life. Whether the war is even worth fighting is an issue that comes up early on — subdued by cries of nationalism and honor. Sound familiar? Sullivan aptly gives the play a contemporary setting. It might be the Green Zone in Baghdad. As the armies clash over honor, Troilus and Cressida fall in love, brought together by Cressida’s uncle Pandarus, and pledge themselves to one another — at least physically. Unlike “Romeo and Juliet,” there is no talk of marriage in the play.

Cressida is ultimately given as ransom to the Greeks and in her bid to survive what is essentially a gang rape, appears inconstant to Troilus. Meanwhile, the great Achilles has forsworn fighting as a promise to his Trojan fiancée Polyxena and instead lounges with his male lover Patroclus, a move that to the other Greeks weakens him. To move him back to battle, the manipulative Ulysses shoots Patroclus and blames the Trojans. The lies, reversals, and gamesmanship pile up as the blood flows, hearts are broken, and the pointlessness of love and war reverberates through it all. The play, in fact, has no real resolution other than the death of the Trojan hero Hector, King Priam’s son and Troilus’ brother. Sullivan’s messy and uncertain ending seemed perfect for our unstable and our irresolute political landscape.

Sullivan’s keen direction kept everything wonderfully clear, and his cast was up to the physical and emotional demands of the roles. Corey Stoll was perfectly unsettling as the nefarious Ulysses. Alex Breaux was wonderfully dim and aggressive as Ajax, the man sent to fight Hector when Achilles bows out. Louis Cancelmi was outstanding as Achilles, and Andrew Burnap was passionate and youthful as Troilus, the better to be destroyed through disillusionment. Bill Heck was simply fantastic as the heroic Hector, and the entire company sent chills up the spine in the climactic gun battles. John Glover bookended the play as the prologue and Pandarus, there playing a man wracked with disease, to the point of lesions on his chest. He was the perfect reflection of the play’s grim and existential themes.

Taking on a difficult story that is cynical and upsetting, the Public Theater delivered a rewarding and historic production that was surprisingly timely, exciting, and bold.

CATS | Neil Simon Theatre, 250 W. 52nd St. | Mon.-Tue., Thu. at 7 p.m.; Wed. at 7:30 p.m.; Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat. at 2 p.m. | $59-$149 at ticketmaster.com or 800-745-3000 | Two hrs., 15 mins., with intermission