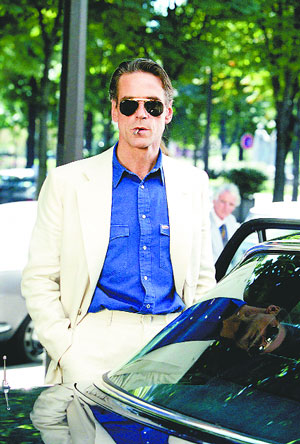

Jeremy Irons makes an offer Maria Callas can’t refuse—or can she?

“Oh God. You’re not one of those ghastly Callas queens, are you?” intones Jeremy Irons in his latest film, “Callas Forever,” in that wonderfully grandiloquent, gravelly sneering tone that only he can deliver.

The irony is that his character, 50-year-old concert promoter Larry Kelly, is actually a die-hard Callas queen himself and, in fact, was the chief force behind the legendary diva’s tours during the heyday of her career.

This tender homage of a film describes an imaginary chapter near the end of Maria Callas’ life, sprung wholly from the heart of illustrious filmmaker Franco Zeffirelli, who was a dear friend of the opera superstar.

You don’t have to be a Callas queen—or a Jeremy Irons queen, for that matter—to delight in “Callas Forever.”

Indeed, one of the film’s pleasures—and there are many—is the surprise awakening of the dormant Callas queen in all of us.

The British-born actor is working overtime these days—he recently shot “Merchant of Venice,” “Mathilde” and “Kingdom of Heaven.” And “Being Julia” is still in movie houses. He telephoned from Venice, sounding a tad exhausted, where he’s shooting the film “Cassanova,” to speak with Gay City News.

“I was very keen to work with Franco because I’ve known him personally for years and I knew this was a picture close to his heart,” explained Irons. “It’s great working with a director who is passionate about his subject. Besides, I knew he wasn’t getting any younger.”

The plot is simple enough. The year is 1977 and a moribund Callas (Fanny Ardant, who also played the diva onstage in “Master Class”), in mourning for her voice, has put herself out to pasture, sequestered in her musty Paris apartment, to pop pills and watch old tapes of her past operatic feats. Very Norma Desmond.

The devilishly smarmy Kelly, a bit long in the tooth—and the ponytail as well—convinces the recluse to reclaim her past glory by staging her best operas on video, and dubbing over her now-derelict voice with recordings from when she was in her prime. A triumphant comeback, to be sure.

And yet, Callas grapples with the Faustian ramifications of the deal—is it honest?

Irons was thrilled to be reunited with Ardant, whom he’d co-starred with twice before.

“It was a great help that we knew each other well because that’s the relationship between Larry and Callas,” said Irons. “We were running before we started, so to speak.”

There’s also a subplot about Kelly’s budding romance with a young artist cutie, Michael (Jay Rodan), who happens to be hearing-impaired yet magnificently captures the sound, and soul, of Callas’ music on canvas.

The incomparable Joan Plowwright (the saucy matriarch in “Tea with Mussolini,” also directed by Zeffirelli) stars as a wise journalist who serves as an emotional anchor to the lunatics swirling around her.

Crafting a fictional story about a cultural icon who really existed, and staying true to subject, was no easy task. Yet Irons believes Zeffirelli succeeded.

“What transpires in the movie never happened in life, but it nearly happened,” explained Irons. “Franco always regretted it never came together. I think the film tells as much about him as about Callas. He was writing a story about what creativity is, what genius is, and how it impacts those lucky enough to be touched by it.”

Since in real life Irons was far from a Callas queen, he had to conduct research to better empathize with Larry, who is loosely based on Zeffirelli.

“All I had to do was listen to Franco gush about Maria, to watch his adoration, to realize where Larry was coming from,” Irons said. “I never met Maria, nor even saw her onstage, I’m sad to say.”

While his filmography lists dozens of films, this is the first gay role for Irons, unless you count Rene in “M. Butterfly,” who was in love with a woman who turned out to be a man. But, as Irons dryly put it, “That’s a slightly different kettle of fish.”

“I don’t really believe that gender makes much difference when it comes to love, so I didn’t have to research Larry’s gay side,” explained Irons. “Obviously, I have gay friends. But if you love somebody, it doesn’t make a difference if it’s a man or a woman. Larry loved a person who just happened to be a man.”

Irons serves up a refreshing portrayal of a gay man free from swishy stereotypes—well, except for the whole Callas-worship thing. When asked if he resisted any urge to camp it up, he seemed mystified by the question.

“I’m not sure that stereotype is valid,” he insisted. “I know a lot of people whose sexuality I’m not sure about. They don’t give out particularly strong signals. Of course, there are some gay people who do, just like there are heterosexuals, men or women, who give out strong signals about their sexual orientation. But that comes from a place of insecurity. There’s no reason to flaunt your sexuality to the world.”

“I’ve never enjoyed stereotypes,” Irons continued. “I try to avoid that kind of writing. As a people I think we are infinitely more multi-layered, more interesting.”

With his long, stringy locks, garish jewelry, and ill-fitting leather jacket, Larry is a departure from many of Irons’ characters, who exude impeccable style and panache. And he’s certainly quite a contrast to the cultivated Callas, decked out in flawless Chanel. How ironic that Irons’ first gay character is a bit of a schlub in need of a “Queer-Eye”-style makeover.

It’s more than simply bad taste, according to Irons.

“I felt Larry was harking back to his youth with that pony tail,” he speculated. “Part of his desire to get Maria up and running again was to turn the clock back to when he was younger, managing a singer with a great voice. It’s Maria who points out that you can’t—time passes and you change. He has no clue that his appearance is far from hip.”

Irons is a master of delivering the knockout one-liner, such as that “ghastly Callas queen” quip, yet he refuses to take full credit for zingers.

“Those lines reverberate when the writer, director, actor and situation coalesce,” he said. “As an actor you need the timing to make a line work, but the director has to give it space. I helped by delivering it. I threw a good dart, so to speak.”

But Irons acknowledged that it’s not easy to predict which lines will resonate.

“Sometimes you see a line in a script that reads very well but it doesn’t play well, and vice versa,” he explained. “That’s all part of the alchemy of filmmaking.”

In the course of his career, Irons admitted, he chose films he knew were mediocre but enabled him to pay some bills.

“As a general rule in our business, the less meritorious the film, the more it pays you,” he said. “I’ve tried to find a balance of doing movies that appeal to me while still earning enough to live.”

“I’m more interested in practicing my craft than making films per se,” Irons continued. “Filming is actually quite a protracted, boring process. There’s a lot of waiting around and a lot of time spent away from those you love. So unless you’re passionate about the role you’re playing, and the story you’re telling, it’s doubly hard.”

When asked about divas in Hollywood today, Irons was adamant, pronouncing the age of the Callas-caliber diva long gone.

“I have my feet planted firmly on the ground,” he said. Then, after a pause, he added, “I wish I had a bit of diva in me, in a way.