Photographer employs darkroom techniques to paint with light

In the 19th century, not long after paper-based photography began to capture a widespread audience, some of the first faked images to be foisted on the gullible public purported to show the human spirit leaving the body of a dying woman, captured and made visible for all to see by that instrument of truth and science––the camera.

The idea that the all-seeing eye of the camera can reveal the unseen still lingers. Photographer Robert Flynt, at a transitional point in mid-career, has daringly tapped the power of those “spirit images.” Flynt is well known for a sensual body of work taken over the last ten years of dancers photographed underwater, the images layered with appropriations from sources as far flung as Renaissance star charts and menswear catalogues.

In this age of professional photo labs and computer digitization, Flynt is also among the last alchemists to do all of his own color printing, masterfully manipulating the washes and baths of development chemistry. His water-soaked subjects and floating images were presented by the liquid means of making an actual photograph––a rather neat conceptual package. With this current group of work, it is as if he has come onto dry land crackling with static electricity.

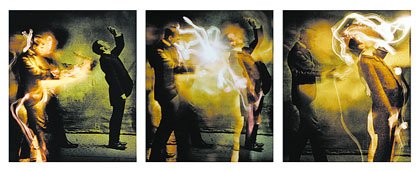

Flynt continues the use of borrowed imagery, this time employing turn of the century shots of men being hypnotized or entranced, medically measured externally with tapes and calipers or internally inspected using bodily manipulation, adjustments or palpitation. The layering mix is here altered by means of a popular performance art presentation method––the images now on slides are blown up and projected onto his dancer/models. In photographing this projected light, Flynt lets the vital physical bodies and projected images come together just off-register, slightly out-of-sync, creating a faux blurring of motion.

This already lively combination of techniques is pushed still further with the use of a third revived method––long exposures and penlights. Famously used in the 1950s by Picasso, the photographic effect is of drawing with light in space. In combination, this very painterly, gestural act yields a deeper fruit––the effect of touch; thought made visible; the spirit body charged with life.

Flynt brings together rather compelling photographic myths, but the truth of the matter is that they are all different kinds of light brought together by the means of their recording––photography––literally a record of light, again a neat conceptual package.