Met displays a bounty of riches from the Sacred Maya Kings

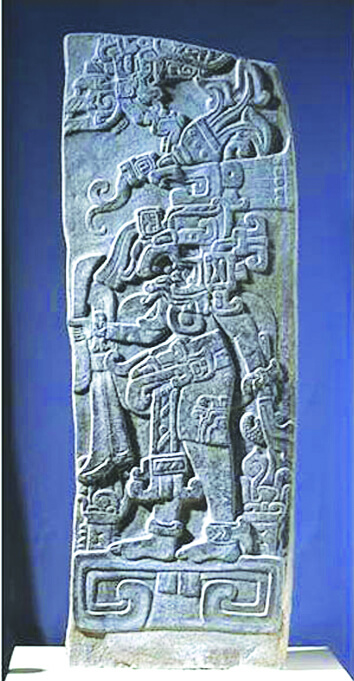

<<Commemorative Monument (Stela 11), 200–50 B.C. Guatemala, Kaminaljuyu; granite, 76 x 26 3/4 x 7 1/8 in. (Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala City )

The recent discovery of a Manhattan oven used in the 1880s to bake Thomas’ English Muffins shows how detached we are from even relatively recent history. It makes the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition, “Treasures of Sacred Maya Kings,” all the more impressive—for the bounty of wealth and the resulting artifacts produced by the Maya in a largely cohesive aesthetic, and for the trove of information they were able to embed in—and scholars have been able to extract from—these fascinating relics, which date primarily from 200 BC to 600 AD.

The organizing venue, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, originally had a more thematically complex title for the exhibition— “Lords of Creation: The Origins of Sacred Maya Kingship.” The 150-item exhibition is not overwhelming in scope, nor does it contain any overly large items. Many functional objects—vessels, mirrors—sit alongside the ritual gear and kingly accoutrements. Some of the most magnificent objects are diminutive—a half-dollar sized mask pendant of electric green jade, a “trumpet” made of a carved conch shell, a jade pendant depicting a carved seated lord on one side and dozens of delicate glyphs on the back. Because of their human scale, it is not difficult to imagine wearing or using many of the items, making it possible to relate to the nobility who actually did use them.

There are exceptions, of course, such as the “perforator,” a conical dagger (actually of earlier Olmec origin, between 900-400 BC), whose use on flesh is best left to the imagination. In addition, a number of delicate Mayan carvings were made on bone fragments from jaguars, humans, and peccaries, combining the ritual/psychological aspect with a parsimonious streak.

The exhibition is divided into prosaically denoted sections, such as “Origins,” “The Cosmos and the King,” “Religious Duties of the King,” “Personal Instruments of Power,” “Writing,” and “Feasting.” A key early work, and one of the larger items on view, the “Kaminaljuyu Stela 11” (200-50 BC) unfortunately is placed at the start of the exhibition, when it rightly could have closed the show with a bang. Its placement builds unmet expectations for objects of similar scale and execution. This isn’t meant to denigrate the rest of the show, which contained some gems, but stelae, packed with representational and symbolic imagery, and glyphs, carved in stone, and often marking special occasions such as the ascension of a king, carry special meaning. Meant to last, they function as sort of time capsules, packed with imagery, symbols, and text.

The Maya were highly skilled at converting a utilitarian object, such as the vessel, into clever and often lighthearted interpretations of the natural world that surrounded them. One lid takes the form of a turtle carapace, elegantly domed, segments lightly incised. A curled-up deer’s stomach forms a vessel’s bowl. The handles of urn tops, or the vessel bodies themselves, depict serpents, birds, dogs, squash, or figures of nobility. Such plastic pieces allowed for more realistic expressionism than two-dimensional renderings, which as yet lacked the benefit of perspective.

One of the most resplendent items in the exhibition is a jade funerary mask (200-600 AD), composed of smaller pieces of jadeite fitted together in a mosaic. The artist went to great lengths to inject notes of realism, beveling the planes of the face and shaping the eyecups. Wisps of smoke emanate from the mask’s mouth, representing the passing of breath or spirit. A similar pieced-together process was used to jigsaw hematite chips into a crude mirror.

The exhibition conveys essential knowledge about Mayan nobility and social structure—maize was the highly lucrative and worshipped staple, kings interceded between humans and gods and dressed in elaborate costumes replete with symbolic and functional embellishments, and they liked chocolate. To a 21st century chocolate-loving denizen of New York City, the scope and achievement of the Maya civilization’s power is daunting. Geographically, many urban centers spread over Central America, with trade enabling the exchange of goods and ideas. From the magnificent and widespread archeological remains and the plethora of relics such as the ones that comprise this show, it is apparent that the Maya sustained vast amounts of wealth and actively cultivated art and culture, the detritus of wealth.

And yet the artistic styles they developed seem as much at the service of function and ritual as vanity. They vary from wispy and elegantly florid (the exciting, recently uncovered San Bartolo murals, ca. 100 AD, represented in a photo montage) to cartoonish (“Censer Lid with Yax K’uk’ Mo’,” 600-700 AD), but the consistency is striking, particularly when it involved glyph writing, which graphically eliminated the use of negative space, creating a busy visual quality—a trait reflected in many of the Maya’s murals and carvings. This could reflect the strength and longevity of a slave-based, tiered society that fostered and trained a large guild of artisans. A palette limited to geological and natural finds (minerals, gemstones, shells) and pigments they could produce from these and other local sources gives the collection an aesthetic coherence.

“Treasures of Sacred Maya Kings” offers a snapshot of the elite trappings of people who cultivated a wealthy, hierarchical civilization that lasted many centuries and compares favorably with other “advanced” cultures, even our own. Sure beats Samuel Thomas’ oven, anyway.

gaycitynews.com