Will the work of one innovator become staple viewing in the U.S.?

The release of “Millennium Mambo” by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien’s is an event. One of the masters of contemporary world cinema, Hou never had a commercial release in the U.S. despite reams of critical praise until a distributor picked up one of his films in 1999. That year’s Walter Reade retrospective proved to be a turning point for Hou’s acceptance in the U.S.

For once, an “uncommercial” director had managed to reach a fairly large audience. Perhaps his interest in carefully documenting 20th century Taiwanese history made him a tough sell. His most difficult film, “City of Sadness,” is almost incomprehensible without some background information. All eight screenings of “The Flowers Of Shanghai,” his most recent film at the time, sold out, and the whole series was quite popular.

Following that series, Wellspring released four of his films on video, although the DVDs are pretty bad transfers. Yet these films never received theatrical runs. It took two years for “Millennium Mambo” to make it to U.S. shores: its release follows the premiere of Hou’s latest film in Taiwan by a few weeks.

Set in Taipei and Japan, “Millennium Mambo” opens with a lengthy shot of Vicky (Shu Qi) walking down a corridor, her long hair bouncing behind her. A third-person narrator speaks from the year 2011 (10 years after the film is set). Vicky’s trapped in a relationship with slacker Hao-hao (Tuan Chun-hao), who practices his deejay skills, smokes heroin, steals from his dad, and does little else.

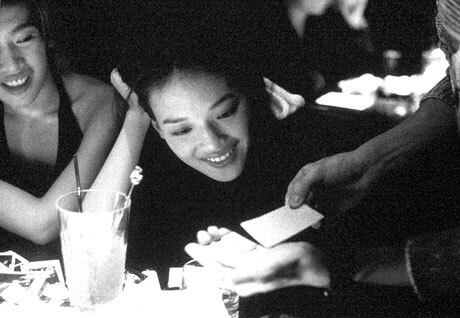

Although she recognizes that their relationship is at a dead end, Vicky keeps returning to Hao-hao. She takes a job as a bar hostess, which looks fairly close to stripping. At the club, she meets Jack (Jack Gao), a kindhearted gangster who supplants Hao-hao in her affections.

Hou’s style is distinctive and instantly recognizable. He loves long takes, letting characters walk in, out, and around the frame as the camera continues filming. These scenes sometimes appear aimless until some violent action takes place. “Millennium Mambo” uses plenty of close-ups and medium shots for the elliptical storytelling.

The time frame of “Millennium Mambo” is unclear, since Vicky recalls events before we see them happen. Her omniscience creates an odd, bittersweet tone.

It’s reassuring, because one knows that Vicky got out of a difficult situation in one piece, and strange, because we find out information about her life before she does. We’re told that Hao-hao sold his father’s Rolex before police showed up at his apartment to search for it.

“Millennium Mambo” is very fast, as well as very slow. Its speed is derived from the techno soundtrack and Hou’s constantly moving camera. Its languor comes from Hou’s rare feel for the rhythms of hanging out and doing nothing. The long takes make for an intimate understanding of Vicky and Hao-hao’s apartment. This lethargy is broken by bursts of sudden, unexpected motion.

Above all else, the film is great eye candy. Hou compensates for it’s slow pacing with a stunningly beautiful palette of blues and yellows. Shallow focus turns background lights into gorgeous blobs of color. Seen through doorways, windows become a wash of shiny blue. His use of music sometimes brings the film close to MTV territory, but its rigor prevents it from being a case of style over substance.

Nevertheless, “Millennium Mambo” never lives up to its promise. It carries too many echoes of Hou’s better films. “Goodbye, South, Goodbye” most resembles “Millennium Mambo.” Both films depict a milieu of petty criminals, break up the narrative with bursts of movement, and share a vision of youthful anomie. However, “Goodbye, South, Goodbye” critiqued an empty and corrupt society in which materialism reigns and the boundaries between legal and illegal business barely exist. Implicitly, it brought the body of work represented by Hou’s period pieces into the present, attempting to view the zeitgeist historically. The “mambo” part of “Millennium Mambo” is readily apparent; it’s anyone’s guess what it has to do with the millennium.

Perhaps the film will acquit itself better with the passage of time. Certainly, one can understand Hou’s desire to examine life in contemporary Taiwan after concentrating on nineteenth century China in “The Flowers of Shanghai.” But “Millennium Mambo” too often feels like Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai stripped of his romanticism and rendered into a cocktail of secondhand alienation and youthful angst.

This is a decidedly minor film. Still, Hou’s eye for beauty has few peers. Even one of his lesser films beats most directors’ peaks.