Brit author murdered in London before book’s publication

“Cleopatra’s Wedding Present” is that unusual book that captures the reader from the first page with its invitation to a world where most Westerners have never ventured.

Written by Robert Tewdwr Moss, a brilliant young gay writer, this memoir of journeys through Syria in the early 90s is both an insightful examination of the social complexities of Islam and a red-hot revelation of the sexual exploits of a man who allowed a place to challenge his inhibitions.

Tewdwr Moss was murdered in London the day after he finished this book, leaving this sexy, lyrical gem as his legacy. As I read the book, I was struck by the depth of insight and empathy the author had for the complexity of Middle East culture and politics. At a time when U.S. foreign policy is mired in facile and inept perceptions of Islam and the Middle East, this gay man’s vision comes as a huge relief.

Parts of present-day Syria were Mark Antony’s love gift to Cleopatra. Then and now—as we witness in this remarkable memoir—it has remained a land of desire and danger that does not reveal its secrets lightly.

In New York City I talked with Raphael Kadushin, the humanities editor at University of Wisconsin Press which published “Cleopatra’s Wedding Present,” about his commitment to this remarkable book. Kadushin has been the driving force behind the award-winning series from the University of Wisconsin Press, “Living Out, Gay and Lesbian Autobiographies.”

Tim Miller: Ever since finding a second-hand copy in London of “Cleopatra’s Wedding Present,” I have followed the cult that has built up around the book. How did you encounter this amazing book and what has pulled such a passionate urgency from you to make sure that readers in the U.S. get access to it?

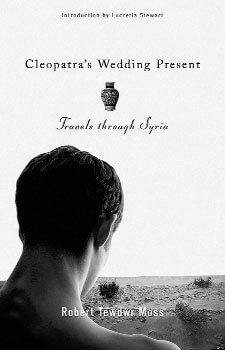

Raphael Kadushin: I was in a gay bookstore in Amsterdam and picked up a remaindered copy of the British edition, which never got much attention and never came out in the U.S. At first I thought it was soft-core porn because the British edition had a cover shot of Moss looking studly and beefcakey in a tank top, but when I read the first page I thought—my God––this is a real book. It’s so rare that you open a book these days and confront a genuine voice and a real writer so I rushed back to our flat––we were living in Amsterdam at the time—and read the book in one sitting. It’s that old cliché––I couldn’t put it down—but this was the only time, in my life, that I really could not put a book down.

TM: The book is haunted by the murder of the author in London shortly after completing the manuscript. In a book like “Cleopatra’s Wedding Present”—which is so full of sex and lurking violence—the loss of Tewdwr Moss seems a particularly ironic loss to literature. What happened and how does this inform how we read this book?

RK: There are different versions of what happened, depending on whom you talk to. But Moss was mentoring a younger man in London and there was probably something romantic going on between them. The boy broke into Moss’s apartment in Paddington, London, on August 24, 1996, the exact day after Moss had completed his final draft of “Cleopatra.” The boy and a friend bound and gagged Moss, and burglarized the apartment. Moss was found the following morning by his lodger. His feet were tied together and his hands were bound with a cord and two socks had been stuffed into his mouth.

A postmortem showed he died of asphyxiation––which means he basically choked to death on his own vomit––while he was gagged. The boys probably didn’t intend to kill him, but who knows? They were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in the British courts. To add insult to the fatal injury, the boys stole Moss’s laptop computer with the final disk of “Cleopatra” on it and that disk was never recovered, so his British agent and editor had to sit down and compare their earlier drafts and put the final book together like a big jigsaw puzzle.

So the book is really a tribute to Moss and the skill of the editors, because it reads seamlessly. The fact that he survived all those risks in Syria and then got murdered promptly upon returning to genteel England is an irony in itself, and one he would have appreciated in a very perverse way. As Lucretia Stewart says in her introduction to our American edition, Moss “should have stayed on in Syria.” The irony of all this definitely says something to all the Americans now who feel afraid to travel, because they think they’re safer at home. They’re not.

TM: It seems as if you have had a very personal investment in the book. Your series at University of Wisconsin Press “Living Out, Gay and Lesbian Autobiographies” has won a Lambda Literary Award for its major achievement in detailing queer lives. Does the untimely loss of the author’s life call forward a special degree of duty and even responsibility from you as an editor to make sure the book reaches us here in the States?

RK: Yes. Part of the “Living Out” series is about reclaiming lost voices and making sure that gay stories still get told. That’s especially crucial now because so few big commercial publishing houses still publish serious gay books and there are a lot of very strong gay writers who can no longer get published, period. What gets published and reviewed these days, instead, are the gay non-books––the homo versions of Harlequin romances, or the comedies that are written by aspiring screenplay writers, or the really bad coming out stories by illiterate 17-year-old Brett Easton Ellis impersonators, or the soft core stuff, or the picture books.

To see this crap get churned out and taken seriously and then to find a book like “Cleopatra,” sitting on a shelf, dying a premature death, with no U.S. publisher and no audience, is very frustrating. Also the fact that Moss is dead means that it’s crucial for the rest of us, who see the beauty of this work, to get it out there and demand the attention and visibility it deserves. Sometimes I feel like I’m channeling Moss. He was only 34 when he was murdered and this is his only book—the first of what clearly would have been a lifetime of good books—so it’s essential that the word gets out.

TM: In these terrible times of “shock and awe” propaganda, how does this “travel book” manage such an astute and nuanced take on Syria and Islam?

RK: Because Moss wasn’t a distant or detached traveler. He got to know every ethnic faction in Syria through his personal relations with the Syrians, and he reveals the country’s muddle through his friendships and romances. When Moss befriends Jewish merchants, German barons, Syrian cabbies, Palestinian refugees, Arab rent boys, campy florists, local characters like Baby Shoes, and the man who leads him into the desert to the site of a major ethnic massacre, and they dig up the old bones together, he isn’t a detached witness. He’s telling a purely personal adventure story and a romance that intersects with history and also reveals all the tragedies of the Middle East in a visceral way.

At one dinner party he attends the guests include one Jesuit, one Syrian Catholic, one Syrian Orthodox, one Moslem, one Armenian Christian, one Armenian Moslem, one French Catholic, one Algerian-French Moslem, and one Welsh pantheist. He also never sticks to the tourist tracks. He spends time in Damascus, but he also goes to back roads cities like Aleppo, which he describes as “this strange, dirty, collapsing town, a town with a past and no present.” He spends the night in ruined palaces, on mountaintops, in huts and tents and monasteries.

TM: It’s amazing how well the book charts the complex spaces of sex and politics. This is especially apparent in his relationship with Jihad, the Palestinian former commando. How does Tewdwr Moss manage the time bomb of human desire and the social chaos it inhabits?

RK: Like the best books, “Cleopatra” keeps changing shape, and becoming something you don’t expect. It starts out as almost a light, sarcastic travel memoir of the Englishman abroad. But then it turns deadly serious, as Moss discovers the history of ethnic atrocities and then it turns into the most bittersweet, poignant romance, as his casual sexual adventures give way to a real romance, and a love for the Palestinian man Jihad whom he first meets in a sleazy cafe in Damascus.

He first describes Jihad as a tough-looking character in his late 20s who had a long bony face, pale brown wavy hair, a missing tooth, and the air of the outsider about him. When they first sleep together on Jihad’s metal bed Moss is terrified that some loose live wires would fry them both to death in their electric bed. He only slowly sees the man’s softer side. All these elements intertwine so when Moss, after a short return to London, comes back to Syria to find Jihad, who he suddenly realizes he loves, the final search becomes an echo of all the missed connections, misunderstandings, and misplacement that make up the essence, these days, of the Middle East.

TM: It strikes me that this book could have a wide appeal—gay people, travel readers, political junkies. Who is the ideal reader for this book?

RK: The ideal reader is anyone who knows what good writing still is. It’s also a lot more erotic, funny, and entertaining than any of the cookie cutter circuit boy novels and memoirs that are clogging the book shelves now because Moss is a much truer adventurer––someone who took real unexpected risks and whose sexual marathon was much more erotic, moving, and finally romantic than the usual tale of dropping ecstasy and dating a go-go boy. This is the kind of page-turner that works on every level––as a travel memoir, an adventure story, a sexual picaresque, a romance, and a very personal exploration of the Middle East.

——————————————————————–

Tim Miller is a solo performer and the author of the books “Shirts & Skin,” and “Body Blows.” He can be reached at his website hometown.aol.com/millertale/timmiller.html. For more information about the “Living Out: Gay and Lesbian Autobiographies” series of the University of Wisconsin press, visit: wisc.edu/wisconsinpress/books/livingout.htm