Susan Sontag comes alive, in new persepctives, in Nancy D. Kates’ bio-documentary debuting on HBO on December 8. | WYATT COUNTS/COURTESY OF HBO

I love being alive.” These are the first words we hear in Nancy D. Kates’ documentary “Regarding Susan Sontag.” And as the film goes on to show in considerable detail, that’s one of the most characteristic things about the documentary’s subject — her passion for life.

Before succumbing to cancer at 71, this critic, novelist, and filmmaker (17 books, four features) had made a name for herself as a “public intellectual.” She longed to be an important novelist like Thomas Mann (to whom she wrote a fan letter when she was 15). But while her fiction is readable, it’s far from inspiring, Likewise her films “Duet For Cannibals” (1969) and “Brother Carl” (1971) — both in Swedish — are interesting but scarcely compelling as her essays were.

In her afterlife, Sontag loves a new truth

With her striking looks, complemented in later years by a Serge Diaghilev-styled streak of white in her long dark hair, Sontag took to the spotlight with great style. But she was a Diaghilev without a Nijinsky. She wanted lovers who were as complex and intellectually ambitious as she was — not acolytes to be taught. And she most certainly found them in Harriet Sohmers Zwerling, Maria Irene Fornes, Lucinda Childs, Eva Kollisch, and Nicole Stéphane, none of whom she discussed while she was alive. Her posthumously published diaries let the herd of cats out of that very large bag.

While disinclined to discuss her corporeal amours, Sontag made plain her love of the challenging and innovative in the arts (the films of Jack Smith, the musicals of Al Carmines, the novels of Carlo Emilio Gadda), all the while taking political stands that took her everywhere from New York’s anti-Vietnam war protests in the 1960s to the urban battlefields of Sarajevo in the 1990s. With great forthrightness and resolve, Sontag let us know precisely where she stood on everything , except when it came to what’s referred to ever-so politely as her “private life.”

For it wasn’t until her diaries were released that we had access to anything “on the record.” “Regarding Susan Sontag” quotes frequently from these diaries (the estimable Patricia Clarkson reading what Susan wrote), but more important it features lively interviews with several former girlfriends. The ones with Harriet Sohmers Zwerling (her first love) and Eva Kollisch (who came along a number of years later and remarks, “She was not a sensitive person”) and dancer Lucinda Childs (whose view of Sontag is similar) are especially insightful. Alas, Maria Irene Fornes has Alzheimer’s and can be said to be alive only in the technical sense. She was quite the deal among Sontag’s lovers (“Irene could have made a stone come,” Harriet Sohmers Zwerling recalls), but the most passionate of Sontag’s affairs was undoubtedly with Nicole Stéphane, the Rothschild heiress, French resistance fighter, film producer, and occasional actress (quite overwhelming in Jean-Pierre Melville’s film of Jean Cocteau’s “Les Enfants Terrible”). Stéphane produced Sontag’s striking documentary about Israel and Palestine, “Promised Lands” (1974), and helped her through her second bout with cancer — shortly after which their affair (obviously too hot not to cool down) came to an end.

What Kates’ film has been able to disclose about that affair and the rest of her romantic life is an enormous boon to understanding Sontag in general and the Sapphic world she enjoyed yet — with her adamant silence — rejected at the same time. As her last lover photographer, Annie Leibovitz (seen in archive footage as she declined to be interviewed by Kates) says, “We didn’t use those words” to describe their relationship. For to do so would render them lesbians, like anybody else. And Susan Sontag didn’t want to be like anybody else— perhaps because everyone else wanted to be her.

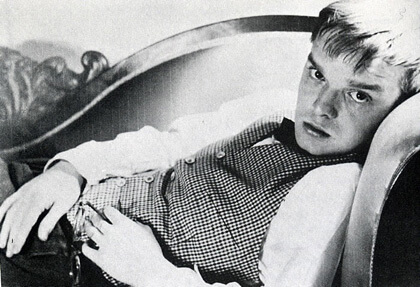

Both Susan Sontag, on the cover of her 1977 collection of short story, “I, etcetera,” and Truman Capote on the back cover of his 1948 “Other Voices, Other Rooms” (below), were pictured in a style that became iconic in the queer community. | MACMILLAN PUBLISHERS

The cover of Sontag’s 1977 short story collection “I, etcetera” is as famous as the Truman Capote picture that graced his 1948 “Other Voices, Other Rooms.” Indeed, it’s that photo’s Sapphic twin and, as “Regarding Susan Sontag” notes, wildly popularly with lesbian undergraduates.

But let’s be clear. It wasn’t that Sontag had nothing to say about gay matters — just nothing about lesbian ones. She counted Roland Barthes, Wayne Koestenbaum, Elliot Stein, and James McCourt among her closest friends, and even those ill-versed in Sontag know her essay on the cornerstone of gay culture, “Notes on Camp,” put her on the map. In other words, she’d rather be known as a Fag-Hag than a Dyke. But Kates will have none of this. And as a result, the effect of “Regarding Susan Sontag” is rather like the “Stateroom Scene” of “A Night at the Opera,” with lesbians tumbling out of the closet door Sontag had thought she’s sealed shut.

“My desire to write is connected to my homosexuality. I need the identity as a weapon to match the weapon that society has against me,” she writes in her diaries. This bespeaks a sense of militancy. Yet while very much present in other aspects of Sontag’s life, that wasn’t the case here. “I am just becoming aware of how guilty I feel being queer,” she acknowledges.

Yikes! Susan was “Desperately Seeking Susan.”

She was born Susan Rosenblatt, the daughter of Mildred (née Jacobson) and Jack Rosenblatt. He ran a fur-trading business in China, where he died of tuberculosis in 1939 when Susan was just five. After that, as her sister Judith explains, “We had a lot of uncles who were not our uncles.” Until seven year later, when her mother married US Army Captain Nathan Sontag, thus bringing about the most felicitous name-change-through-parental-remarriage since Truman Persons became Truman Capote. The Sontags moved to Sherman Oaks, California, and in an interview she gave later in life, she recalled of how one day “Mr. Sontag” (described by her as “a tall pair of pants”) discovered her on the floor of the living room reading a book and announced she’d never get a husband if all she did was read. Sontag said she burst out laughing because she couldn’t imagine wanting to marry anyone who didn’t love to read.

Truman Capote on the book jacket to his 1948 “Other Voices, Other Rooms.” | HAROLD HAMA/ RANDOM HOUSE

What’s doubly amusing is the fact that in 1950 she did marry a man precisely because of his well-read-ed-ness. Philip Rieff was her sociology instructor at the University of Chicago, “a thin, heavy-thigh-ed balding man who talked and talked… We talked for seven years.” Herbert Marcuse lived with Sontag and Rieff while writing his signature work “Eros and Civilization,” and, prior to their divorce in 1958, Sontag contributed to Rieff’s study “Freud: The Mind of the Moralist,” which would come out in 1959.

“It was not a pleasant divorce” sister Judith notes dryly, suggesting that Rieff might have thought Sontag’s lesbianism “a phase” and was shocked at discovering that that was far from the case. She’s most remindful at this point of Lauren Bacall’s character in “Young Man With a Horn,” who declares to her husband Kirk Douglas, “I’m an intellectual mountain-goat leaping from crag to crag.” That character was a lesbian like Sontag. And Rieff was to her a major crag.

The Rieff-Sontag marriage it should be noted came after she had begun an affair with Harriet Sohmers Zwerling,who in 1948 introduced her to “the gay world” in San Francisco. Was Susan a Hasbian? Not at all. Rieff was clearly her route to growing up fast — she hated being a child — while gaining access to knowledge she desired at the same time. So it was college at 15, marriage at 17, a child at 19. Rieff was “on her reading list” as it were. She had first heard about him as being “a man who was putting Freud and Marx together.” This was all-important to Sontag.

As for emotional involvement, her sister Judith says, “They acted like they were one person… How much love was involved, I can’t say.” But she gave birth to a son David — who she almost immediately handed over to relatives so she could go to Oxford, after which she rejoined Harriet Sohmers Zwerling in Paris. As Judith says, “She did what she wanted to do.” In later years, David became an exceedingly important part of the emotionally needy Sontag’s life while simultaneously serving over those years as a kind of living Get Out of Jail Free Card for a heteronormative culture that always defaults to straight.

“My habit of holding back is loyalty to my mother,” Sontag says in a quote read by Clarkson that also includes the telling disclosure, “My actions say I have not loved the truth. I do not want the truth.” Well, it all depends on which truth. Sontag was a seeker after truth overall and was exceptionally honest in her critical writing in detailing just what it was she loved about Jean-Luc Godard, admired in Simone Weil, and thrilled to in Hans-Jürgen Syberberg.

She’s unique among serious critics in changing her mind in full public view. While in early essays she saluted the aesthetic beauty of Leni Riefenstahl’s films, in her famous essay “Fascinating Fascism” she completely recanted that “art for art’s sake” position. Taking no position about lesbianism in her art puts her in a place apart in Queer Studies somewhat akin to that of Gore Vidal. Yet Vidal managed to speak out on gay issues and she didn’t as far as lesbians were concerned. For while it was noli me tangere with the girls, it was open house with the boys. Susan Sontag much preferred to be known as a Fag-Hag on the highest cultural level imaginable.

This proved helpful in many ways. Wayne Koestenbaum notes that the narrator of her first novel “The Benefactor” is a gay man and asks, “Does the author of ‘Notes on Camp’ need to come out?” The answer of course is a resounding YES! But Sontag had her image to polish, and that’s what her gays — not her lesbians — were only too happy to oblige with. It was James McCourt, for example, who counseled an upset Sontag that it was a great compliment when Esquire magazine referred to her as “the Natalie Wood of the avant-garde.” She had been under the impression that Wood was a B-movie actress, which she most certainly was not. A fortiori Natalie Wood (who mentored Mart Crowley during the writing of “The Boys in the Band”) was as big a Fag-Hag as Susan Sontag.

And then there was the matter of disease. Sontag had two initial bouts of cancer — both of which she was given scant chance of surviving. Out of them came her study “Illness as Metaphor” (1978), which became even more important when the AIDS pandemic hit and found her “going to a funeral every week.” Discovering how much her book had come to mean to the HIV-positive, she wrote “AIDS and Its Metaphors” (1988). Both of these works meant a partial recanting was in order for a passage in one of the most vivid pieces of writing she ever penned, in a 1966 essay entitled “What’s Happening in America” published in the Partisan Review: “The truth is that Mozart, Pascal, Boolean algebra, Shakespeare, parliamentary government, baroque churches, Newton, the emancipation of women, Kant, Marx and Balanchine ballets don’t redeem what this particular civilization has wrought upon the world. The white race is the cancer of human history; it is the white race and it alone — its ideologies and inventions — which eradicates autonomous civilizations wherever it spreads, which has upset the ecological balance of the planet, which now threatens the very existence of life itself. What the Mongol hordes threaten is far less frightening than the damage that Western ‘Faustian’ man, with his idealism, his magnificent art, his sense of intellectual adventure, his world-devouring energies for conquest, has already done, and further threatens to do.”

I know why having experienced cancer herself Sontag felt metaphorical use of illness was too glib. But speaking as a Black American, I can only applaud her for Speaking Truth To Power so resolutely. It’s why a Heritage Institute stooge in the clip that opens the film, shot in the wake of the 9/ 11 attacks that Sontag pointed out were not carried out for entirely irrational reasons, whines, “You’re part of the ‘Blame America First’ crowd,” to which one is sorely tempted to answer “Yes, blame America first — avoid the rush.”

In a speech she gave in 2003 about sundry political matters, Sontag declares, “Don’t take shit. Tell the bastards off.” And to her everlasting credit, she did to a large part. One can see its effect to this day as for example in a piece written for the Telegraph by one Kevin Meyers decrying her personal behavior that he witnessed: “I have never seen anything as degrading and insufferable as her conduct towards the Sarajevans… She never listened to any of them but only uttered lordly pronouncements as she held court in the Sarajevo Holiday Inn, while outside scores daily died.”

The essay is entitled “I Wish I Had Kicked Susan Sontag.” Yes she was not a perfect person. Far from it. But if I should ever get the opportunity, I’d dearly love to kick Kevin Meyers.

REGARDING SUSAN SONTAG | Directed by Nancy D. Kates | Question Why Films/ HBO Documentary Films | Premieres Dec. 8, 9 p.m. | HBO