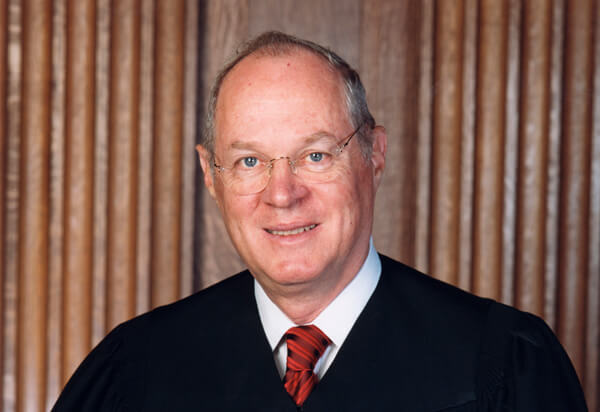

Justice Anthony Kennedy's views on marriage equality may have been key to the stay issued by the high court. | UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

On the morning of January 6, the US Supreme Court, in a brief order, issued a stay blocking enforcement of the December 20 ruling by US District Judge Robert Shelby giving same-sex couples in Utah the right to marry. The State of Utah is currently appealing Shelby’s decision at the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals.

“The application for stay presented to Justice [Sonia] Sotomayor and by her referred to the Court is granted,” the order read. “The permanent injunction issued by the United States District Court for the District of Utah… is stayed pending final disposition of the appeal by the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit.”

This said everything and, yet, at the same time left many questions unanswered. First, Sotomayor, rather than deciding the issue on her own –– as she had authority to do as the justice who handles such stay motions for the 10th Circuit –– referred Utah’s application to the full court, as most observers expected her to do. Her decision on that score really needs no explanation, given the controversial nature of the issue before her.

Responding to state’s motion referred to full court by Sotomayor, stay granted while 10th Circuit takes up case

Second, the full court granted the application, but as is its normal practice, did not provide explanation as to how the State of Utah met the criteria the court applies in this type of situation –– where on a constitutional question, the Supreme Court is asked to stay a decision when both the trial court and the court of appeals have denied the very same application.

In cases where the Supreme Court is not unanimous on a stay application, there is occasionally a dissenting opinion by one or more of the justices, which can shed some light on the discussion, if any, among the justices. Here, there is no indication of that.

As a result, one can at best only speculate about the rationale for the court’s action. In my view, had the court applied the legal standards previously employed, it would have denied Utah the stay it sought. In their January 3 memorandum opposing the state’s application, the plaintiffs made a persuasive argument that the Supreme Court typically imposes a very high burden on a party requesting a stay under such circumstances. It’s not enough to show that the state might win its appeal. It must demonstrate that the court of appeals’ rejection of its request was “demonstrably wrong.” The plaintiffs also devoted a large part of their memorandum to showing how the district court’s decision was consistent with the developing case law under the 14th Amendment, and thus likely to be upheld on appeal by the 10th Circuit.

But the high court is also influenced by realpolitik, which in my assessment is why the stay was granted. Is anybody surprised that it was this standard that governed the court’s decision?

In understanding the court’s decision, it is also worth considering a discussion that took place on January 5 at the annual meeting of the Association of American Law Schools in New York. One prominent legal scholar who spoke argued that Edie Windsor’s victory in last summer’s DOMA case did not signal a readiness by the court to embrace marriage equality as a 14th Amendment equal protection requirement imposed on the states. Even though Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion spoke a lot about the federal government’s obligation to respect the dignity of same-sex married couples by not discriminating against them in determining federal rights and obligations, this scholar emphasized that the court spoke of that dignity as something conferred by the state when it opened up marriage to same-sex couples. Kennedy’s opinion made several references to the traditional role of the state in defining marriage.

If this perspective –– drawn from a close reading of Kennedy’s decision by a legal scholar politically disposed to support marriage equality –– accurately describes the limits of his support for the issue, then perhaps the court concluded that the State of Utah had shown that its chances of prevailing on the merits are strong enough to support staying Judge Shelby’s December decision pending a final appellate ruling.

The important and immediate question the court’s order does not address is the status of the roughly 1,000 same-sex marriages licensed and performed in Utah between December 20 and January 3. Are they presumed to be valid and entitled to be treated as valid by the federal, state, and local governments during this interim period of the appeal? This is a question with significant practical implications since those couples who married by December 31 need to know which tax status they should use –– single or married –– in filing federal and state income tax returns and, possibly, estate tax returns, in the event of a spouse’s death.

Over the next several months while the 10th Circuit considers Utah’s appeal of Shelby’s ruling, questions will also arise over whether these couples will be treated as married by the federal and state governments on a host of other matters as well, including Social Security survivor benefits and Family and Medical Leave Act entitlements. Republican Governor Gary Herbert, an opponent of marriage equality, earlier advised state agencies that same-sex marriages that took place beginning on December 20 should be fully recognized on matters such as state employee spousal benefits. Whether that policy continues now that a stay has been issued needs to be clarified quickly.

The Obama administration must similarly make clear how the federal government intends to treat the same-same marriages that took place in Utah in late December and the first few days of January.

The status of those marriages in the event Shelby’s order is overturned will also be a critical question to be resolved.

Arthur S. Leonard is a professor at New York Law School and for three decades has edited Lesbian/ Gay Law Notes.